The Art of Persuasion | Inside Repeal’s Artistic Influence

Beneath a few layers of blue paint on the wall of Dublin’s Project Arts Centre is a 14 foot red heart. The words “repeal the 8th” are strewn across it in white, and were visible to all who walked by the building until the day they were covered up. Chip away at the paint and the vibrant red heart is likely to still be there.

The mural was painted by Maser, a street artist originally from Dublin who has been painting abstract graffiti around the city since the 1990s. The idea for a repeal the 8th mural came about when Andrea Horan, co-founder of The Hunreal Issues, asked Maser to create a design the group could use to promote the campaign. They had initially planned to share the design across their social media accounts, but Maser did one better and asked if there was a wall he could paint it on.

“It just sort of happened,” says Andrea. “Approaching different people always leads us to different audiences, and Maser was a good opportunity to get into a men’s space.”

The Hunreal Issues is a project aimed towards young people in Ireland who may not be actively engaging with politics, or feel comfortable discussing them. It is a feminist based media hub, set up by Horan and social media influencer James Kavanagh who, in the lead up to Ireland’s last general election, noticed that so many young people weren’t aware of the problems currently faced by those living in Ireland.

Armies of girls

Andrea says that her own passion for the repeal the 8th campaign made her want to push the women’s rights conversation beyond the boundaries of the often inaccessible political discussions so common in Irish media.

“There are an army of girls not voting,” she says, “or voting the same way their parents do. It’s no wonder politicians aren’t making women’s issues red line issues when it seems like nobody’s talking about them.”

Everybody was talking about Maser’s mural when it went up – and even more so when it came down. The giant heart stayed on the wall of the Project Arts Centre for just over two weeks before Dublin City Council requested that it be painted over, warning that the centre was in violation of a planning act. The council had received about 50 complaints about the mural, and over 200 letters of support.

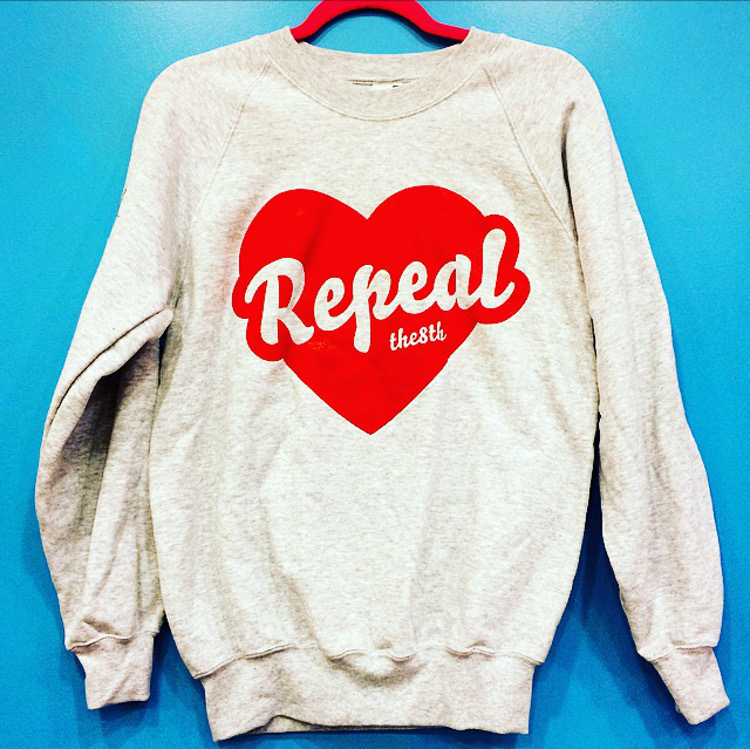

Maser’s design is now a popular example of activist art, instantly recognisable around the country by its bold colours and striking font. T-shirts, sweaters, and badges bear the design, making it a distinct symbol of the repeal campaign. Copycat murals have been drawn in markers and pens in bathroom stalls across Dublin, their outlines still faintly present even after others have tried to wipe them away.

Activist art, or protest art, is most commonly associated with graffiti, exhibitions, and street installations. It promotes creativity as a political tool with the power to challenge hegemonic cultural values and inflict real social change. Activist art differs from other art forms because it has a specific relation to the public sphere. It exists primarily outside of museums and galleries, using the public space to create awareness.

Writer and playwright Naomi Elster has used art in the past for this very purpose. In 2015 she wrote ‘I can do horror’, a poem about Ireland’s abortion law and the hurt that it has caused women.

Naomi says that learning about the 8th amendment horrified her, and that at first she found it difficult to write anything that accurately expressed the fury she felt.

“Words rarely let me down on the page,” she says. “I was so angry, so frightened, so utterly revolted and ashamed to be part of a country that would treat women, even girls, with such little compassion that when I tried to write about it in any form, I couldn’t actually express it (…) The poem came from that frustration.”

‘I can do horror’ was originally published on HeadStuff, and republished in 2016 in ‘Rise and Repeal’, a 1916-themed souvenir newspaper printed specially for that year’s March for Choice. Naomi says that writing the poem finally allowed her to transform her fears into courage.

“When Savita died, I was afraid to think about it,” she says. “I was afraid of how powerless I’d feel if I thought that the modern country in which I lived would stand back and let me die in fear in hospital rather than give me an abortion.”

Naomi believes that art has had a massive influence on the repeal movement, and that pieces so strongly grounded in the political have the power to change the way abortion in Ireland is talked about.

“People are more free to express themselves through art,” she says, “but the main impact on the campaign has been visibility, and the feeling of solidarity that comes from that.”

Blurring the lines

In 2016 a print of then Taoiseach Enda Kenny wearing a repeal jumper appeared on a wall on Dublin’s Camden street. The piece had drawn from images of activists modelling the jumpers that were launched by Ana Cosgrave’s Repeal project earlier that year.

Kenny’s unwillingness to address Ireland’s restrictive abortion laws has been a point of frustration for campaign groups since the repeal movement first started gaining momentum.

2017’s Strike 4 Repeal gave rise to the slogan “Enda, Enda, we want referenda.” Painted on banners and etched across signs, the chant contributed to the hundreds of other pieces of activist art that commanded the city that day, drawing the political into the streets and blurring the lines between the two.

These frustrations towards Irish politicians are also being expressed vehemently across social media, but not strictly through tweets and Facebook posts. Twitter user Ciaraioch, or Ciara, an artist and activist from Kerry, has been drawing cartoons reflecting women’s issues in Ireland for years. When she started to learn about the repeal movement, she turned her artistic intention towards abortion rights.

“All I’m hoping to do is start conversations,” she says, “and ideally help spread information and facts about the repeal movement while correcting any misconceptions that people might have.”

Ciara first started creating political art when she attended University College Cork, drawing topical cartoons for the college newspaper and student magazine. Her work only began reflecting feminist issues when she finished studying and got involved with her local abortion rights group in Kerry.

Activist art was largely influenced by the feminist movements of the 1960s and ‘70s, and aimed to give women a space in a culture that activists believed was ruled by the patriarchy. The art (which often included re-representations of the female body, social commentary, and challenges to traditional means of creating fine art) was not just made by women but also offered a female perspective, giving a voice to those who may not have had one before.

A lot of Ciara’s drawings focus on the experiences of women living in Ireland, emphasising issues like reproductive rights, sexual violence, and everyday sexism. Her latest piece features Wonder Woman clad in a repeal jumper.

Ciara posts her work on Twitter, where her drawings are often retweeted and shared hundreds of times among followers.

“The cartoons and graphics aim to be informative rather that persuasive or emotional,” she says. “(They) usually get either a neutral or fairly positive response, but there is always a small degree of negativity, usually from people who don’t agree with the campaign.”

https://twitter.com/Zeouterlimits/status/875648941466898435

The repeal movement has often been criticised in the past for being too “trendy.” In 2016 Irish Sun columnist Oliver Callan wrote that those supporting wider abortion access in Ireland were only doing so because it was “the cool thing to do.” He also said that wearing a jumper with the word repeal on it was a “too-cool trend rather than a courageous stand,” and likened the garment to something one might donn for an IRA funeral.

Similar sentiments were shared by journalist Larissa Nolan in The Irish Times on the day of Strike 4 Repeal, who said that being pro life made her “terribly unfashionable, and not in a cool, ironic way.”

Ciara believes that this perception of the campaign is a testament to how much support the movement has gained over the past few years – particularly among young women in Ireland.

It’s not a fad,” she says. “The “trendy” label is often used dismissively by people who either disagree with us, or haven’t engaged enough to understand the movement and the people behind it.”

Similar criticisms are held against celebrities who choose to endorse the campaign. In 2015, Liam Neeson narrated a short Amnesty International video called ‘Chains,’ which asked Ireland to lay “this ghost of paper and ink to rest.”

The video was branded as anti-Catholic by pro life groups with many members calling for a boycott of Neeson’s films. Irish filmmaker Phelim McAleer said that such celebrity endorsement pointed to a “disdain for the very real concerns of those opposed to abortion.” The Life Institute called the video a “crude propaganda piece.”

You’d be scarlet not to be knowin’

The Hunreal Issues’ Andrea says that there is nothing wrong with promoting a campaign a certain way if it helps more people get involved. She says that the repeal movement’s growth isn’t just visible in the clothes people wear, but in the steady reduction of abortion stigma, and the results of the Citizens’ Assembly.

“You need to make people comfortable engaging with it,” she says. “Our goal is to make things like this accessible. You have to make people want to get involved.”

As well as having a prominent social media presence where the project discuss the problems in Ireland “you’d be scarlet not to be knowin’,” The Hunreal Issues also run an online store selling all kinds of repeal related merch from T-shirts to leggings.

“There’s nothing wrong with the fashion route as long as the underlying belief is there,” says Horan. “People aren’t just wearing repeal jumpers for no reason.”

The jumpers don’t just say repeal anymore. They say whatever designers and artists across Ireland want them to. They’re criticising the criminalisation of abortion through art. They’re giving the middle finger to giant figure 8s across chests. They’re featuring Maser’s mural that still exists on the Project Arts Centre wall beneath a layer or two of blue paint – a mural that Horan says might being making another appearance on Dublin’s streets soon.

“We can’t rule out that it will go back up,” she says. “The mural became quite poignant because of the uproar. In an ideal world, when a referendum is called, we’ll get it back on a wall again.”