Art Encounters | Magical Thinking

What’s the point in always looking back,

When all we see is more and more junk?– Manic Street Preachers.

A recurring problem when reviewing a work of art or an exhibition, is the perceived strengths and weakness of what we have encountered. To what extent are we engaged with the work outside the parameters of our own set of subjective concerns? The old adage of objectivity, of maintaining critical distance, is crucial; it’s held up as crucial in an age when the subject/object ‘thing’ has lost much credibility, and perhaps rightly so. Scientists ceased talking about space and time eons ago, preferring instead to bring once-oppositional terms into a kind of fractured totality: space-time. Philosophers have being doing the same, trying to gauge how we might think of objectivity like a space-time continuum.

So, instead the standard question of, “What are the strengths of the art, objectively?”- which can be translated as “How did you critically receive this exhibition outside of the parameters of your own individual self?”- I find myself asking more and more: ‘What have I brought to this experience of art in this moment that I wouldn’t have brought before?’

This is a question central to what the Art Encounters series is about. By refocusing analysis away from the object and back to the subject who encounters that object at a particular point in time, we are really asking what an object-subject ‘thing’ might look like when approaching criticism.

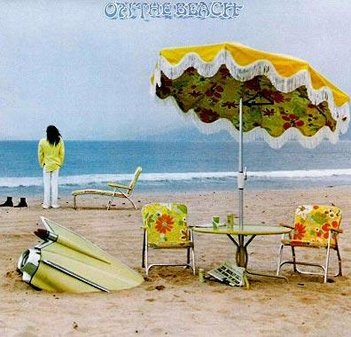

Take my last article as an example. I found myself listening to On the Beach over and over again and wondered why I had initially felt some ambivalence towards it. One particular line from the album stuck in my head: ‘I’m deep inside myself, but I’ll get out somehow.’ The line is from the album’s centerpiece ‘Motion Pictures,’ which I recall not liking when the CD came out, experiencing the song as a kind of self-indulgent dirge about the movies. Now, I felt as if the song was about me. This is not to say I was simply identifying with Neil Young. It is rather I felt swayed by the song to such degree that I began to invent a version of Neil Young for myself. I wanted to find about what was going on in Neil Young’s life when he was making the record because the ‘Neil Young’ I had invented was a mystery I wanted to solve. I now see the Art Encounters series as an attempt to solve certain riddles about why we experience things like we do and to then ‘get out somehow.’ When I was experiencing grief to a degree I had never experienced before, I found myself drawn towards things that could suck blocked emotion out. This draw, however, can feel like a double bind: to ‘get out somehow’ means going further into the self. I can only get further inside myself when affected by something on the outside. There was an upside, however. This process brings with it an epiphany of sorts. The effect is indiscriminate: it doesn’t care what form the art that we encounter takes. For someone who works in the arts, and comes up against the many arbitrary divisions that make up the world of art and culture today, this is very liberating.

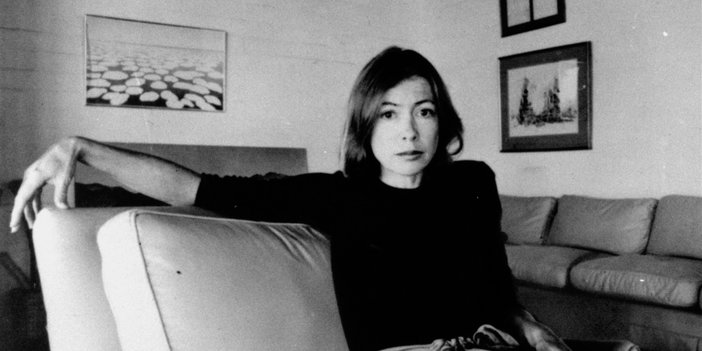

[pullquote]I now see memory as a retrieval process that has personal resonance is central to the Art Encounters series, as a project about the ‘me’ or about the fluctuating self.[/pullquote] I now understand something of what Joan Didion means when she describes the year after the death of her long-term partner as the ‘year of magical thinking.’ To think magically is to approach the world as indiscriminate. open to all sorts of possibilities. “I understood for the first time the meaning in the practice of suttee,” Didion writes with reference to the Hindu tradition, “widows did not throw themselves in the burning raft out of grief. The burning raft was instead an accurate representation of the place to which their grief (not their families, not the community, not custom, their grief) had taken them.” The ‘burning raft,’ metaphor is the ‘beach’ Didion or Neil Young felt initially stranded on, until able to turn a beach into a shore. Both were stuck on the beach.

Of note, however, is that Didion recalls encountering a poem she had previously studied in her college days as the effective trigger for bringing about the change from reason into magic. The poem Rose Alymer jumps out at her afresh; her grief is a catalyst for a kind of thinking that moves across memory, that brings a fresh perspective to bear on her own past experience. Change for Didion, Robert Pinsky says, comes from accepting absence brought about by death. “The absence,” Pinsky notes about Didion’s memoir, “is meaningless, but memory can retrieve meaning, or at least partial meaning.” When Didion recalls this poem, she realizes the power of memory in the mourning process.

I now see memory as a retrieval process that has personal resonance is central to the Art Encounters series, as a project about the ‘me’ or about the fluctuating self. I identify with Didion’s suggestion that she progressed over time from wanting to replace cherished memories of her loved one with less meaningful ones, and instead began reconstructing thoughts so as to preserve the meaning around those cherished memories. She declares, as the book concludes, that she had “been trying to substitute an alternate reel” but now she was trying “only to reconstruct the collision, the collapse of the dead star.” The change in Didion’s approach, from trying to alter memory so that it wouldn’t impact on her to such a degree, to trying to preserve via a process of cathartic reconstruction, is part of a broader distinction made by her between grief and mourning. Grief is a passive affair which involves struggling to accept loss, while mourning is an active affair that involves working through loss. For most, the ‘work’ will involve building some form of shrine, making mementos that enshrine our memory in photos, paintings or perhaps films (regarding this process I can’t but think of Christian Boltanski’s work). Others, like me, are drawn towards writing.

In a moment I would mark as serendipitious (as I was formulating these ideas), I was made aware by a virtual friend of an upcoming show by Irish artist Clea van der Grijn at Limerick City Gallery of Art interestingly titled: Reconstructing Memory. The show, the said friend informed me, deals with mourning traditions from a cross-cultural- in this case Mexican-Irish- perspective. The premise for the exhibition took shape from van der Grijn’s longstanding interest in mourning traditions, an interest she has been pursuing since her younger brother died ten years ago. I responded to the parallels with Clea’s concerns in the exhibition and what I’m doing in these articles with some degree of unease, leading to a self-questioning process: What, in fact, am I doing? Feeling a bit put out by a friend saying ‘what I do’ is similar to what someone else does, generated uncertainty regarding what I do (hence the current article). I perused the documentation of Clea’s exhibition online, and found myself drawn towards some of the recurring objects in it. The first of these objects is a simple bunch of flowers, in some instances alive, in other’s very withered and dead. It soon becomes apparent that the flowers are actually Marigolds, central to the Mexican tradition of mourning. As soon as I saw them, my curiosity was elicited and I began to wonder why these objects in particular elicited my curiosity? Is it because they are configured as symbols of forgiveness and love in art throughout the ages? Or is it because the symbolism of a bunch of flowers is central to research in Chantal’s Akerman’s D’Est: Bordering on Fiction (a haunting film about Eastern Europe that was made in 1992), and Abbas Kiarostami’s Close-Up, (a 1988 Iranian film about a man impersonating a famous film director) that I’m currently engaged in?

I’m not sure. But what I do know is that the withered flowers sparked a memory of the bunch of flowers that had been placed outside the front door of my father’s home after his death, which I watched slowly wither in time in the following weeks. The slow decay of the flowers couldn’t detract from the fact someone had placed them there, which really meant that their decay could never override the memory represented by them being there in the first place. I looked again at the online catalogue that accompanied Reconstructing Memory, zoning in on Marigolds, and was brought back to that time. Were the flowers Marigolds? Who knows? And does it matter?

The memory, however, drew me towards the images of large-scale oil-based paintings I gather to be a central feature of Reconstructing Memory. The series of paintings is titled: Marigold Fields, and each one appears to be an act of preservation celebrating the life contained in these soon to die flowers. I am drawn towards their surface, penetrated by dots bursting forth into life. The dots might well represent memory. Hence, in bursting forward, not quite taking the form of Marigolds, we can imagine them as Marigolds coming into being, just like a memory coming to consciousness. The paintings appear to capture the flowers in flux while, at the same time, illustrating what is reconstructed in painting them. The series therefore expresses an aim of the exhibition as I experience it as a whole: to explore memory when reconstructed in art.

The exhibition is made up of many such reconstructions. Found objects particular to Mexican life and culture compete with the actual Marigolds themselves in the many object forms they take, all of which is part of a multi-faceted exploration of days of remembrance in Mexico dedicated to celebrating the dead returning to the living. This is best understood as a form of collective ritual given over to turning what Didion calls a burning raft into what others call a sailing ship. The absence of meaning once associated with loss takes the form of memory reconstructed in time. Taken in this context, the Marigolds about to bloom in Marigold Fields can be interpreted as memories co-existing in time and space, brought to life through an act of painting.

In The Work of Mourning, a book that gathers together all the obituaries Jacques Derrida wrote about friends, the philosopher distinguishes the mourning process from simply thinking about death, the latter a principle concern of philosophers the world over. Within this text, Derrida writes about needing to recognise that the dead are ‘in us,’ noting of his friend Roland Barthes that ‘all we seem to have left is memory.’ Although he was unaware that he would devote much time to exploring what he meant by this, we should dwell on the phrase ‘in us,’ as opposed to ‘in me,’ in the context of the book’s title. The plural here is significant. It suggests that memory must be shared in some way in order to contribute to the mourning process. The reconstruction of memory is memory in the form of a sharing: as work or as a work. Derrida’s emphasis on memory ‘in us’ coming out in mourning brings some of the concerns in this series into some sort of synchronicity with those explored in the exhibition: Reconstructing Memory. Maybe the line from Young’s ‘Motion Pictures’ ‘I’m deep inside myself, but I’ll get out somehow’ makes reference to this process: a process of sharing that involves translating ‘me’ into an ‘us.’ And this ‘us’ Derrida writes about, materialises, crucially, as such, only when we pluralize ourselves in the work of art, and the memory shared takes the place of the void.

Reconstructing Memory by Clea van der Grijn is open at Limerick City Gallery of Art from now until June 18th, 2017

Feature Image: From Clea van der Grijn’s Reconstructing Memory