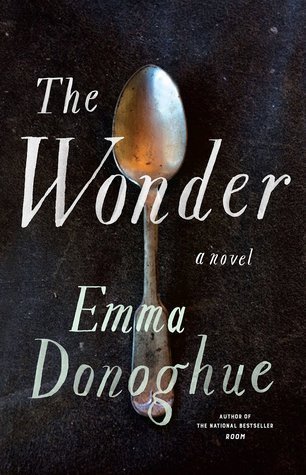

Review | The Wonder by Emma Donoghue

The first thing likely to strike any Irish reader of Emma Donoghue’s new novel The Wonder is the contempt its narrator holds for the Irish. Sure, it may be the obsessively catholic and dismally poor rural Ireland of the 1850s, but it’s hard not to see a certain analogue of today’s country in the image Donoghue paints – less a literal reflection of said attitudes and more a residual taint of their presence. Under the premise of a gripping yarn, Donoghue dares her readers to confront a damning indictment of themselves through a heightened vision of their past.

The book never makes the mistake, however, of being too obviously about a message rather than a story. For a the most part, The Wonder assumes the guise of a skewed alternative to the detective story. English nurse Lib Wright has been called to the post-famine Irish midlands to investigate the case of an 11-year-old girl who has stopped eating, but remains miraculously alive and well. It’s a classic, almost gothic, mystery setup raised to tragic proportions by the protagonist’s lack of social agency. Lib is an outsider in every sense – a rationalist protestant English woman in a patriarchal, catholic, nationalist, and superstitious Ireland. Her role is specifically to observe the case for fraud – and the closer Lib gets to an answer the more painfully aware she becomes that solving the mystery means very little, as she’s powerless to act on her discovery.

So instead, the reader is treated to scene after scene of Lib watching, only able to store up her scorn internally at the awfulness of Irish society. Thus The Wonder paints a negative and hostile portrait of 19th century Ireland, which (at least initially) verges pretty close to the Punch cartoons of the time that depicted the Irish as ignorant apes. “What a rabble, the Irish,” she muses at one point. “Shiftless, thriftless, hopeless, hapless, always brooding over past wrongs.” It should be a tough sell to make such a narrator relatable, let alone likeable, but Donoghue pulls it off. In only a few pages before the reader sees an all too familiar setting through freshly cynical eyes.

For all that, The Wonder veers far closer to a more traditional model of the Irish novel than most of Donoghue’s previous work. The point is not to echo the past but to repurpose it to a modern audience as a place that is startlingly (and as the novel progresses, horrifically), backward.

Despite this arch throwback to the past, The Wonder does in fact have a lot in common with Donoghues’ previous novel Room, and its Oscar-winning film adaptation. Long passages of the novel are once again a woman and child alone together in a single room, and this time there is no saving consolation of a redemptive familial bond. As with Room, these scenes are powered by slim exchanges of dialogue, whose surface level innocence and innocuousness belies a void of emotion, lurking unmentioned.

The horrific core of the book is an image both starkly simple and utterly heart-breaking: a starving child. Like Lib, the reader is left watching helplessly as a child hangs precariously on the verge of death, with a family and larger community too apparently caught up in their fundamentalist religious world view to take the situation seriously. Even the local doctor seems too ready to believe in a miracle, rather than recognise that the community has gathered together to offer up prayers of thanks as they watch a child slowly dying.

As with Room, this novel’s power is in its minimal yet striking descriptions. The text races though simple descriptions, scene after scene. The simplicity of the prose does not deny us the bigger picture. Even as Lib sees the Irish as a rabble of dangerously superstitious simpletons, Donoghue’s prose picks out a raw humanity in the vulnerability of an abjectly poor society still rebuilding itself from the disaster of the great famine. It’s not the individual superstitions and contradictory attitudes upon which the novel places its scorn, but rather a society which has fostered them. There’s hardly a single character in the whole novel who doesn’t appear as a richly drawn sketch of someone who, were it not for the injustice of the world into which they were born would be far better off. That Donoghue manages to suggest such texture though such deceptively bare and occasionally utilitarian prose speaks to her power as a writer.

The Wonder is a novel unafraid to suggest one direction only to suddenly shoot off in another; to build up one expectation only to catch the reader out with the tragic twist that that would have been obvious, had the reader not refused to believe it. It’s a searing portrait of people suffering through an unfair world, rendered in such a way that’s almost impossible to ignore. The Wonder invites many comparisons to modern Ireland. An Ireland that’s still content to let women and children suffer the lingering remnants of Ireland’s own brand of Catholicism. However, the humanity Donoghue wrings from her characters mean The Wonder remains a simultaneously addictive and chilling human tragedy.

Featured Image Source – emmadonoghue.com