The Gifted Paradox | Understanding giftedness in children

“I’m really worried about your daughter,” the teacher told me. “She’s developmentally delayed. She’s definitely got a problem with maths, and she has no social skills. I’d be worried about her language, as well. She doesn’t say very much.”

I left the school with tears of fear and guilt obscuring my view. My child was seven, and I’d missed the fact that she had special needs. How had I missed something so obvious that a young teacher, only two years out of college, had spotted in a matter of months?

The waiting list to access an educational psychologist through the school (NEPS) was about two years long. A private assessment would have cost me €700 – which I didn’t have. I’d heard about the Centre for Talented Youth, Ireland (CTYI) assessments, though, and they were only €50. I could find €50. My logic was that the CTYI test would let me know how slow my child was, so I’d have an idea of what I was dealing with, what support groups I needed to approach, and what I needed to do to make my little girl’s experience of life better.

Imagine, then, my surprise, when I got a letter telling me that her special educational need was that she’s actually gifted, and inviting her to attend classes at the CTYI. I borrowed the money to get my girls privately assessed, and was told that my little one – at seven – had the problem solving and intellectual processing capabilities on a par with the average twenty-five year-old. Few things have scared me as much in my life. I had no idea what to do with this information – what support I could find for her (and for me), and how, exactly, I was going to ‘manage’ her situation.

The teacher had correctly identified that my child had no friends – but that wasn’t because she had ‘no social skills’; it was more to do with the fact that she couldn’t find anyone with whom she had enough in common to forge a friendship. This continued until last year, when she spent three weeks at CTYI, and met people who were like her; teenagers who – like mine – struggle with asynchronistic development.

Her “maths difficulties” were reflective of the fact that her teacher couldn’t understand her abilities, so labelled them ‘dis-abilities’. By the time she was nine, she had finished the Irish maths curriculum and – even more incredibly – managed to explain quadratic equations to me in a way that I understood them for the first time ever. As for her perceived “language difficulties”? She’s just a woman of few words, and she always was. In fact, while you might be impressed by her maths, language is where she really excels.

By now, you’ll think I’m boasting, but I’m really not. Having a child in Ireland who is anything other than ‘average’ is difficult – more (of course) for them than for those of us who love them. Let’s be honest here, though, most people think that being really smart means you’ve won some genetic competition. There’s a sense that you’ve got enough now, and you should just shut up and be grateful. Except, it’s not that straight-forward.

Children who are intellectually gifted need special educational consideration, support, and help in just the same way as children who have learning difficulties. They may not need the same interventions, but they do need the same level of investment in their education as every other child in the system. Sadly, they don’t get that here.

Teacher-training doesn’t address the issue, and – unlike most other countries in the Europe, the Americas, and Asia – Ireland has no provision for the special education needs of gifted children. Currently, the only classes that cater for these needs are found at CTYI. It’s expensive, and beyond the remit of most Irish families – especially if they have more than one child who qualifies to attend.

Given that about 5% of the population would qualify to attend, I hardly need to point out that it’s not only rich people who are smart – but that only rich people have the luxury of exploiting their smarts.

In 2004, the Irish Government did a number on the most intelligent kids in the country – they introduced The Education for Persons with Special Educational Needs Act, 2004. This dissolved the National Council for Special Education, and omitted the term ‘exceptionally able’ from legislation. It’s predecessor, The Education Act, 1998 referred to “educational needs of students who have a disability and the educational needs of exceptionally able students.”

According to the 2004 Act, however, special educational needs means the educational needs of students who have a disability. Conflating ‘special needs’ with ‘disability’ doesn’t do anyone any favours; least of all those children who are exceptionally able, and have some (or all) of the special needs associated with being gifted.

“Talent is a thing – but it’s not everything,” Claire Hennessy says. Claire – whose giftedness was recognised when she was a child – has been teaching at CTYI for 14 years, so she’s more than familiar with the special needs of these kids. She explains that, when she meets them for the first time, these children are not used to getting things wrong. They need to learn how to learn, and a huge part of that, is learning that they are not always right, and that’s okay – that it’s actually desirable. “Sophisticated learning means asking questions and saying ‘I don’t know’,” Claire continues. “But kids are often shamed for not knowing, so they don’t ask.”

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (of which Ireland is a signatory), states that “the education of the child shall be directed to: (a) The development of the child’s personality, talents and mental and physical abilities to their fullest potential.”

Now, there are those who claim that all children are gifted. Frankly, that’s rubbish. All children are gifts, all children have gifts, but not all children are gifted. The term Gifted is used, interchangeably, with ‘Gifted and Talented’ and ‘Exceptionally Able’.

Broadly speaking, however, there are three characteristics of ‘giftedness’; advanced intellectual ability, a high degree of creativity, and heightened sensibilities.

Gifted individuals are born with unique brain functioning – a true cognitive difference – which must be addressed in their education, if it is to be in any way effective. They are not simply smarter – they think differently, they learn differently, they perceive differently, and they sense differently. Simply put, a gifted child can absorb, synthesize and analyse information easily. They can use logic and critical thinking in very complex ways. They are curious, and tend to have a more keenly developed sense of justice, and better memories than others their age.

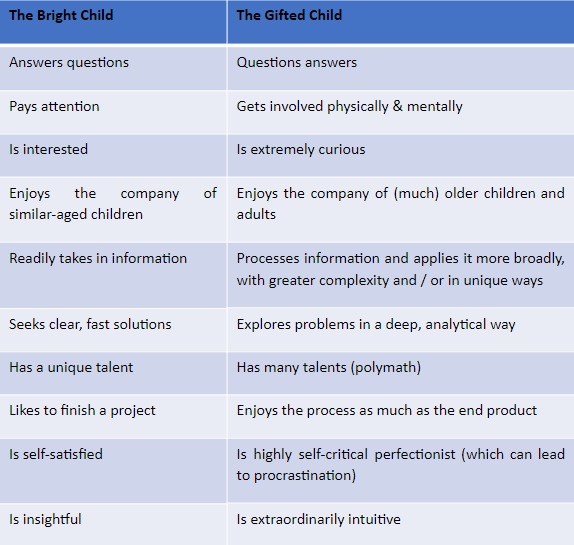

There are differences between highly intelligent (or ‘bright’) children and those who are termed gifted:

The special needs of gifted children are social and emotional as well as academic. Sure, they learn quickly and easily – and remember what they have learnt; but they’re highly self-critical, and hold themselves to a higher standard than most of the rest of us. They also have difficulty switching off. Their brains are constantly whirring – analysing situations, problem-solving and coming up with ideas. And, sometimes, coming up with new problems.

When children have disabilities, their access to special education services is determined on the basis of need; if the children need a service, they are generally regarded as having a right to one. With gifted children, however, access to special provisions is often based on a determination that they deserve these special services. There is a general resentment in providing educational resources to those already seen to be ‘basking in talent’. If education is a right, however, it cannot simultaneously be a privilege.

Gifted children who do not have their special educational needs met often fail; I am aware that that’s an emotive word, so I used it advisedly.

Under-stimulated gifted children quickly become frustrated and bored. Like children with other special needs, these children can struggle with a loss of self-esteem, self-confidence, and problems evaluating their self-worth. It may seem like a paradox, but when you are not afforded the potential to flex your intellectual muscles, you begin to doubt that they exist. This, in turn, leads to anxiety, stress, fear of going to school, and fear of failure.

School is not a site of joy and learning, it’s a site of being mis-understood and, in some cases, trauma. Often, if they’re not challenged, these children stop trying, if their efforts to extend themselves are slammed by a teacher and a curriculum that doesn’t cater for them, they start to lose interest in school – which leads to underachievement and exam failure.

On a psychological level, these children can manifest higher levels of stress, anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation than their non-gifted counterparts. All of these combine to reduce the quality of life of gifted children (and the gifted adults they become), and can negatively impact on their love of learning. Physically, they can suffer stress-related insomnia, headaches, and digestive ailments. Unable to maximise and exploit their potential to the fullest, they risk becoming a burden on the health services as they try to ameliorate the psychological damage, and its physical manifestation(s), associated with this lack of opportunity.

Being gifted, when that giftedness isn’t recognised, supported and exploited, isn’t really a gift at all.