Interview | A Geothermal Love Story with Caroline Doolin

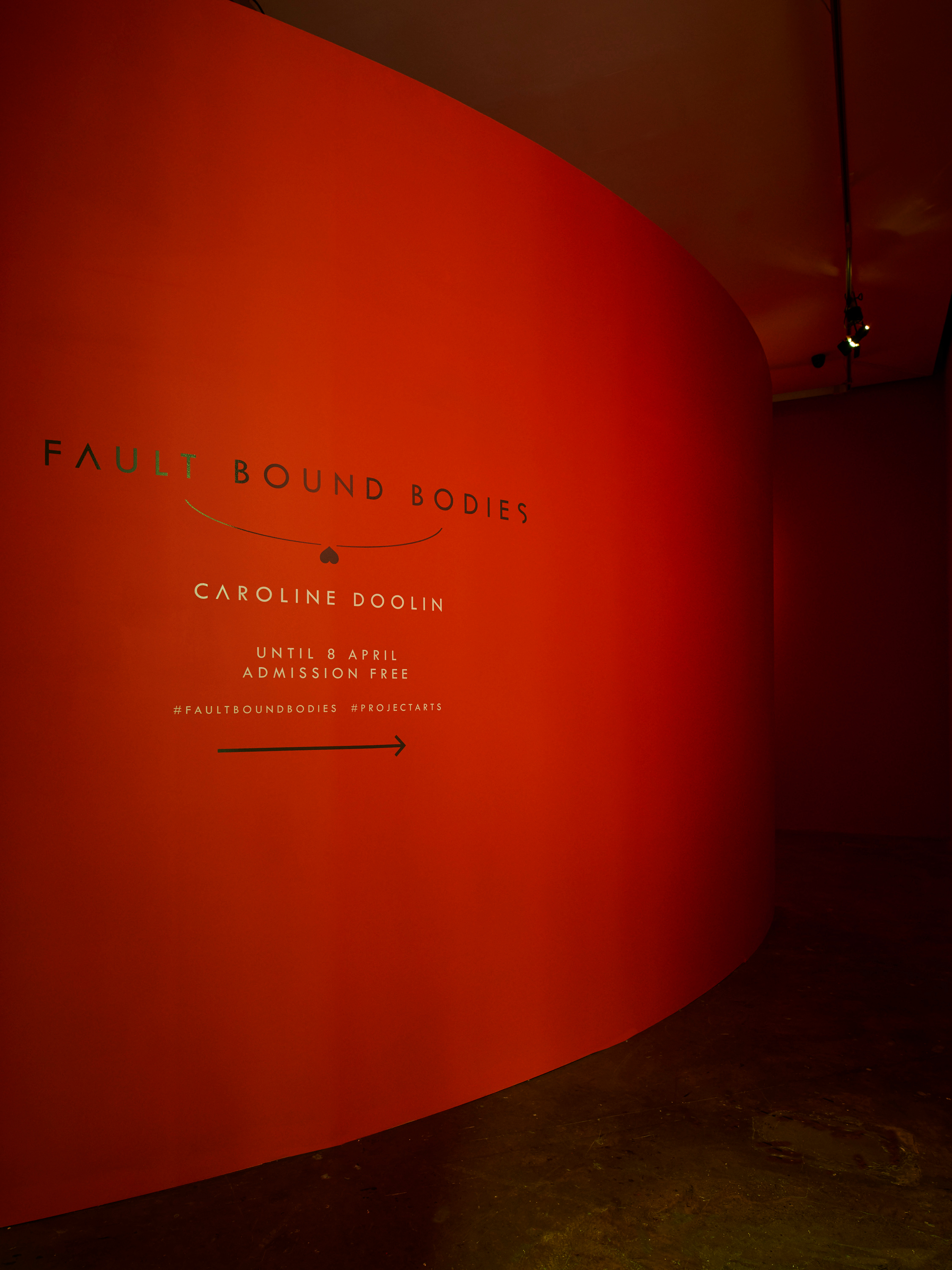

I first meet Caroline Doolin, the artist behind Fault Found Bodies standing in the dark and orange enclosed sphere that currently houses her work in Project Arts Centre. The room “takes the form of two intersecting curved balls – that structure is loosely based on a diagram of a cross section of the earth.”

Upon entering, the viewer is faced with a screen that depicts video images ranging from volcanic matter to computer generated images that look like they could belong in the landscape of the 1982 film, Tron.

The piece runs at approximately eighteen minutes, and is something of an abstract love story between a small island called Lambay, located off the coast of Dublin, and a geothermal site in Iceland.

A Geothermal Love Story

Doolin had started off wanting to interrogate what energy meant. Previous work had been about the formation of petroleum, and how it is used by human and non-human entities. Doolin had wanted to focus on the idea of energy, but didn’t find the space to explore energy within the work.

On a residency in Portrane, in Fingal, Co. Dublin, a morning walk inspired the beginning of what would eventually become Fault Found Bodies. A local man told Doolin about the energy in the rocks, and she was immediately intrigued, wanting to use that natural occurrence as a jumping-off point. “Most ideas in the work begin in a rational place.”

When Doolin wondered how to investigate that energy, it was suggested that she meditate on the rocks to tap into their psychic energy – Doolin set all cynicism aside, and attempted it, not doubting the validity of the enterprise. It didn’t quite work, however: “I needed something that was a bit more informational.”

Doolin then made a “leap of association,” after discovering the rocks would have had connections with an extinct volcano. Lambay was originally connected to America and Iceland, formed and separated by the movement of tectonic plates. Thus, an unusual love story was created: the chasm that the earth’s crust created. “It’s quite cheesy at times, and melodramatic, and intentionally so – I think you open yourself up to that ridiculousness in any relationship.”

It’s a narrative about how the same energy can manifest it in different ways: chaos, or channelled perfection, that Doolin was able to interpret in her own way, even if it may not be entirely empirical. “I’m sure scientists would be appalled.”

Caroline Doolin’s Motivational Frameworks and Latent Potential

[pullquote]We live in an age where our potential is seemingly never-ending: there is always the possibility of being the best version of ourselves.[/pullquote]

We live in an age where our potential is seemingly never-ending: there is always the possibility of being the best version of ourselves. In Fault Found Bodies, there’s potential in a variety of forms. There’s the potential of the work itself, the potential energy found in magma, and there’s the potential to be the purest version of oneself when matched with a soul mate.

Doolin would frequently find herself putting on the motivational speech podcasts of Eric Thomas, known as @etthehiphoppreacher online and sampled on ‘A Fire Needs to Burn’ by Disclosure, and became fascinated by the structures of motivational speech.

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4nsKDJlpUbA” title=”‘A Fire Needs to Burn’ ft Eric Thomas”]

“A real core reference point was this idea of motivational speaking. As a form, there’s not a lot of content. What they say isn’t that inspiring. It’s how they say it, it’s really integral.”

Linked to motivation is the ability to produce tangible results, which is bled into our relationship with nature. “It’s not enough for the planet to sustain itself, it needs to sustain itself for productivity. The less energy we have in the world, the more we seem to demand it, both in the planet and ourselves.”

Personally, I am fascinated by the distinction between mediocrity and what is considered unique: I ask Doolin about the relationship between chaos and perfection when it comes to rising above the norm. “Anything exceptional probably doesn’t come without any sort of chaos in between. I don’t think they’re at odds, I think to some degree they’re contingent on each other. If I think in planetary terms, they occur in cycles…I don’t think in terms of achievement, or where the planet might go in a system, it’s always temporal.”

Revealing and Rendering Mediated Spaces

Doolin finds herself still confused by some aspects of her own work. In the case of Fault Found Bodies, there’s a lack of clarity about the meaning of a snippet of found footage video depicting a man delivering baby sharks from dead mother on a beach. “It embodies the difficult of love in a way, and our relationship to the planet…it’s a well-intentioned and tender moment, but it’s brutal in a way…there’s no respect for the body of this animal, there’s the laughter of young girls in the background, it becomes an event.”

This lack of perfection in the work is deliberate, as it refuses to be streamlined. An example of this the 3D imagery made through coding, which was created in conjunction with two 3D animators. When the images had been created, Doolin requested the code and inserted the code into the piece “because I wanted to understand more complexly what this space is made of. I think these spaces in the video are as valid as the real world terrains I went to visit. By revealing the code, I hope they reveal the mediated nature of other spaces.”

There’s a connection between the randomness of procedural generation, and how so-called natural spaces are created through time. “I found commonalities there…It’s trying to reveal how the space is being mediated, how’s it being built on, without being the entire thing itself.”

By paying homage to landscapes of 1980s film and video games, it hopes to think about how cyborg spaces might exist within the future. “Any concept of purity is delusional in relation to nature.”

Spatial, Natural, and Manufactured Narratives

Within the work, “there are two very distinct voices.” Initially, there is a Scottish voiceover, a reference to the geologist James Hutton, also known as “the founder of modern geology.” Caroline Doolin is fascinated by the the story behind Hutton’s discoveries.

Through serendipity, Hutton was able to prove his theories about the earth’s core, having previously been accused of heresy. An excursion to Glen Tilt, and a simultaneous bottle explosion in Edinburgh, could prove theories about a molten core. “His voice shaped modern geology to a certain extent.”

As the voice deepens, it’s not a gender shift (which Doolin acknowledges it could be mistaken for), but a shift in physical position. Later, the voice sounds female, but manufactured. “It didn’t seem right to give this non-human entity a human voice…it’s partially technological, partially natural, partially human.” In this way, the voice can’t occupy a sense of naturalness, although natural rhythm is created through editing and grammar, with inflection manufactured through exclamation points.

How Caroline Doolin Refines Chaos

[pullquote]Talking to Caroline Doolin is a tangential process, as she becomes wrapped in various ideas throughout the conversation.This isn’t to say that she’s easily distracted, by any means – each new conversational path is cultivated in depth.[/pullquote]

Talking to Caroline Doolin is a tangential process, as she becomes wrapped in various ideas throughout the conversation. This isn’t to say that she’s easily distracted, by any means – each new conversational path is cultivated in depth. This trait inherent in her personality is clear in her work, through the various themes involved. However, she couldn’t possibly explore every idea she had, so I’m curious as to how she creates structure for her work.

For Doolin, something she was certain would be important from the very beginning, was the process of editing the video. “I can’t put a shape on this conversationally, so editing is a really vital tool for working through these ideas.”

The piece involved a three-month edit, with Doolin shooting throughout – until a week and half before the piece was due to be finished, in fact. Editing allows her to “think through the chaos of what just happened and the aspiration of what’s yet to come.”

The cut-off point of deadlines is just as vital, practically, to “put restraints on the potential infinite nature.” Caroline Doolin could probably explore her various ideas for years: “I think maybe it’s like browser tab mentality, one thing leads to another to another,” a feeling anyone who has ever procrastinated can recognise. Luckily, it’s the framework of being a professional artist that forces Doolin to create endings: getting into spaces, applying for funding, deadlines – everything is forcing you to stop.

This creates a dynamic that reflects Doolin’s aim “to try and utilise the things I’m actually trying to talk about without extracting myself. I want to acknowledge the insufficiency of those forms.”

By creating work that doesn’t aim to fully answer its own themes, Caroline Doolin can continue on her next path: “At the end, there’s parts opening up to the next work I want to make…there’s parts that are still a mystery to me.”

Fault Found Bodies appears in Project Arts Centre until April 8th, 2017.

Caroline Doolin appears in conversation in Project Arts Centre on April 7th, 2017. Click here for more info.