Cancer series part III: Resistance

Cancer is clever. People speak about this extraordinarily diverse and complex group of diseases as if they were one disease and ask us impatiently when we are going to “cure” it.

The reality is that many researchers, myself included, don’t believe we ever will “cure” cancer. For a start, trying to develop a single “cure for cancer” is like trying to develop a single cure for AIDS, depression, the flu, a broken leg, and supporting Fulham football club (even after relegation). We’re making progress in designing treatments for specific cancers, but cancers adapt quickly, with many of them evolving in such a way that they can stop themselves being killed by drugs. This is called resistance, and presents an enormous challenge. Some of the best treatments we have will only work for a limited time, before resistance kicks in. But understanding resistance will help us defeat it, and when we defeat resistance, no one will have to fear cancer anymore.

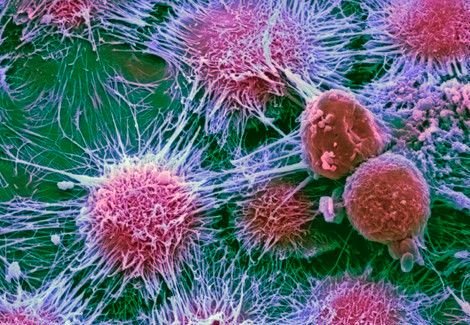

One of the ways we study resistance is using cell lines. These are cancer cells which were taken from patients and then kept alive in the lab. These cells, which are fed with a sugar solution and grown in plastic flasks, are a long way from a human with the disease. But they let us quickly and easily get to know how a cancer works, and how its behaviour can be changed by a gene or protein change, or a drug. Some cell lines are grown in the constant presence of a particular drug. Most of the cells grown this way will die, but a few survive, and in time, these resistant cells will take over. It’s like bands of resistance fighters regrouping after their army has been destroyed. Cell lines that have been conditioned to become resistant over time in this way are very valuable as they mimic what happens in patients who stop responding to therapy. They help us find out how cancer cells changed when they became resistant, and to test whether new drugs will work in resistant as well as sensitive patients. But the most valuable research we can do is when patients opt to donate their tumour to research after their surgeries, and we can look at how cancers from “responders” are different from cancers that were taken from people for whom the drugs stopped working.

Some cancers become resistant by switching on special survival proteins when they sense danger. One such survival protein is PI3K, which is activated when cancer cells are attacked by a drug. PI3K, once activated, goes on to activate other proteins which have different effects that help cells survive under stressful conditions. One will trigger cells to reproduce more, another will hack into the body’s healthy blood supply to hijack nutrients away from healthy cells, and another still will block the signals that tell a cell to commit suicide when it gets old to make way for other cells. Drugs are being designed to block this kind of chain reaction, or pathway, and last year, a clinical trial showed that a drug called Afinitor could potentially thwart resistance caused by the PI3K pathway in some cancers by blocking the action of one of the chemicals in this pathway.

Another way cancers avoid being killed by drugs is by using special pump proteins which physically ejects the drug from the cell. One such protein is called P-gp, and we evolved it as a way of protecting ourselves against infection. Its normal function is to push pathogens like bacteria out of our cells before they have a chance to make us ill.

Scientists have been trying to block the action of the P-gp pump for decades, but it’s turned out to be difficult to interfere with without harming the patient. However, every study that hasn’t quite worked has still been able to bring us one step closer. Just this year, an article was published in the journal BMC Cancer that reported a new drug may be able to reverse chemotherapy resistance caused by P-gp. More tests will be needed before we know if this drug can be given to patients, but the article is encouraging.

I said at the start of this article that I don’t believe cancer would be cured. I believe some cancers will always find a way to develop resistance. But I also believe that there will come a time when we know these resistance mechanisms so well that there will always be a new therapy, and cancer will become a long-term illness, treated with one drug until that drug stops working, at which point the patient will be switched to a different drug. We’ve made dazzling progress in the last few decades with the invention of cancer-selective side-effects that don’t have the side effects of chemotherapy, and this improved quality of life for patients will only get better with time. The future is full of challenges, but also, full of hope.

If you haven’t done so go back and read part I & part II of this three part series on cancer