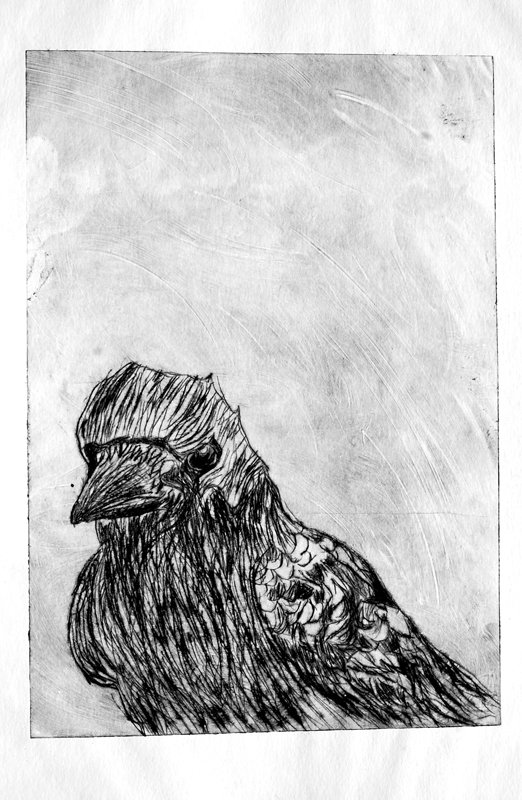

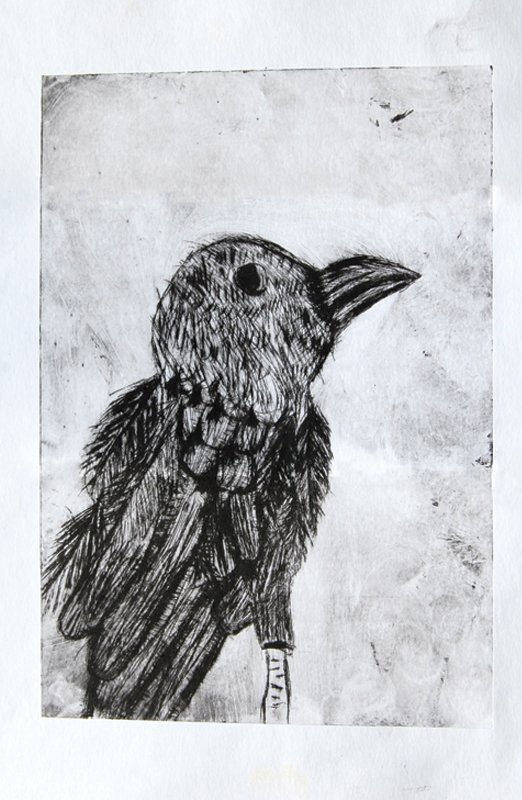

Scarecrow

Scarecrow by Alan Bennett.

Teresa plunges the colander under the warm water in the sink. An opportunistic splash dives for the disappointing freedom of her apron. It begins to dry in. A Pyrrhic victory.

She’s told herself before, ‘never let broccoli dry in the colander’. Now she has to use extra elbow grease to scrub the aftermath. She looks out the window at her husband. The comfort of his presence calms her down. Their relationship isn’t that much different now. She’s still always inside and he’s always outside. There are only two key differences between now and then. One, she makes less food and two, she doesn’t say goodnight. Otherwise it’s as you were.

She lifts the colander out of the sink, lets the water pour out like streamers. Stubborn little green broccoli balls still cling inconsiderately to the side. She puts it back in the water, more gently, lets it fill up with sink water like a shot up ship. She opens the press at her knees, takes out a Brillo pad. Time for the big guns.

That’s what he said about Tommy – ‘the big gun’.

‘Like a Tommy Gun?’ she’d asked.

‘I hadn’t even thought of that,’ her husband’d said.

She didn’t really know what he meant then, but it was too late to ask him, he’d already gone out the back door. She assumed it just meant Tommy was his right-hand man.

Brillo pads are amazing. She feels around the colander under the water. Smooth. Job done. She lifts it out again, water pours like a Co. Leitrim Bellagio. She gives it a wipe and places it on the draining board. She takes off her rubber gloves, inside out, and hangs them, dripping, over the tap.

She presses her palms down on the counter and looks over the chives on the windowsill through the glass at her hubby. He hated when she called him that.

‘It’s stupid,’ he’d said, ‘it makes one of us sound like a child, and what’s worse is; I don’t know who.’

He was always awful at making scarecrows. Or maybe they just had particularly brave crows around here. Or maybe clever. Either way, the only time the crows would leave the field alone was when he was out there making the unconvincing scarecrow. Unconvincing to a crow – his greatest shame. He wouldn’t even be fully out of the field yet after finishing the job and crows would already be landing on the scarecrow’s head, lining up on its arms. Then he’d turn back and run at them shouting and they’d scatter, but only until he was gone again.

They were never a sexual couple, himself and herself. They consummated the marriage on the honeymoon in Killarney. And they had sex a handful of times in the twenty years following that too. But neither one of them was very interested in the idea. They were more like two people keeping each other alive, propping each other up. He did outside, she did inside, they were a team and it suited them both down to the ground.

Tommy walks by the window, dragging something, doing whatever it is men do. Men always find a reason to drag or bang or kick or throw. She supposes there are just different verbs for inside work and for outside work. Hers are put, place, scrub, wipe, tidy, simmer.

Still though, it was great to have the big gun around. He was number two but he was able to step into the number one boots when it was asked of him. It meant everything could stay the same. Except she doesn’t say goodnight and Tommy feeds himself.

She tidies around the sink and the counters. She checks on her broth, simmering away nicely. She rinses her cloth and washes her hands and again she gazes out the window.

She only found out she was quite well off when her husband died. Her inheritance was substantial – the farm had been making a lot of money for years. He didn’t concern himself with money, being rich meant nothing to him. He only concerned himself with the daily running of the farm. And the crows. He came into the house one day after shouting and chasing away the birds in the field – two more outside verbs.

‘Those feckin’ crows’ll be the death of me,’ he said.

And they were. He took a fatal heart attack out in that field one summer afternoon.

She was upset. Of course she was upset. But that didn’t stop her noticing that the crows didn’t land in the field. Even as a defeated pile on the grass, her husband was a better deterrent to the crows than his miserable scarecrows.

She had a small service for him in the house and told everyone she was going to have Tommy bury him in the garden. To keep him close to home.

She did keep him close to home, but she didn’t have him buried. She had him stuffed and stood out in the field so she still has her company and there isn’t a crow in sight.

It’s what he would have wanted.