Why are you sending me colours in my head? An interview with cyborg artist Neil Harbisson

What would you do if someone hacked into software connected to your brain? This may sound like the premise of a thousand and one questionable dystopian films but it happened to Neil Harbisson. Of all the people who might find themselves on the receiving end of a neuro-hacker, artist and cyborg activist Neil is perhaps the most likely. He was born with achromatopsia, a rare form of colour-blindness that left him only able to see in greyscale. In 2003 he attended a cybernetics lecture by Adam Montandon and together they invented the eyeborg, an antenna-shaped device that transposes colour into sound. Each note represents a gradient of the colour spectrum and allows Neil to experience the world in colour.

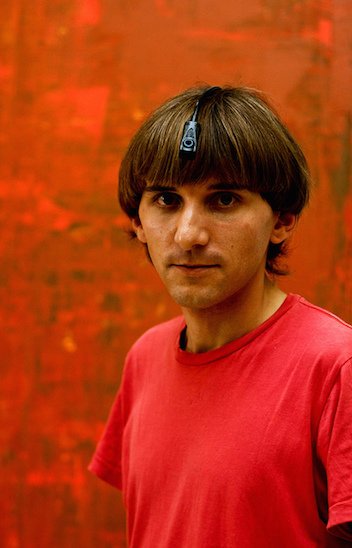

Shortly after this initial success, Neil decided to implant the eyeborg permanently into his skull. After being turned down by an ethics panel he eventually convinced a doctor to perform the surgery anonymously. Since then the eyeborg has become a permanent part of his body. As we talk on skype I can see it scrunched down under his baseball cap. But the eyeborg is more than the optical equivalent of a prosthesis. ‘I am a biological cyborg,’ he tells me. ‘What really changed the way I identified myself was the union between the mind and the software. The fact of being a psychological cyborg was what really affected me the most.’

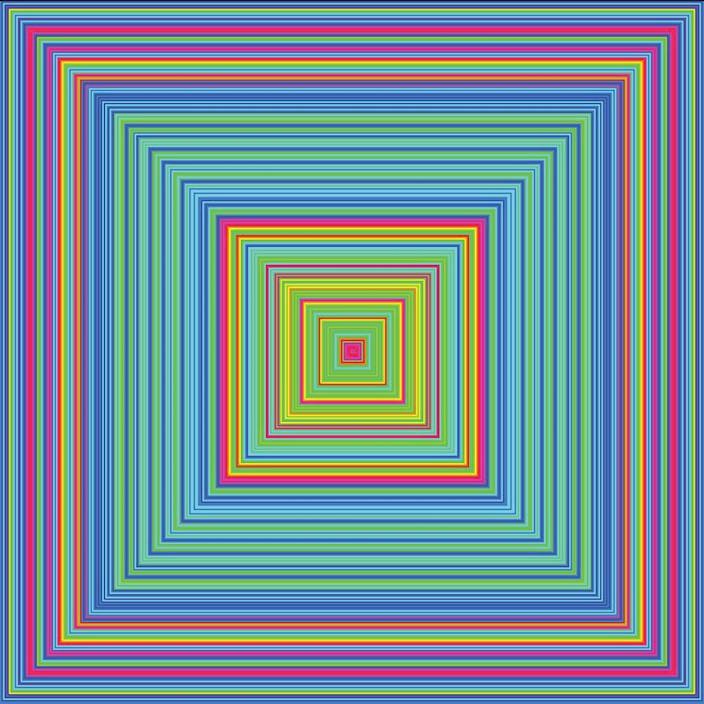

Hearing colour has become a gateway to new approaches to art. Neil has made portraits of speeches by Hitler and Martin Luther King. He listens to people’s faces and has translated images of people like Woody Allen and Philip Glass into sound files. Neil has also been active promoting cyborgism and cyborg rights through his work with the Cyborg Foundation. People have been eager to take part in the Foundation’s work, Neil tells me. The choreographer Moon Ribas, Cyborg Foundation co-founder, has had a sensor implanted under her skin that detects earthquakes. Another participant has installed a camera in his finger. Neil has been working to find a way to use his own body to charge the eyeborg. Blood circulation, he says, is one possibility.

But reactions to the eyeborg haven’t always been so enthusiastic. ‘For a while I had it hidden,’ he tells me. ‘But it doesn’t work when I go out in the street. People think I’m hiding something or spying.’ He had a run in with police outside of a protest who mistook it for a camera and has been thrown out of movie theatres by people who thought he was filming. Sometimes people don’t know what to make of him. More often than not the eyeborg acts as a Rorschach test for the latest technology. ‘In 2012 people thought it had something to do with Google Glass’ he says. ‘Now people think it’s a selfie-stick.’

The divided response to Neil’s work is a reminder that cyborgs aren’t always treated kindly by pop culture, running the gamut from Terminator to Rachael in Blade Runner. In film there’s usually something of the uncanny valley about cyborgs. Technology is often presented as the antithesis of our humanity which has become a concern as more and more of our lives play out online. Holiday resorts offer tech detoxes. Commercials for tablets and smart phones play down their own mechanical reality. There are trees, there are flowers. There are some very happy families. No one is busy becoming a cybernetic organism.

Fears about the integration of technology into our lives have also been ramped up by revelations about government surveillance and the auctioning off of our personal information. When I ask Neil about privacy concerns he immediately assumes I mean other people’s fear of the eyeborg. He is, understandably, mildly exasperated by the question. ‘‘Everything I see or record goes to my brain’ he tells me. He looks surprised when I say that I mean him. ‘There’s no output’ he says, which prevents any violation of his privacy. And then he pauses,

‘It happened once. Someone hacked into my head.’

The hacker sent him sounds that triggered different colours before, suddenly, stopping. ‘I had a breach of privacy from that person’ says Neil. ‘I didn’t dislike it… I actually liked the fact that someone was able to hack into my head and take over. But I don’t know who this person was. I wish I do. I wouldn’t be angry or upset with him.’ I ask Neil if it felt like just another form of social interaction. ‘Yeah,’ he says. ‘It’s like you’re walking in the street and someone stops you and talks with you.’

Not many people would greet such an intimate interaction with a stranger with so much equanimity. But Neil is nothing if not open-minded. He is busily rethinking the relationship between ourselves and the objects we make. Rather than following the traditional division of technology and humanity he argues that technology has the potential to make us more human. By creating new senses, technology enhances our experience of the world and each other. These senses, he points out, ‘might seem strange but they’re very normal in other species.’ Neil’s optimism is a striking departure from traditional suspicions about technology as a foil for our humanity. ‘It’s a way of connecting with reality in a much more natural way and that’s something that’s been very hard for people to see’ he tells me. Initiatives like his might be one way of escaping deeply entrenched ideas about where our humanity ends. The eyeborg it seems, is the way forward.