Halloween Creatures in Five Centuries of Art

The holiday we now know as Halloween has a long and somewhat complicated history, beginning as an ancient solstice ritual and transforming over several centuries before emerging as the largely commercial celebration it is today. It should be no surprise that the appearances of Halloween characters such as witches and vampires have developed as well. Let’s take a look at the representation of Halloween creatures in five works of art across five hundred years.

Young Man and Death from Book of Hour/Life of St. Margaret (Paris, Bibl. Mazarine, MS 0507, f. 113), c. 1490

Would you be surprised to find out that the zombie-like creatures shown above appeared in a medieval religious manuscript? Such skeletons often decorated books of hours (collections of prayers that were once popular amongst wealthy Europeans) to accompany a set of prayers for departed souls known as the Office of the Dead. Never too worried about being gentle or sensitive, the people of the Middle Ages sometimes decorated Office of the Dead pages with horrifying images of the undead – perhaps a warning of the fate that might befall a loved one for whom prayers were not said. Some of these illustrations make reference to specific legends, but the meanings and sources of others are lost to time. In this particular scene, two skeletal figures offer a young man a vision of his own future demise. Facing one’s mortality has been a frequent theme of artists across the ages.

Henry Fuseli, The Nightmare, 1781 (Detroit Institute of Arts)

If this iconic painting reminds you of a Gothic romance or horror novel, there’s a reason for that. The Swiss-born English artist Fuseli (1741-1825) lived and worked at the beginning of the Romantic era, a movement in art and literature that gave us novels such as Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and Bram Stoker’s Dracula among many others. Romantic painters sought a quality known as the sublime – darkness, decay, superstition, and accompanying emotions like thrill and horror. Sublime paintings took various forms, including stormy landscapes and dramatic death scenes, but The Nightmare was sensational in its time for the sexuality implicit in its hulking demons visiting a vulnerable, lightly-clad young woman asleep in her bed. Perhaps it can be seen as an early predecessor of today’s vampire and monster-centric romance stories in which fear, danger, and attraction can be similarly linked. Fuseli’s other works also involve the supernatural and the subconscious, and often feature fairies, monsters, and scenes from Shakespeare.

Francisco Goya, Witches’ Sabbath (The Great He-Goat), 1821-3. (Prado, Spain)

Famed Spanish artist Francisco Goya (1746-1828) lived during a particularly tortured period of Spanish history, and many of his works address violence and its underlying psychology with unflinching verity. Goya and his contemporaries had much greater things to fear than witches, yet he painted this theme several times toward the end of his life. The combination of debilitating illness and extreme disillusionment led him to create a series of bleak and disturbing “Black Paintings” on the walls of his home. This work may actually be one of the least horrifying. It calls to mind his two famous series of prints, The Disasters of War and Los Caprichos, both of which exposed and commented on the human shortcomings that cause war and suffering.

Edvard Munch, The Vampire, 1895 (Munch Museum, Oslo)

Norwegian artist Edvard Munch (1863-1944) was a Symbolist, an adherent of the late-nineteenth century artistic and literary movement concerned with expressing spiritual and intangible concepts through physical symbols. By all accounts, Munch was a tortured soul whose fixation with illness and death likely came from his father and sister’s early demises. His works, including his famous The Scream, clearly reflect his unrest through a combination of their subject matter and agitated, expressionistic aesthetic. Although it is now called The Vampire, Munch originally titled this work Love and Pain. It caused a massive scandal upon its first appearance and later had the dubious distinction of being labeled “degenerate” by the Nazis. Whether you choose the interpret the red-headed woman as a blood-thirsty monster or simply the passionate lover that Munch claimed she was, this image would not look out of place in a modern vampire story. While Munch’s work provides a distinct stylistic contrast to Fuseli’s paintings of a century earlier, the spiritual and philosophical ideas behind the two men’s art were not so different at all.

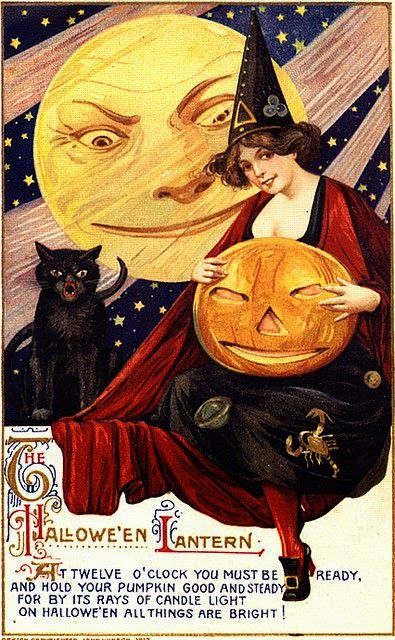

Today’s friendly festive form of Halloween took shape sometime in the early twentieth century. Accordingly, more pleasant images of witches, ghosts, and ghouls began appearing around that time, proliferated by modern printing and advertising. Cute and colorful illustrations of jack-o-lanterns, black cats, and children in costume decorated vintage greeting cards and magazines. These monsters might still have been shown with their iconic fangs, but they had no metaphorical teeth of any kind. The above witch, who appeared on an early-1900s card, is a far cry from the old crones painted by Goya. She is pretty, elegant, and completely without malice. Even the poem printed alongside her is cheerful. It has been argued that the many pretty witches in early-1900s publications were actually feminist statements of a sort – an effort by female consumers to assert their independence and perhaps reclaim a character that has been used to malign women throughout history. This character has transformed quite a bit since then just as the entire holiday has evolved in the past hundred years. It’s difficult to say what Halloween visuals will look like in another few decades, but they will certainly have taken on a new form once again.