Help or Harm | Dublin’s Medically Supervised Injecting Facilities

Few social phenomena maintain a pedigree as long and unbroken as opiate use. With earliest evidence dating as far back as 3300 BC, humanity’s relationship with the opium poppy has been as enduring as another habit of ours – the written language. Unlike the effervescence of culture and art that proceeded the advent of literacy however, what has followed the discovery of this particular intoxicant is something much more fraught and ambiguous.

For millennia, societies have walked a fine line attempting to balance the wonderous ability of opiates to suppress pain with their ability to sink deep into our synapses and compel further use. Some have taken a punitive approach favouring harsh sentencing to suppress both supply and demand. Meanwhile others have adopted a health-led approach, still prosecuting suppliers, whilst leaving consumers in the hands of the healthcare system. The decisions a country takes in dealing with substance use have profound implications, not just for the users themselves but for how that society envisions the roles of policing and healthcare.

With an estimated 18,988 opiate users currently residing in the state, this not an exercise in political philosophy; it is real, it is now, and it requires immediate action. In responding to this crisis, successive governments have deployed a wide array of policies, however plans to roll out one specific intervention, medically supervised injecting facilities, have stalled amid controversy and objections from members of the surrounding community.

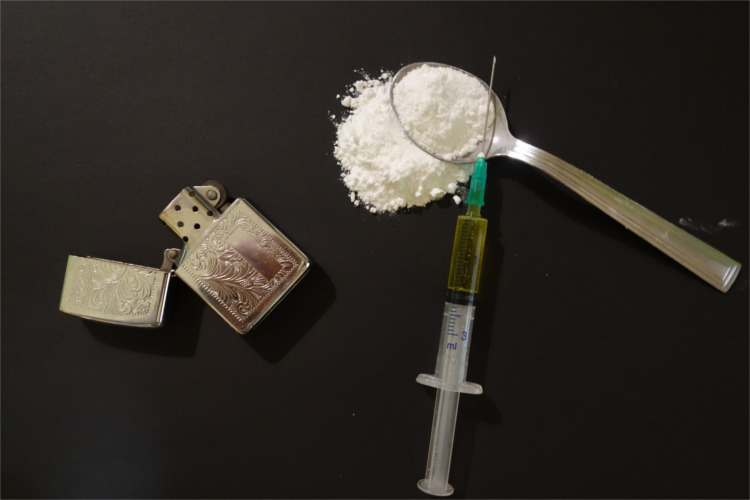

Medically supervised injecting facilities are services that provide a hygienic space for people to inject pre-obtained drugs under the supervision of staff trained in overdose response and other risk mitigation strategies. In essence, like many other harm reduction interventions, this policy accepts the limited ability of government to prevent individuals consuming drugs and instead focuses on making it as safe as possible for both users consuming the drug and the surrounding community. The logic behind this approach is that by targeting individuals who may not be ready to enter rehabilitation programmes, active users who are not yet known by drug services can be brought into contact with care providers. Here they may be counselled on how best to avoid disease and encouraged to seek further treatment.

One such centre was scheduled to open as part of a pilot programme with planning permission being approved in December 2019. The proposed site was the basement of the already existing addiction services clinic, Merchants Quay Ireland, located on the banks of the River Liffey in Dublin 2. However, in February 2020 a judicial review was submitted due to concerns raised by the local national school St. Audoen’s located 150 meters away from the site of the proposed facility.

Programmes operating out of Merchants Quay Ireland such as the needle exchange and night café have already drawn criticisms from members of the local community citing instances of antisocial behaviour. Quoted in an article published by the Irish Times last year, school management of St. Audoen’s described “public order problems; drug dealing; discarded syringes, bloodied wipes”. In a follow up article, those objecting to the proposed initiative pointed to what they believed to be an over-concentration of social services in the region, creating a pull effect bringing more drug users into the area subsequently resulting in more antisocial behaviour. As a result of this judicial review, the planned facility has been put on hold and its future stands in question.

Controversies such as these demonstrate the often-fraught nature of implementing social services. While most agree on the need to treat those suffering from addiction, how and where this takes place is routinely contested. Many initially in favour of needle exchanges, or other such services often become less sanguine when it is in their neighbourhood or adjacent to their place of business. Supporting something is easy when it is an abstract concept.

Is it fair though to accuse St. Audeons and the surrounding community of propagating a NIMBY approach to social services? It is hard not to feel some sympathy for the predicament that local parents and teachers find themselves facing. Even the most dedicated proponent of harm reduction might have pause for thought at the prospect of their child seeing someone intoxicated or coming across a discarded needle. After all, children too are a vulnerable group. Social welfare however is not a zero-sum game and it is indeed possible to question the wisdom of establishing a clinic like this in such close proximity to a primary school, whilst also remaining deeply committed to alleviating the plight of those in the grip of addiction. The question then remains – what is to be done with this proposed facility and how are the competing needs of two vulnerable groups to be balanced?

Ironically, the same concerns expressed by those against the introduction of this facility may in fact be exacerbated by its delay. Evidence from similar sites operating in Vancouver and Sydney indicate a reduction in instances of public injecting, discarded needles and other anti-social behaviours. The whole point of these facilities after all is to alleviate social problems in deprived areas – not make them worse. With a disproportionately high level of intravenous drug users, inner city Dublin is an apt example of where a facility such as this would have maximum effect. True, a medically supervised injecting facility could be installed in some distant industrial estate with minimal controversy but then what would be the point? If addiction services are not central and easily accessible, they will not be utilised.

Concerns raised by those in the community nevertheless remain valid and a consensus must be achieved if a facility such as this is to be successfully deployed. Staggered hours, a rigorous policing plan, and management of foot traffic are all interventions to reduce the negative side effects associated with this facility whilst still allowing it to carry out its much needed functions. Drug dependency will continue to destroy lives unless we take a proactive approach to engaging it where it resides, which is in the community.

Featured Image Source: Michael Lanigan