The Mendicity Institution | Homelessness, Community, & Journalistic Humility

It’s my second time visiting The Mendicity Institution, and as I walk up to the front door a man is loudly talking to one of the staff members, Simone Sav, in a language I don’t recognise. When Simone sees me, the conversation finishes up and I walk inside.

Hearing a variety of different languages appears to be normal in the Institution, where a number of services are offered to the homeless community. Exact numbers are not available, but the majority of patrons come from Eastern European countries. In order to provide counselling, and accommodation and employment advice, the staff rely on their knowledge of Romanian, Polish, and Russian.

The Mendo, as its patrons refer to it, has been in service since 1818. “Mendicity” refers to begging, which the centre was orginally set up to suppress. The service today operates on a similar model to the one set up in 1818: to provide basic nutrition and small-scale employment in order to reduce the numbers of homeless individuals relying on begging to survive.

A new meal every day

On the first day I visit, two cooks in the kitchen are busy making pots of a meaty stew that will be served with potatoes. When people go up to the counter for their plate, they’re also given a banana that serves as dessert for the day.

When I take a walk around the dining area with Charles Richards, the manager, people seem to be enjoying the food. As they sit at wooden tables, we walk up and interrupt them. I smile, and shake people’s hands while Charles explains to the people eating their food that I am a journalist – a word many of them don’t seem to understand. One man asks me what a journalist is, and I tell him that it means I’m writing an article. I’m not sure if this helps.

The Mendo has recently started to focus on teaching targeted working English to homeless people who don’t speak the language, which comprises of specific vocabulary that can be used in an industry setting.[pullquote]The Mendo has recently started to focus on teaching targeted working English to homeless people who don’t speak the language, which comprises of specific vocabulary that can be used in an industry setting.[/pullquote]

This means that sentences like “Hi, I’m a journalist and I’m writing a feature piece on the homeless community” are met with nods that I can’t be sure convey understanding, and I swallow the default journalistic catchphrases that would follow this, such as “Can I get a quote?” “How do I spell your name, for when it goes to print?” “Is it okay if I record this?”

Instead, I fall back on interviewing the staff, because I’m confident that they understand me. I learn that the food centre runs on a strictly ‘no questions asked’ basis, and food is served to anyone who comes during the kitchen’s opening hours. Monday to Friday, breakfast is served for a half hour at 9am.

On Saturdays, breakfast runs for an hour from 10am to 11am. Lunch is served Monday to Friday from 10.30am to 1pm, earlier than most of us would be used to, but is intended to provide a sense of structure. On average, between 15 and 20 people attend the breakfast service, while the lunch service serves approximately 70 people a day.

Violeta Mooney, who works in the Mendo office on a part-time basis helping the homeless find employment, tells me that the kitchen is challenged to create new meals everyday, and offers a “huge variety” of dishes every week, due to an abundance of ingredients provided under the Bia Food Initiative.

The Mendicity Institution began working with the Bia Food Initiative about six months before my visit. With a slogan of “an appetite for sharing,” the aim of the initiative is to match surplus stock in supermarkets with organisations that can put it to good use. This means that on any given day staff from The Mendicity Institution will collect stock from Lidl or Tesco on Thomas Street that is about to go out of date, and decide what meal to cook up.

At breakfast few days previously, there were yogurts and little bars to take away. When it came to lunch, spicy chicken wings were the meal of the day, with teacakes for dessert. According to Violeta, little surprises like dessert stop people from getting bored with the food and encourage them to ration out their meals.

The quality of the food appears to have fostered the appetite for sharing that the Bia Food Initiative aims for, as many patrons pack away some of their food in a takeaway container. “They sometimes eat half the portion and bring the rest to someone else on the street,” Violeta tells me.

I look at the food invoices, I visit the kitchen, and I see people enthusiastically eating meals, but I don’t talk to anyone eating the food “on the record” to learn how dessert affects their life. This is partly because I’ve been told that some of the men can be spooked by cameras, while others may have outstanding warrants.

I can’t justify explaining reporting guidelines about always being able to name a source in article to people who often are missing formal documentation such as passports because they are living on the streets.

When people don’t have somewhere to sleep at night, is it ethical to report about their food? Should a journalist only use quotes when they have a full name and way to contact the person in question? Or does this mean that some voices sometimes won’t be heard?

Building relationships

Food is used as a way to foster a spirit of community in the Mendo. Charles tells me that the food centre is a way to “befriend” the people who need help in a low-pressure environment, as they tend to reject forming relationships initially. Once someone is a regular, and sees that the services are beneficial and non-threatening, the Mendo will try to offer counselling, referrals to addiction programmes if needed, and employment and accommodation advice.

When I later sit down to write the story, I’m advised to try and form relationships with some of the patrons of the shelter so I can add in voices from the homeless, rather than speaking for the homeless, and I wonder what I can offer to this community.

Charles tells me that many of the people they see come from Latvia, Lithuania, Poland and Russia because being homeless in Dublin can be considered better than being “destitute in their own countries.” As communities are built between them, people who attend the centre will often learn a communal language such as Polish or Russian to facilitate easier conversation.

The centre will work to repatriate those who would want to return to their home counties, or who would be entitled to welfare from their home countries. Despite having a good working relationship with various embassies such as the Romanian embassy, repatriation is often difficult. Some are from Eastern European countries that don’t exist anymore, some have lost their passports and birth certificates, and some haven’t had any connection with their families since they left. Without formal citizenships to any country, and without homes, their community becomes the people they surround themselves with. Charles paraphrases a quote from a patron, which sums up the situation: “homelessness is their nationality.”

Working for Dublin

The Mendicity Institution believes that the homeless community can be used as a resource for the Dublin 8 community. The Institution employs a number of men who are considered as long-term homeless, meaning they have been living on the streets for longer than a year. They must be committed to sobriety, and the job works like any other: Charles tells me that if they don’t turn up, “they get their P45;” if you don’t work, you’re fired. The shifts are split up over the week, with employees receiving two-hour shifts that take place in workshops twice a week.[pullquote]The aim of the Bia Food Initiative is to match surplus stock in supermarkets with organisations that can put it to good use.[/pullquote]

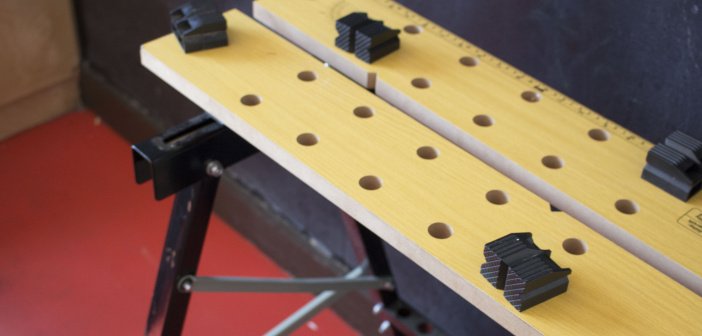

Simone Sav, an Institution employee who is in charge of the workshops, explains the concept. “It’s low skill, low risk,” with initial projects starting as simple as creating coasters made out of dyed rope, or painting walls. “You focus on making something, and you get better at. It’s not stressful, but it’s work. You have to present work (…) it gives routine.”

As people at the workshops become gradually more confident, Simone hopes they can progress to more skilled work, which the Institution would provide training courses for, such as working with power tools.

As confidence and skills are gained, they can move onto other projects involving the wider community, taking the sense of camaraderie they built in the food centre and applying it to the wider Dublin area. Recently, a number of men who attend the service were employed to clean up the green area outside a local school, which earned them a Good Citizenship Award.

This goes back to one of the core principles that the Institution was founded on: that homeless people can be used as a resource, which in Dublin means that they can be used to fill low-skill job vacancies. However, it runs the peril of being a silent resource.

The Mendicity Institution is doing great work, and I know that I, for one, never considered the logistics of what it entailed to be homeless beyond shelters and sleeping bags. Yet it rankles my journalistic sensibilities to write this story, because I can’t tell the human aspects of what happens in this community, merely the logistics.

What do we do when the ethics of storytelling compromise the tale – do we throw them aside, telling ourselves it’s a means to an end to try and do some good, or do we leave those stories dead?