Letting Go | Stories from the Mexico-United States Border

Neil* is a US army veteran of Native American descent who worked in El Paso for 18 months. He came to Ireland in 2017.

“I lived two miles from the border, up in the Franklin Mountains in eastern El Paso. I used to sit on my balcony, smoking a cigarette, drinking a beer, and watch Federales and the cartel get in firefights every night. Then border patrol would be on the other side,” he chuckles, “and once they start getting shot at – it’s madness. I’m not joking.”

Neil is stout, built like a boxer, his frame clad with muscle and sinew, of the pragmatic kind rather than

aesthetic. His jaw clenches and unclenches unconsciously from years of chewing gum, his eyes dart elliptically about the room. Sometimes he will say something and look me in the eye, shrugging, apparently even more amazed by what he just said than I am. Neil moved to Ireland to be with his son; during our interview, he receives a call from the boy’s mother, Neil’s ex-wife, with whom he shares custody.

After completing military tours in Afghanistan and Saudi Arabia, Neil returned to the US to study law. In one of his classes, Neil was presenting an argument which impressed a visiting judge, who invited Neil to intern in his legal office in Texas, which specialised in narcos cases. Neil didn’t mind only receiving an intern’s salary, as he was already drawing a military pension.

“El Paso, Texas, the very centre of the narco universe. Texas is insanely massive. It takes fourteen hours to drive across it, going eighty miles an hour. So basically… think of El Paso like a Hawaiian island, surrounded by a sea of sand and brutal mountains. It’s beautiful, but there ain’t shit out there.”

Neil asks me if I know Los Zetas. “Basically, they were a group of guys from the Mexican military, decided they were tired of being paid shit – one of their elite units said ‘screw this. We are highly trained, we can basically take whatever we want out of this army base.’ And they started their own cartel – and they just spread. They were the people that went completely medieval.”

“You did run into a lot of those people, just going out at night. They weren’t hiding it. If you work for the cartel, unless they were working on a case against you in the states – pretty good chance your family is living in El Paso. They’re not selling the drugs in Juárez or Monterrey: everything’s getting sold in the states, they’re bringing the money back – they don’t want to shit in their backyard. The cartel’s a giant spider. It’s linked to anything with money in Mexico. Violence, human trafficking… Organised crime is intertwined with their government.”

Given Neil’s military training, it wasn’t difficult for him to spot someone carrying a gun on their person. Occasionally, he would walk into a bar and notice that just about everyone present was armed. West Texas was just as wild as the name suggested.

“My friends and I, we went to a range out in the desert. We were just shooting some old rifles and we got rolled up on by some Hell’s Angels. They tried to kick us off and we were just like, no. But it would have been way worse for them. We had trucks; they had bikes, man. They would’ve got shredded.” Neil then patiently explains to me that one can’t legally own a gun in Mexico without a permit, so most cartel guns in Mexico are smuggled over the border.

“The university there is big, the University of Texas in El Paso. They have these huge dome windows that face Juárez. It’s literally half a mile to the fence, and somebody shot out those windows while classes were in session. Can you imagine being an eighteen-year-old student, and somebody just starts letting go with an AK-47, in your classroom? But some asshole on the other side of the border probably thought that was hilarious.”

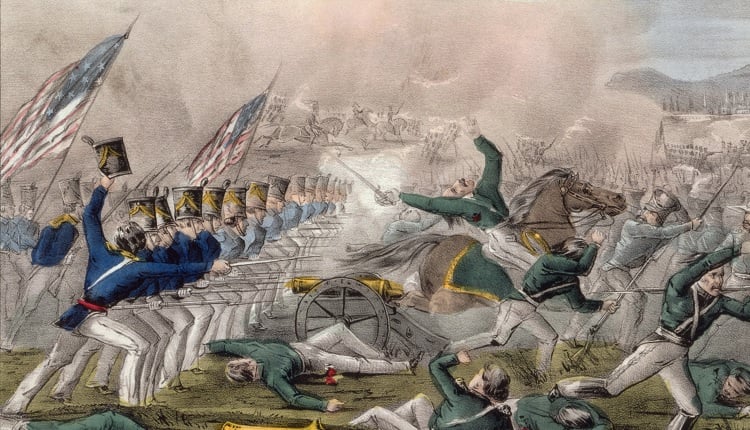

Neil happened to have a friend who lectured in the same university, for whom old grudges died hard. “She was still mad about the Mexican-American war. The bitterness runs deep. Sixty years ago, border patrol in the states was a joke. It was a guy on a horse: ‘have a good day, howdy!’ Now, there’s walls and fences and… look, the border cuts right through the city. El Paso and Ciudad Juárez, when they first got settled, it was one giant city. The border cuts right through it. It’s like three hundred metres – in some places it’s ten.

“Economically, it’s night and day. For standard of living, some parts of Mexico are very close to Afghanistan. From the I-10 going towards Los Angeles, you can look down into Juárez, and there’s a poorer section right next to the fence. You can see all these shanties. Some of the places don’t have roofs. It’s just cardboard. And the majority of people along the border have family on both sides.”

Would people commute back and forth across the border, for work, to visit their families?

Neil nods.

“People get killed doing that,” he shrugs. “You don’t get searched going into Mexico, but coming back – you’re going to be waiting at least an hour to two-hour line on a giant bridge. That’s where a lot of murders and stuff happen. When you’re unarmed, perfect time right?”

“So – El Paso’s like an island – this is super offensive,” he sniggers, “I’m going to go on a little rant. They’re very nice to you – until you don’t speak Spanish. (It’s garbage Spanish, it’s a different dialect from Catalanian or Mexico City.) And then if you’re tan and you got dark hair, they are insulted that you don’t speak Spanish, because they think you’re Mexican. My second week, some lady told me I should be ashamed of myself because I didn’t speak Spanish. I told her that I wasn’t even fucking Latino, that I was Native American. So – yeah, they’re kinda dickheads.

“They want the perks of being Mexican, but they don’t want to actually be Mexican. They want the culture, the food; they’re extremely liberal in that city, which is interesting because there’s a giant military base there. They don’t want to be viewed as American.”

I ask him – if they’re extremely liberal, why do they all own guns?

“You’ve gotta survive, man.”

I ask Neil, has he spent much time in Mexico himself?

“Mexico is gorgeous. I used to party in Ciudad Juárez in high school, when it was stable. If you went crazy, it was forty dollars in a weekend. I wouldn’t go to the border cities, they’re narco-controlled, they’re hellholes. There’s this really cool bar in Ciudad Juárez that Al Capone used to hang out at.

“So the last time I was there, I was chilling with a friend of mine in this bar, pictures of Al Capone and John Wayne on the walls. And these two rival factions just start lighting each other up with AK-47s, right outside. With a piece of glass between us. It’s just like that. They don’t give a shit who gets hurt, they just want to get paid.”

Neil offers me some thoughtful advice, should I ever decide to go to Mexico to find a wife.

“Callate! Remember that word, you’re gonna need it!”

Isadora* was born in Torreón in the north and moved to Guadalajara at ten, later attending college there. She moved to Ireland in 2014.

“The first time I went to the United States I was eight, I went to Disneyland. Going to a plane, listening to people who don’t speak my language – so weird for me, but so exciting – I want to know what they were saying. When I arrived to Disneyland I saw a completely new world. It was the first impression I had.”

Isadora is tall, slim, statuesque, her long Nordic frame and pale skin betraying her Scandinavian heritage. She smiles compulsively, relentlessly; in her line of work (my line of work too, not so long ago), smiling is as much a part of the uniform as the black frock and flats.

She spent her teens and college years in Guadalajara. “High school was pretty good, because we had this American kind of programmes. American football, I was a cheerleader.”

Guadalajara didn’t used to be a dangerous city to live in, but has become so since Isadora left. “Because the narcos, in the whole Mexico. The narcos and people – just keep living, you know? You cannot stop your life just because things are happening. People get used to this news every day. Just keep living.”

Isadora tells me animatedly that Guadalajara is the home of mariachi music – but “this is for you, like Irish music”: young people in Mexico listen to mariachi music about as frequently as Irish young people listen to trad. In Mexico, the young people only listen to American and English music.

“The heads of the narcos, you never see them on the street. But if you are in a café, you notice. You have the smell, this sense of noticing people who are in this business. They’re everywhere. The narco selling ecstasy in the nightclub, the narco driving a truck. They’re everywhere right now.”

Was anyone you know ever involved?

“I have a friend – I don’t know if it’s narcos or not, but it comes with everything – I have a friend who was visiting another town in Mexico and he was kidnapped. You know, express kidnap. They took him and made him give his credit cards and money, then left him outside of the city.” She’s never seen any crime in the US.

I ask Isadora: Guadalajara may be a wealthier city than, for example, Ciudad Juárez, but not exclusively. Is there a demarcation line visible, between the well-off and the less well-off?

“Yes, and it’s amazing because it’s just one street. From one side you can see the poor ones and the

other one you can see the huge houses and fancy cars. The money and the no money.”

Las Vegas, New York, Miami, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Chicago – she’s been all over in the US.What does she notice?

“The first thing is infrastructure. I’m from a big city in Mexico, and every time I go to United States I feel my city is

very small, even though six million people live in my city. Everything is so well planned in United States.”

Do people in America notice that you’re from Mexico?

“When I speak,” she says flatly. “I don’t look American or Irish, but I don’t look Mexican, so people are very open. But when I start speaking, they notice. You can’t get rid of the accent. They change – you can see in their eyes or their faces, ‘you are not what I was thinking you are’. People to me have never been rude or hostile or – it’s the way that I look, they don’t have this first impression that I’m not like them. But I have seen people who, just from the way that they look – they just treat them like nobody, like they don’t have any value. When I’m in America and when I’m in Mexico as well.”

For many in the American south, Guadalajara and the surrounding area is almost like a retirement village, serving much the same function as Florida, with its endless acres of gated retirement homes: they want a quiet life.

“Old people are very nice to us, to everybody. It’s the young people who don’t have the right concept. They feel that they can be rude to us, even in our own country.

“I’ll say one thing – Americans hate Mexicans and Mexicans – Mexicans don’t like Americans, but we just don’t know each other, really.”

None of Isadora’s friends who emigrated went to the US, instead favouring Spain or Canada. There is less competition for individual jobs in Canada, and a Canadian dollar stretches further than a peso. Canadians, her friends report, are by and large very welcoming to Mexicans, but her friends don’t appreciate the Canadian climate as much as the Spanish. There’s no way, however, that a Mexican can pass themselves off as a Spaniard: the differences between Iberian Spanish and Mexican Spanish are as pronounced as those between British and American English.

I ask, you’ve been speaking English since you were in college.

“I’ve been trying to speak English since college,” Isadora smirks.

I ask her, do you think in Spanish?

“When I was working in the restaurant as a waiter in Ireland, you speak English every day, every day, every day,” she says, snapping her fingers. “And right now in the office I’m working, there is a lot of Spanish speakers, so I speak in Spanish every day. So I feel like I’m going backwards. Even though I cannot speak proper Spanish anymore either! My brain is like, divided.”

The last time Isadora was back in Mexico was in February of last year.

“It does feel different going back there. I was there and I was thinking ‘What these people are doing is wrong! Why these people just throwing garbage on the street? Just put it in the bin!’ Just simple things. I don’t feel 100% part of my own country anymore. And I don’t feel 100% part in this country!” she laughs.

What does she miss about Mexico?

“Family, of course, but – I have to say, I miss food. Always fresh, always green, always full. Businesses: the restaurants, the clothing stores, the shopping malls, they close at twelve at midnight. You actually have life after work. This kind of metropolitan life. There’s always something to do in the city.”

Isadora’s paternal grandfather was born in Norway to a Norwegian father and Spanish mother, before moving to Spain and then Mexico, where her father was born. Her mother’s parents were both of Spanish descent.

“My mom is a saleswoman,” she laughs. “She says that she started working at eight, just selling anything door-by-door. She started selling this chocolate powder – she was like eight, so everybody was buying it. Right now, she’s selling funeral packages.”

I wonder to myself if there’s a greater demand for funeral packages in Guadalajara than in Dublin, but I don’t pursue the point.

Her mother wanted Isadora to go abroad, see the world, sow her oats, see what she wants for her life. “My dad is the one who is like, every time I speak with him he’s like ‘When you coming back? When you coming back?’” she laughs.

But she doesn’t think she’ll ever go back.

Letting go is hard enough once: you can’t pick it back up again once you’ve done it.