Other & Father exhibition| Interview with Mariah Garnett

Mariah Garnett (born 1980, USA) came to Belfast for the first time in 2015 for a residency at Digital Arts Studios. Now she premieres a new project in her first UK/Ireland solo exhibition, at the MAC.

Garnett’s practice borders on the periphery between experimental filmmaking and fine art installation. She has an impressive CV, having shown in LA, New York, MOMA San Francisco, and the Venice Biennale. She is represented by ltd los angeles. Creating relationships with her subjects is an important thread throughout her practice, and she has focused on iconic gay porn star Peter Berlin, transgender historical figure Catalina de Erauso, and US war veterans.

Now she has embarked on a new project entitled Other & Father looking at her relationship with her father. He lived in Belfast as a youth, but was forced to leave because of damaging footage released by the BBC in 1971. Garnett returned to Belfast to expose the impact this had on her father, and on her own life.

Mariah was kind enough to lend me her time to shed some light on the project, and her practice. You can see the show in the MAC’s Sunken Gallery, Belfast until 24th.

In the course of this project you examined your growing relationship with your father. Were you aware of the BBC footage before you started the project?

I met my dad ten years ago for the first time, but I’ve always known about him and had a relationship of sorts through letters. In the course of this project I’ve been able to spend more time with him than I ever had before, which lead to fostering a deeper relationship with him, grounded in real time spent together. It’s the best imaginable outcome of an art project. My mom told me the story of why he left Belfast and going on the news, so it was always this kind of romanticised drama in my imagination. Looking for the BBC footage was what lead me to embark on a film and to look at my relationship with my dad as a project. What I found was far less dramatic than I was expecting. I think I’d blown it up to something on the level of In The Name of the Father in my imagination, and was shocked and maybe even a little disappointed to find that the news special that forced my dad to leave Northern Ireland mostly consisted of old ladies and priests talking about what church he and his girlfriend should marry in. After spending more time in Belfast, though, I got a deeper understanding of the material and how controversial it might have been at the time.

Was it important for you that the first showing of Other & Father was in Belfast?

It turned out to be important that Other & Father premiered in Belfast. I didn’t necessarily have a premiere in mind but when the MAC approached me about doing it there, it occurred to me that it was important that it show there first, because it plays so differently in Belfast than it might any where else in the world. There is an innate understanding of the material and its stakes in Belfast that doesn’t really translate anywhere else, even in the Republic. I hope those stakes come through in some kind of subliminal way when it shows in LA (at ltd los angeles opening March 12), but in Belfast there is concrete meaning attached to every aspect of the project. For example, when my dad says in the original footage “i have a brother in a flute band”, that meant nothing to me when I first heard it. In fact, a guy in a flute band in the States would probably be considered a nerd or a wimp, whereas in Belfast, it’s the opposite. Also, I’ve come to feel a strong attachment to the city which initially stemmed from my dad’s being from there, but has really taken on a life of its own, so I’m really pleased to have been able to present it there first. There’s a long tradition of images of Belfast being exported by foreign image makers as sort of badges of courage for the people who make them, and I really didn’t want to be a part of that.

What was the relevance of your play with gender roles in this project?

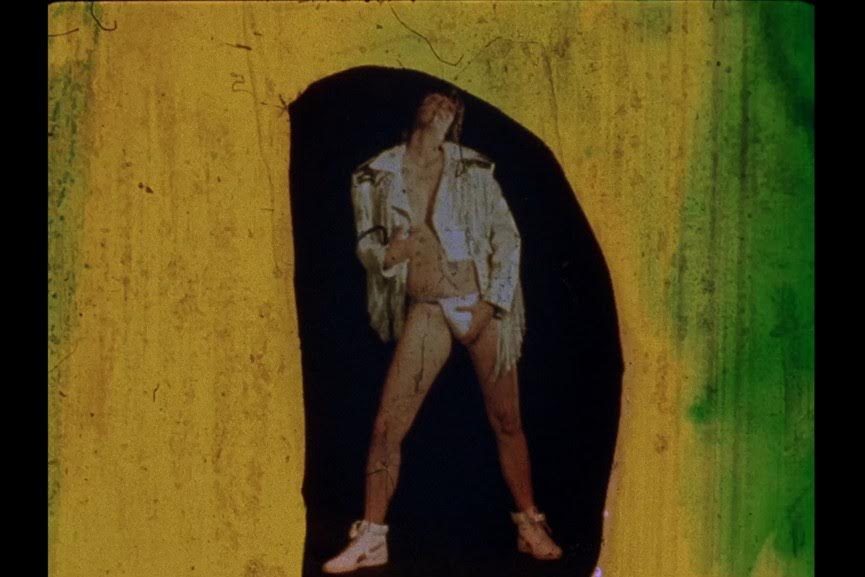

Maura, my dad’s girlfriend, is played by Robyn Reihill, a Belfast-based trans actress. I chose to play the role of my father as a way of better understanding him, and I don’t consider it drag, which is why I was seeking a trans actress to play Maura. I did want a similar gender thing to be happening with both characters because I like symmetry, but I wanted it to be as sincere an expression as my attempt to embody my father, rather than camp or drag. In daily life, I don’t actually dress much differently than my dad does now – he’s a bit of a sharper dresser than I am. So putting on the clothes is a way of embodying the “character”, who in this case is my dad. I am not particularly interested in acting – whenever I take on a role or use the strategy of impersonation to access material or subjects, it’s not exactly acting in the sense that I don’t particularly care about realism, but more of a personal quest to connect with the person or subject I’m enacting. In terms of questioning gender roles in Belfast, I think it was more of an attempt to project my own queer experience onto that situation as a way of better understanding and embodying that footage.

Your diary mentions your father painting in the other room while you stayed with him. Is he also an artist?

My dad is an artist. He’s a painter and a sculptor mostly, though he’s showed me some videos he’s made. I think he’s done a bit of everything. There isn’t a lot of similarities between what we do, but I think his being an artist has made this whole process easier because he understands what it’s like to make a work, and he’s been very generous with his story and time in general surrounding me making this.

In your interview in the MAC you speak about your films as subjective truths: your own truth. What is the role of truth within this project?

The simple answer would be that I think all truth is subjective so the pursuit of some definitive true statement will ultimately yield nothing. But I also think the pursuit of a truth is worthwhile and interesting even if in most cases you come up empty handed. In this project, truth is attacked from all angles sometimes with violent consequences – the BBC essentially fabricated a story about my dad which caused him to leave the country (which, incidentally, is the reason I’m alive today. If he’d stayed he probably never would have met my mother). So this is the first violation of Truth. But then it’s also informed by memory, both personal and collective on micro and macro scales. So much of what I’m investigating in the larger project happened so long ago that people’s memories shape the narrative, as do the events that have transpired between now and then, and the political attachments held by the people I’m talking to or looking at. Truth is hard to come by in Belfast when looking at the Troubles, not because of lies necessarily, though in an overarching systemic way lying does play into it, but more because of polarization wrought by personal experience in different corners of the city. You look one way and you think one thing is true, and then the whole picture changes when you look in the opposite direction. This is generally true everywhere, but it’s extreme in Belfast.

The subjects in your films (the war veterans, Peter Berlin, Phoebe, your father…), do they dictate the atmosphere and direction of the films?

I like to let things play out in front of the camera relatively naturally. I never want people to tell me stuff they don’t want to talk about, and I rarely even have questions prepared. Most of my interviews are staged as conversations. So in that sense my subjects do dictate the atmosphere and direction to a certain extent. I’d say most of my films are about a relationship, even if it’s brief and not super intimate (like in the case of the veterans, most of them I only met once or twice), so I guess neither of us dictates what happens in particular. In the Peter Berlin film, he told me he didn’t like looking at himself now, so we came up with the idea of not picturing him directly. Once I get in the edit, though, that’s really where the films take shape and where I exert control and direction.

Do your influences lie in art and film or elsewhere?

I have so many influences, it’s hard to choose. David Bowie, Werner Herzog, Alex Bag, but mostly and more and more, my artist friends and colleagues: Jesse Jones, Seamus Harahan in particular with regards to this project, but generally Eve Fowler, Math Bass, Celeste Dupuy-Spencer, Stanya Kahn, Ryan Trecartin, Dynasty Handbag, David Benjamin Sherry, Nicole Eisenman, Ben Rivers, Thom Andersen….I could go on but it’s always kind of evolving. And everyone I’ve ever made a film about.

Where might this project lead to next?

I don’t know if it’s important for it to become a single channel film, but I do see all of the threads I’m investigating as being related and I’m up for the challenge of incorporating them into one longer piece. Usually I work in the short form – the longest thing I’ve made is 20 minutes, and I wanted to take on something bigger when I started this. So, for now, I’m continuing to seek out people who were in the People’s Democracy, and anyone else who might remember my dad or his girlfriend from the time they were together, as well as just look at and document my own evolving experience of the city and my relationship with my dad and his history.

Make sure to get to The MAC, Belfast before 24th April 2016 to check out Other & Father, along with Niamh McCann and Helen O’Leary’s debut exhibitions in Northern Ireland.