No Hysteria | The Dismissal of Female Pain

It was August 2002, and 17 year old Leona was curled on a trolley in A&E, rocking back and forth with pain, no energy left to cry anymore. She had been admitted the night before with debilitating pain in her lower abdomen. This was nothing new to her at this stage, although it was particularly intense this time, and had lasted over a week. She had been treated for bowel spasms following another visit to A&E in January of that year, but no further investigation had been made into her symptoms. That August, she underwent surgery to remove an enormous cyst that had wrapped itself around her fallopian tube. She lost the tube and the ovary.

A 2001 study from the University of Maryland titled The Girl Who Cried Pain showed that although female patients report pain more frequently and severely than male ones, women’s pain is treated less aggressively than men’s, and female patients are likely to be given a psychiatric diagnosis where male patients with the same symptoms are not. A later study from Yale in 2015 discussed delays in the treatment of heart attacks in female patients. It illustrates that women experience heart attacks differently to men, but that heart attack symptoms have traditionally only been described in relation to those experienced by men. We also see a common scepticism surrounding medical conditions that are traditionally considered “female”, such as fibromyalgia, as well as ones that are specific to those assigned female at birth, such as endometriosis. A popular article in The Atlantic in 2015 addressed this. What causes this tendency in the medical profession not to take female pain seriously, often with severe consequences?

Leona was 12 when her periods started. She suffered from strong cramps from a young age, but it wasn’t until just after her 16th birthday that the intense pain that prevented her from walking began. At first it came just for a day or so in the middle of each month, but before long she began missing school and was unable to move at all for days at a time. Her GP prescribed the contraceptive pill to try to regulate her periods and manage the pain. Her first trip to hospital in January 2002 was a traumatic experience.

“After spending the night on a plastic chair crying in A&E I got put on a trolley in the morning to wait for a doctor to get around to us”, she says. “It was completely overcrowded and an awful experience.”

[perfectpullquote align=”right” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”#8D3AF9 ” class=”” size=””]“It seemed like he was trying to get people out of the hospital and free up trolleys rather than actually investigating.”[/perfectpullquote]

The doctor she saw sixteen hours after arriving at the hospital didn’t thoroughly examine her. He asked a few questions about the pain before quickly moving on to query her appetite and concluded that she was suffering from bowel spasms, prescribed medication for that, and sent her home. “It seemed like he was trying to get people out of the hospital and free up trolleys rather than actually investigating what the pain might be”, says Leona.

When the pain continued to recur every month, worse each time, her mother begged her to return to hospital. Reluctant to spend another night in agony on a plastic chair only to be sent home, Leona refused, but agreed to see her GP. She was referred for an ultrasound scan, scheduled for October of that year. In the meantime, however, the pain became unmanageable. She missed one of her Leaving Cert exams because of it. Finally, in August, when the pain was still debilitating a week after its onset and showed no signs of subsiding, Leona relented and returned to A&E. This time, she was admitted within a few hours.

She doesn’t remember much of the next two days, which to her are a blur of agony. Eventually, however, she was told that she had an ovarian cyst and would need surgery. The medical team promised her and her parents that they would do their best to save the ovary, but when they operated they found that the cyst, which was the size of a grapefruit, had grown a tail and strangled it. The ovary, the cyst, the tube, and substantial other dead tissue was removed. Internal bleeding was also found. When Leona left the hospital the following week, she weighed just four and a half stone.

In the years immediately following, she and her parents were furious that a proper investigation wasn’t conducted upon her first visit to hospital that January, that could have prevented her condition from becoming so serious. When her parents received a hospital bill for €600, they informed the hospital that they were taking legal advice and would not be paying the bill. The hospital never chased them for the money.

Now 32, Leona has been on hormonal contraceptives since she was 16 to help prevent any more cysts from developing on her remaining ovary. This has caused her problems with her mood and weight. She fears for her chances of having children, and later abdomen pain has often sent her into a panic.

Christine was 31 when she had her fourth child. It was a difficult labour, during which she pulled a muscle in her chest and tore her vagina badly, requiring eight stitches. Her afterbirth pains were particularly bad this time. The hospital doctors gave her over-the-counter painkillers and sent her home twelve hours after the birth, advising her to see her GP if she needed anything stronger. She found that the chest injury caused her particular problems, so she quickly decided to do just that.

“Just one whole day after giving birth”, she says, “I dragged my broken body to the GP for some proper pain relief.”

Her GP refused, telling her that labour and the subsequent pains are a natural occurrence that the female body can tolerate. At this point the pain was so severe that Christine was in tears, but her doctor told her that that was “just baby blues, not real pain”.

She was inconsolable. Desperate to help, her husband went to the same GP and told her that he had hurt his back. He came home with a prescription for stronger painkillers.

These stories provide anecdotal evidence for the basis of the 2001 study. In particular, the ease with which Christine’s husband obtained a prescription compared with the brick wall she met shows a doctor prejudiced against treating female pain as aggressively as men’s, and her GP’s dismissal of her pain as “baby blues” backs up the hypothesis that women are often given a psychiatric diagnosis for pain.

But the problem is not confined to pain related to the reproductive systems of those assigned female at birth. It extends to many different types of pain women experience. Anne is a 56 year old woman with a number of diagnoses of pain conditions. She suffers from degenerative disc disease (a condition that occurs when one or more of the discs of the spine deteriorates or breaks down), sarcoidosis (an auto-immune disorder that occurs when cells in the body clump together to form small lumps called granulomas, which can develop in any part of the body, causing pain, inflammation and fatigue), and fibromyalgia (characterised by chronic fatigue and pain in the muscles and fibrous tissues).

Anne’s pain began in her early 30s, mostly back pain at that time. She spoke with her GP at an early stage and was advised to exercise and lose some weight – good advice, but difficult to follow for someone in pain. For a while, she put the pain down to having had three children and the strain of daily life. It worsened progressively, however, and she sought medical advice a number of times over the years, with little success.

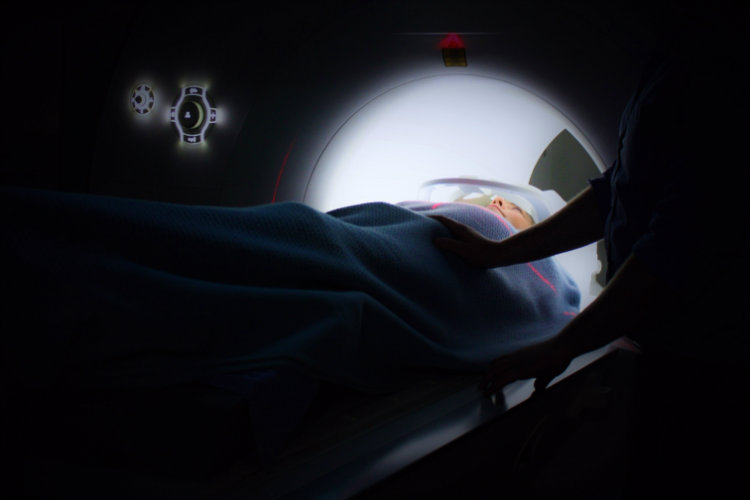

When her back went into spasm for the first time in her mid 40s, she began to seek investigation and treatment more aggressively. Eventually, she was diagnosed with degenerative disc disease, and underwent numerous different treatments for this over the following years, with varying degrees of success but no lasting relief. An MRI scan in 2009 was never followed up on, and no further investigations were made for other underlying conditions.

[perfectpullquote align=”right” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”#8D3AF9″ class=”” size=””]She went about life permanently exhausted, and her quality of life seriously deteriorated. [/perfectpullquote]

Over the years, Anne’s pain spread from her back into her hips, legs, shoulders, arms and neck, and it was keeping her awake most nights. She went about life permanently exhausted, and her quality of life seriously deteriorated. While consultants and her GP advised her to take ibuprofen and exercise – things that weren’t working for her – she fought steadily for further investigation. Finally in 2015, after a scare that looked like cancer and some very invasive surgery, she received the diagnosis of sarcoidosis, followed shortly by that of fibromyalgia.

By the time her sarcoidosis was diagnosed, it had become chronic and so advanced that it was affecting her bones. Sarcoidosis of the bones is rare and difficult to treat. There is no cure, only pain management strategies and efforts to halt the progress of the illness, which can be difficult for the body to tolerate. Had Anne’s condition been diagnosed sooner, it may never have affected her bones.

Anne’s life is impacted on a daily basis, as it can be difficult to make plans to do even something as simple as meeting a friend for coffee, not knowing whether just sitting there will cause her severe pain. She works two days a week, but even this is problematic due to pain and chronic fatigue. Pain often prevents her from sleeping, leading to further fatigue. Sensitivity to touch means that even a hug can cause pain. She wears loose clothes and comfortable shoes most of the time because they don’t hurt.

She finds it difficult explaining her limitations to others who don’t understand her conditions, and has encountered scepticism from people who didn’t think she “looked” sick. With regard to fibromyalgia in particular, she has been asked “Is that a real thing? I read somewhere that it’s all in the head.” – a common misconception often encountered also by endometriosis sufferers. This scepticism is regularly found around conditions traditionally considered female, partly because early medical research was generally carried out on male bodies.

For her part, Leona knows that her experience was not unique, and she expresses frustration about the difficulty she and other women have encountered having their pain taken seriously. “I had to be in absolute agony before they listened to me”, she says. Similarly, it was only when it looked possible that Anne had cancer that an in-depth investigation was carried out and her sarcoidosis was diagnosed. In both cases, these women knew that there must be a reason for the pain they were experiencing, but no one took them seriously. That had severe physical implications for them both, and in Anne’s case even impacted her mental health as she questioned herself: was this pain real? Could it really be in her imagination? The lasting impact was such that, even after her diagnosis, she still felt the need to explain and justify herself.

The Girl Who Cried Pain offers a number of explanations for the gender disparity in the treatment of pain conditions. These include prejudice against women complaining of reproductive-related pain because it’s considered “natural”, the mistaken belief that men are more stoic so that when they do complain of pain “it’s real”, and the the sexist trope that women are simply more likely to grumble. It appears likely that gender bias and sexist cultural messaging leads doctors to make assumptions about female patients that can detrimentally affect the standard of their care. The study also cites other research which shows that three times more people believe that women have a naturally higher pain tolerance than men, than the other way around, when there is no evidence to suggest that this is true.

So what’s the solution? The study concludes by recommending more attention to this phenomenon in the medical school curriculum and awareness-raising among healthcare providers of the disparity. It is worth noting that Leona’s, Anne’s and Christine’s experiences all occurred after the publication of the study, showing little notice taken of its findings. A shift in the focus of research to a more gender-balanced approach is slowly taking place, but it will take time before this changes attitudes in the medical community. The removal of sexist misconceptions about women from general society will also need to take place before prejudices can truly be challenged.

For her 25 years of undiagnosed pain, Anne deserves the final word. “You learn to pace yourself with a chronic pain condition,” she says. “You learn to understand that you can’t be Wonder Woman; even being Ordinary Everyday Woman becomes a humongous chore.”