Do Creativity And Psychosis Share Genetic Roots?

Art is brain made. Art can be an escape valve, a revival but sometimes endowed with a strange or psychedelic character. Are artists alienated and crazy? Whereas scientists confirmed the link between creativity and mental illnesses, a new epidemiological study found their common denominator: the genetic variation. The genetic risk predisposing to schizophrenia and/or bipolar disorders might encode for creativity.

The “alienated genius” notion

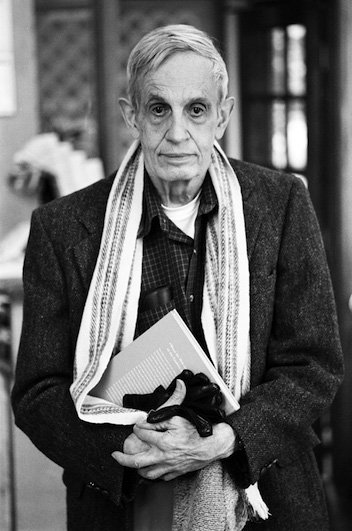

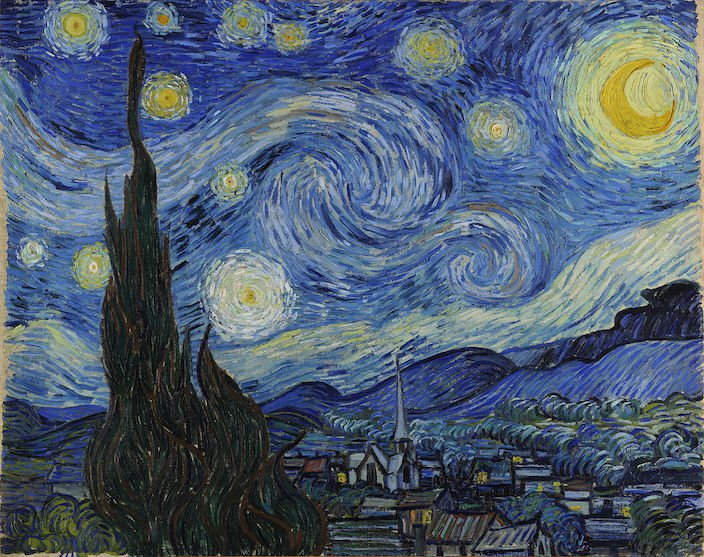

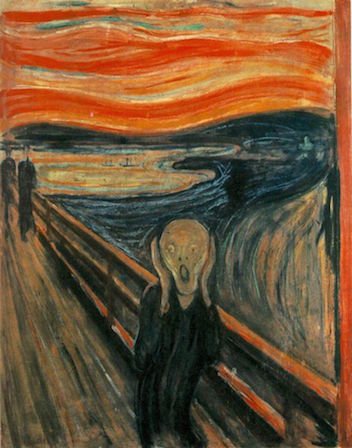

Part of the human being is to appreciate and to create art. We can be completely overwhelmed by a painting, a book or a symphony because they can evoke a diverse palette of emotional responses ranging from happiness to intense fear. Art requires creativity but does it also require a hint of craziness? Could creativity be a byproduct of madness? There are many examples of marginal person with exceptional artistic abilities accompanied by severe mental illnesses. Among them, to cite a few are, Vincent van Gogh (the “disturbed” Dutch painter), John Nash (a Nobel Prize winner mathematician who suffered from paranoid delusion) and Virginia Woolf (an author affected by mood disorders). Numerous studied have confirmed the connection between “madness” and “genius”. Data showed that people in creative professions such as artists and scientists, are more often treated for mental disorders (e.g. bipolar disorder, schizophrenia; 1, 2). The overrepresentation of psychiatric pathologies in creative occupations is even stronger in the category of writers who show high rates of schizophrenia, mood disorders, substance abuse and suicide (3, 4).

Surprisingly also, the relatives of geniuses are more prone to develop psycho-pathologies as compared to control subjects (3). For example, Einstein had a son who was schizophrenic and the case repeated with the novelist James Joyce whose daughter (pictured above) was also diagnosed with schizophrenia. Thus creativity and crazy minds seemed to be a family affair. Recent studies strengthen this idea showing that the first-degree relatives (parent, sibling and child) of patient affected by schizophrenia and bipolar disorders are significantly overrepresented in creative occupations.

A behavioural package shaped by our genes

Given previous observation that madness and genius character run together in families, could these characteristics be predicted by the genes? Yes, according to a new study, published in Nature Neuroscience (5). As certain genetic variations can be associated with schizophrenia and bipolar disorders, a predictor for genetic risk scores for these psychiatric disorders can be calculated. Particularly, these genetic variations taken individually have a minor impact, but their accumulation can play a determining role and so increase the genetic risk for these pathologies. From the whole genome of 2,636 Icelanders, researchers found that people with a high genetic risk for both schizophrenia and bipolar disorder tended to be employed as an artist or belonged to artist societies (actors, dancers, musicians, visual artists or writers’ union; 5). Thus, creativity and psychosis might share genetic roots. This finding supports the idea that genetic factors have a direct influence on more than one trait of the human personality.

Why would nature genetically regroup such unrelated phenotypes? As mental disorders are known to impair social life and fertility (6), one could think that natural selection would tend to delete such genetic variations that predispose them. But this is not the case. One possibility for this existent paradox may be explained because mental illnesses come in pairs with creativity. Thus, by considering creativity as a positive factor in terms of reproductive success, the disadvantage of mental disorder could persist via the compensation of a beneficial one, here the creativity. However, one has to note that having a creative profession or occupation is not a measure, per se, of what is creativity. And defining or measuring creativity is still a matter of debate for scientists.

Nevertheless, this study shows that the link between psychopathology and personality traits might not only exist at the behavioural level, but also at the genetic level. Fundamental questions still remain. For example, does the genetic risk associated to other psychiatric disorders also have an impact on creativity or other “positive” personality traits? To this aim, further studies revealing genome variations as landmarks of psychiatric disorder would allow answering this question.

While a connection may exist between creativity and madness, it is not causality. In other words being “crazy” does not make you creative, or does it?