Ireland’s Carbon Hoofprint

Living in Ireland today, you’d have to be a hermit not to have heard of the Happy Pear twins. This energetic duo have dominated the culinary scene in Ireland over the last few years, gaining attention for their delicious vegetarian food and healthy lifestyle message. Love or loathe them, you can’t deny that their influence has been far-reaching. In a once obstinately omnivorous nation, more and more Irish people are now turning to vegetarian or vegan diets, or at least experimenting with meat-free recipes on a regular basis. And this is good news for the agriculture industry’s carbon footprint, or ‘carbon hoofprint’.

We are steadily becoming aware of the plethora of benefits a vegetarian diet has for us – for our waistlines, our cardiovascular health and our wallets. But cutting down on our meat intake also has a benefit on a global scale – for our environment.

Climate change has reached a critical level, with the concentration of CO2 in our atmosphere the highest it has been in 3 million years. 2016 was the third year in a row with record-setting surface temperatures. We are seeing more and more extreme weather events, climate refugees and destruction of natural habitats like the coral reefs.

If asked about the main sources of emissions and environmental damage, we tend immediately to identify the fossil fuel and transport industries as the main culprits. An important source often over-looked, however, and of particular relevance to us here in Ireland, is the agriculture industry.

How does the agriculture industry affect the environment?

Yes, you have heard correctly – farting cows (actually, their burps are the bigger issue). But there is more to it than that.

The term greenhouse gases (GHG) refers not only to carbon but also to methane and nitrous oxide. From an emissions point of view, it is through these non-carbon GHG that agriculture makes its main contribution. In terms of overall environmental impact however, we must also consider the industry’s heavy use of land, water and food.

Fertiliser production and use

According to a 2006 UN report, fossil fuel use in manufacturing fertiliser may emit up to 41 million tons of CO2 per year [1]. The real damage from these nitrogen-based fertilisers, however, is their release of nitrogen into the soil, simultaneously contributing to the emission of nitrous oxide and damaging soil quality.

Livestock digestion and waste

Ruminants with a multi-chambered stomach system (cattle, sheep, goats, buffalo) digest their feed in a process known as enteric fermentation, which produces methane as a by-product. These gassy grazers produce up to 86 million tons of methane per year [1], the most significant source of anthropogenic methane production. An additional 18 million tons of methane per year is released from stored animal manure, along with 2 millions tons of nitrous oxide [1].

Manure is stored to be used as fertiliser for farming and can also be sold commercially. Aside from releasing GHGs, run-off from incorrect storage of manure and spreading of slurry can lead to water pollution in the form of a process called eutrophication – “the increase in chemical nutrients in an ecosystem which results in excessive plant growth and decay”. This decreases O2 levels in the water, which in turn harms marine life. 15% of Ireland’s lakes and 19% of our coastal areas are affected by eutrophication. Run-off also contaminates drinking water supplies.

Land use

The livestock industry uses about 30% of the world’s surface land area. Land is cleared to use for pasture land and for arable land to grow crops used as livestock feed, with devastating effects on natural carbon sinks such as the Amazon rainforest. Livestock-induced emissions from deforestation amount to approx 2.4 billion tonnes of CO2 per year [1]. Deforestation also causes considerable damage to land quality and biodiversity.

Food use

There is a gaping deficit when we compare the amount of food it takes to feed these animals versus the amount of food these animals provide – it takes 5-20kg of feed to produce 1kg of beef.

This is admittedly less relevant in Ireland, where our cattle are primarily grass-fed. However, this redeeming factor to Irish agriculture can be problematic in itself. As people become more health-conscious worldwide, we are seeing an increase in demand for grass-fed produce, with a current annual growth rate of 25-30% in the US. Not only could this lead to Irish farmers bumping up production with potential disastrous effects on our water supplies/quality, it also increases the air miles incurred by Irish produce, thus increasing our emissions.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]It’s not just beef farming that puts a strain on water supplies. On average it takes 1,000 litres of water to produce just 1 litre of milk. [/perfectpullquote]

Water use

Producing 1 kg of animal protein requires about 100 times more water than producing 1 kg of grain protein.

On average, it takes:

- 15,500 litres of water to produce 1kg of beef

- 1,000 litres of water to produce 1 litre of milk

- 5,000 litres of water to produce 1 kg of cheese

- 3,900 litres of water to produce 1 kg of eggs

- 214 litres of water to produce 1 kg of tomatoes

Processing and transportation

Several tens of million tons of CO2 are produced by the transportation of feed, processing meat and animal produce and the transportation of produce [1].

Is this corn for factory farmed cattle? Grass fed cattle in Ireland will receive feed in the winter but it tends to be bails of hay gathered in the summer that grows fairly easily. It’s only if it is a particularly harsh winter when feed runs out that grain is bought in by cattle farmers. In the west of Ireland it is collected from fields that aren’t great for growing crops because the soil is very poor so its cattle or nothing.

How does Ireland do?

Worldwide, the livestock sector accounts for 14.5% of GHG emissions. In Ireland, agriculture accounted for 32.6% of total national emissions in 2013, according to the Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine, Ireland, compared with an EU average of 9%. Under the EU Commission’s Climate and Energy Package, enacted in 2009, Ireland is required to cut emissions by 20% from 2005-2020. The EPA announced just last week that we are on course for a reduction of only 4-6%, exceeding our carbon budget by 12-14 million tons of carbon. Emissions from agriculture look set to increase by 12%, according to a 2013 report from the Environmental Protection Agency.

This projected increase, is undoubtedly owed in large part to the government’s Food Harvest 2020 strategy, which would see a 50% increase in milk production and a 20-25% increase in value to the beef sector – an extra 300,000 cows.

How can farming improve?

I’m not advocating a mass cull of all cattle. Aside from being rather inhumane, that would incur serious economic consequences: agri-food and drink comprise around 5% of our national exports, and there are a lot of homes around Ireland whose livelihood depend on this industry.

However, if you’ll allow me the pun, ploughing ahead with business as usual is not an option. Increasing the national herd in the face of what we know about climate change and the ecological impacts of beef farming seems absurd. Instead, Ireland should use this knowledge to implement new sustainable practices and become a leader in climate-smart agriculture. In a step in the right direction, January 2012 saw the launch of the Agricultural Greenhouse Gas Research Initiative Ireland (AGRI-I) to research strategies in reducing agricultural emissions, with projects looking at sustainable soil management, ruminant GHG mitigation data and fertiliser use.

How effective is becoming a vegetarian/vegan?

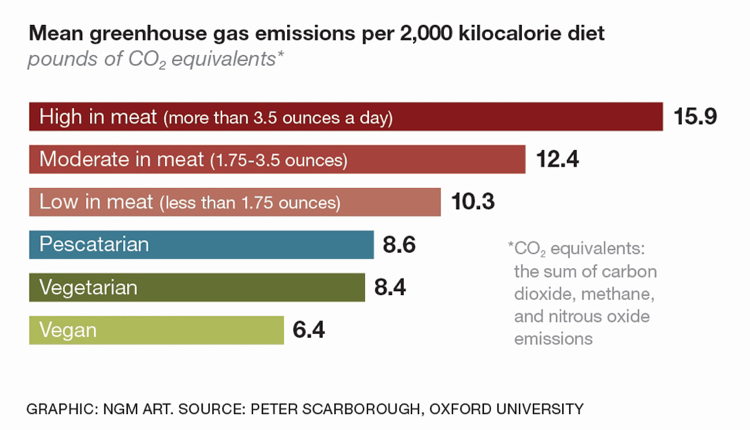

The idea of a dietary carbon footprint (or carbon ‘foodprint’) was first brought to my attention by an article in the National Geographic three years ago. It featured this succinct image, based on data from a study by Scarborough et al:

The study [14] shows that moving from a high meat diet to a vegan diet reduces an individual’s yearly carbon footprint by 1560kg CO2 emissions – for context, a return transatlantic flight from London-New York adds 960kg CO2 emissions to your tally.

The only thing more effective at reducing your personal footprint would be switching to an electric car. Another study projected emissions to rise 51% from 2005-2050, and estimated that dietary changes could decrease these emissions by 29–70%.

It is important, however, to consider the air miles and environmental demands of the staple grains, nuts and vegetables of a vegetarian/vegan diet. Try to buy local, organic or sustainably-farmed produce as much as possible.

How can I cut down on meat?

Don’t get me wrong – the whole world becoming vegan overnight is not going to solve the issue of climate change. It could even be argued that being vegetarian/vegan is only treating the symptoms of the issue and not the underlying cause – in order to truly tackle its environmental impact, we need research and reform of farming practices. However, the more people turn away from meat, the more pressure that is put on agricultural producers to address these issues.

If the thought of going cold-turkey, cold-pork and cold-beef all at once terrifies you, here are some less radical ways to cut down on animal produce:

1. Meat-free Mondays

(Or try allocating weekdays/weekends to eat purely vegetarian)

- Try the Happy Pear, Jamie Oliver, Deliciously Ella for inspiration.

- Cook with lentils, mushrooms or aubergines – green/puy lentils are great as an alternative to mince in shepherd’s pie, spaghetti Bolognese etc. The meaty texture of mushrooms and aubergines work well as a meat substitute.

- Use tofu or the tastier tempeh. Available in Asian stores or health food shops.

- Buy veggie sausages for a change – Dee’s/Linda McCartney’

2. Limit your meat intake to one meal a day

- Try to reduce the amount of red meat you eat in particular

- Use substitutes like falafels, roasted veg or butter beans in place of chicken in your salads.

- Eating fish is an often called-upon method of reducing meat consumption. If doing this, please be sure to check that the fish is sustainably sourced!

3. Try non-dairy alternatives

- Almond milk has become hugely popular over the last while, but be conscious when buying it – try to .

- Making your own rice/oat milk is a cheap and environmentally-friendly alternative to dairy milk.

- Soy-based yogurts and butters don’t differ hugely in price from dairy ones – I use Pure spread and Alpro/Sojade yogurts.

- Coconut yogurt – try making it at home to save money.

- Nobo. Amazing ice-cream – and Irish! It is expensive, but that just means you learn to ration your portions instead of eating the entire tub in one go.

How can I get my protein/aren’t you anaemic/is it not really hard?

Obviously, if you’re going to cut animal products out of your diet, you have to be aware that you are losing some major protein sources. That doesn’t seem to have affected this vegan (and steroid-free) body-builder, Billy Simmonds, too much.

There are plenty of plant-based sources that can sufficiently provide you with protein. Be sure that your diet includes:

- Beans/lentils/chickpeas

- Nuts – loose nuts, almond milk, nut butters

- Seeds – sunflower, pumpkin, linseed, chia, hemp

- Dark green veg – spinach, kale, green beans

- Tofu/tempeh

- Oats, quinoa, freekeh and other whole grains

A serving size of chicken has around 25g of protein, in comparison to 18g for a portion of lentils. It may not be equal, but as long as you maintain a balanced and healthy diet, you won’t find yourself at a nutritional disadvantage.

No, I am not anaemic from lack of red meat. It is true though that a vegan diet does not include a good source of vitamin B12, a deficiency of which can also cause anaemia. Vitamin B supplements are easily purchased in health shops, and for anyone following a vegan diet, it is probably advisable to take one.

Who removed my cheese?

And no, before you ask, it is not hard at all! Vegan cooking can be adventurous and flavoursome, and it’s not difficult. You can find almost everything you need in major supermarkets and health stores, and Asian supermarkets are a gold-mine. Vegan options are popping up on menus everywhere and if you call in advance, most restaurants can cater for you. And if you feel like you might be interested in trying, but you just couldn’t give up cheese – don’t give up cheese so! There are no absolutes, and any effort is better than none.

We need both individual and collective action on climate change, even more so now that people like Donald Trump are rising to power and threatening environmental progress. So if you’re dismayed with the state of play, try changing the state of your plate. Ditch the Friesians, join the vegans and ignore Homer Simpson – you do make friends with salad, and you make a difference too.

[1] Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations, “Livestock’s Long Shadow: Environmental Issues and Option”. Rome, 2006.