Can the Coalition Win Over a Young, Savvy Electorate?

Less than two months into power and Ireland’s new government is already in turbulence, as its coalition leaders jostle for position within the political Frankenstein they have created. Their failure to foresee and prevent the virus outbreaks in meat processing plants is the latest example of teething problems in Ireland’s bold political experiment. Michael Martin, Leo Varadkar and Eamon Ryan have been at pains to portray their unlikely alliance as a sacrifice for the greater good, but a deepening economic crisis and public health botches will only further erode the confidence of an already sceptical Irish public.

The shock of the pandemic has made it easy to forget how seismic February’s general election result was. An unprecedented surge in support for the left ultimately forced the country’s centrist/centre-right parties to coalesce into a single neo-liberal mass, forcing a petulant political elite to abandon a civil war dichotomy that the electorate had long ago lost interest in. Today’s voter couldn’t care less whose grandfather fought with whom during the revolutionary era, but feel energised by live social concerns like housing and healthcare. They expect more from their politicians than their parents did, and it is within this context that Fianna Fail, Fine Gael and the Greens’ pandemic performance will be judged.

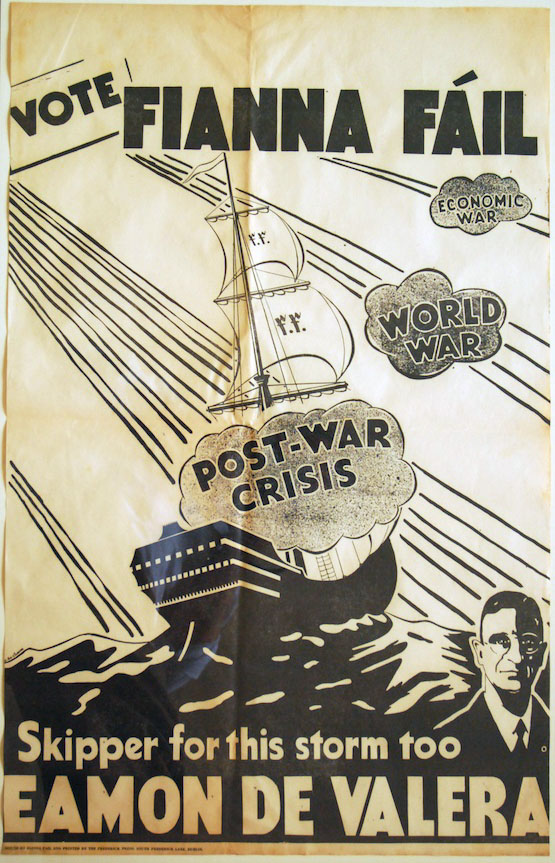

This is a level of scrutiny that Fianna Fail in particular is not accustomed to, and it already appears visibly rattled. The party spent most of the 20th century in government, propped up by the familial ties and the systems of localised patronage it established within the nascent Irish state. While the rest of the continent that century largely split along left versus right lines, the Irish lacked either the will or the leadership to debate the division of wealth and power in these terms. Instead the nation remained preoccupied with the outcome of the Civil War, as communities and individuals wrestled for a foothold in the vacuum left behind by the British administration. It was against this backdrop that Fianna Fail – and to a lesser extent, Fine Gael – thrived.

With party loyalty hinging on tribal allegiances more so than government performance, cronyism and corruption were inevitable consequences. It’s worth noting that in the years immediately following Britain’s departure from Dublin Castle, the country’s new political class was remarkably well behaved. TDs that slept overnight in their offices to avoid gunfire outside were required to reimburse the state for the cost of their meals, such was the enthusiasm for civic rectitude at the time. By 1935 however, under the original Fianna Fail government, the nation held its first public tribunal after Sean Lemass granted a lucrative mining license in Wicklow to two party colleagues.

The party’s love affair with venality reached its delirious nadir under Taoiseach Charles Haughey, whose contempt for fiscal probity ranged from the absurd (ownership of a private island) to the grotesque (stealing from Brian Lenihan Sr’s medical fund), all the while imploring ordinary citizens to tighten their belts. Haughey sat atop a rancid pyramid of brown envelopes that oversaw corruption on a national scale. The culture this created was more polluted than Barry Cowen’s breathalyser results. It permeated almost every aspect of civic society, the consequences of which can still be felt today with scandals rocking the police force, the banking system, sporting bodies, and so on.

Both Michael Martin and Eamon Ryan served as cabinet ministers under Haughey’s protégé Bertie Aherne, and it is this association that Martin is trying so earnestly to expunge. Recent opinion polls suggest he needn’t bother. For most voters his party is a dead brand associated with a hopelessly backward political system they’d rather forget. Worse, his waning popularity within the party might suggest that his attempts to cleanse its image might actually be alienating what’s left of his base.

While the challenges of the pandemic are unprecedented, the faces of Martin, Varadkar and Ryan are all too familiar to Irish society. Their coalition already lacked a firm mandate in February, while fiascos like the renewed lockdown in the midlands will only weaken their popularity with an increasingly impatient population. As our economic problems become more pronounced, the emergent class and generational divide now evident in Ireland will surely deepen. It is on this fertile ground that parties like Sinn Fein, Labour and the Social Democrats will continue to grow.

Why is @EamonRyan the actual epitome of when you have a problem and someone tells you to sleep it off?? pic.twitter.com/G3vmE0gDUh

— Alba Mullen (@alba_mullenn) July 17, 2020

The tough choices faced by the government would challenge any administration. But even greater than the health and fiscal challenges is the existential crisis Varadkar and Martin know they must now contend with. The longer they work together, the more it will become obvious that their party’s differences were based in feudal allegiances more so than policy. Their difficulty therefore is to convince a young, politically savvy electorate that their newfound alliance is anything other than a final, desperate attempt to avoid the break-up of a political monopoly. A century since the civil war, they will continue to tell us that their union is a selfless act to ensure stability, like dysfunctional parents getting back together for the good of children. Unfortunately for them, Ireland is growing up and wants nothing to do with their toxic relationship.

If you are white, male or even worse middle-class, Sinn Féin doesn’t want you. So much for an ‘Ireland of equals’ https://t.co/y4FBVsqppq

— Leo Varadkar (@LeoVaradkar) August 12, 2020