Literature on Film |20| In Both Book and Film Jaws Remains the Best Small-Town Seaside Thriller

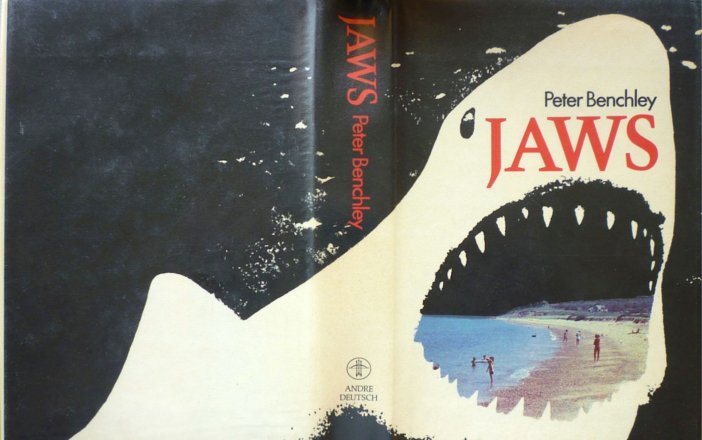

Peter Benchley’s Jaws was a mammoth success when first published in 1974, spending 44 weeks on the bestseller list and selling 5.5 million copies by the time the film adaptation was released. Yet if asked about Jaws, most people will answer based on their experience seeing the movie and not reading the novel. In many ways it’s understandable, Jaws is one of the most satisfying, terrifying and enjoyable films ever made and it just happens to be my personal favourite, a film I watched for the first time when I was probably just a little too young. I was in the 6 or 7 year-old bracket and my older sister and I convinced our elderly babysitters that it was okay to watch this “giant fish film” as my father called it (our parents were out at a now defunct social engagement popular in the 1980’s – the dinner dance). To say it changed my life may be a bit of an exaggeration but the memory of viewing it for the first time never left me; the panic and fear are as real to me now as they were then. When I was about sixteen I found myself staring at the cover of Peter Benchley’s Jaws in a second hand bookshop in Wexford town, priced at the princely sum of 80p. I made it mine. At that stage, after numerous viewings, I felt it was time to read the source material.

At 285 pages, Jaws is not a taxing read and proves as page turning a read as Spielberg’s film is absorbing a watch. Yet Benchley’s novel bucks an accepted trend, it is most definitely not better than the film. While both deal with the same subject matter, the novel and the film are very different, especially seen in how both Benchley and Spielberg treat their characters. Police Chief Martin Brody, ichthyologist Matt Hooper and the seasoned sea captain Quint are written quite differently in the novel to those that we are familiar with from the film. The greatest changes can be seen in both Brody and Hooper. Sadly both men, Hooper in particular, are quite hard to like. Benchley’s Brody is a sullen, jealous husband. Hooper is a charmless WASP. As the novel progresses Brody becomes more and more suspicious about Mayor Vaughan’s reasons for keeping the beaches open, about who Vaughan’s “partners” are and whether his marriage is disintegrating or not. Also, the great conflict that characterises Spielberg’s Brody, namely the fact that he is an ex-NYC cop with a fear of water who decides to live on an island is not present in Benchley’s novel. Benchley’s Brody is a born and raised Amity resident with no water hang-ups. Instantly the audience find themselves at a distance from this Brody, his presence on the Orca in the novel does not elicit the basic emotional response that it does in the film. The moment Brody sets foot on the Orca, just after instructing his wife to tell his sons he’s “going fishing” is the very moment the film’s audience embraces Brody as the hero.

Benchley’s Hooper displays probably the biggest change from novel to film. In the film Hooper is charming, affable and extremely likeable. In the novel Hooper is a slick, arrogant and often obnoxious young man, a character defined by his wealth. Why this contrast? It may be, in part, down to how Benchley wrote Ellen Brody. In the novel Ellen is a former New York socialite, a WASP herself who falls in love one summer with an older man, a policeman. Wintering in New York City and summering in Amity was the norm but she gave that up and moved to Amity full-time, married her policeman lover and had three children with the now Chief. Yet when we meet them in the novel the Brody marriage is starting to unravel, with Ellen missing the razzmatazz of New York City. In Hooper she sees an escape and so begins a sexual affair with Hooper. Yes, Ellen Brody cheats on the Chief.

As written by Benchley, Hooper’s only real contribution to the novel is to awaken this yearning in Ellen and to satisfy a sexual craving. Yet the preamble and eventual sexual encounter itself is quite unsettling as during the 20 odd page seduction sequence, Hooper asks her about her fantasies. This is the conversation shared by both, just edited from a full page to a few lines: “’To fantasies,” he said. ‘Tell me about yours.’…‘Oh, you know,’ she said. Her stomach felt warm, and the back of her neck was hot. ‘Just the standard things. Rape, I guess, is one.’ – ‘How does it happen?’… ‘I let him in the door and he threatens to kill me if I don’t do what he wants.’ – ‘Does he hurt you?’… ‘No. He just…rapes me.’ – ‘Is it fun?’ – ‘Not at first. It’s scary. But then, after a while, when he’s…’ – ‘When he’s got you all…ready.’”

I mention it to highlight how totally different Hooper is in the novel than in the film. Novel Hooper is a brash, over-confident and often odious character who seems very much redundant after the affair as he contributes very little to the hunting party except his presence being a constant barb in Brody’s side. His character is so much in the deficit column towards the end that the only thing Benchley can offer to try make his readership empathise with him is death. One of the massive structural changes from novel to film is Hooper’s killing by the shark in the penultimate chapter, quite graphically described by Benchley, “The jaws closed around his torso, Hooper felt a terrible pressure as if his guts were compacted…The fish bit down and the last thing Hooper saw before he died was the eye gazing at him through a cloud of his own blood.” Benchley’s Hooper did not endear himself to the reader and the only sympathy the reader draws from his death is the manner in which he dies.

Then there was Quint. His salty, cantankerous nature and colourful language are all present in both novel and film but Spielberg’s two-hour film adds far more depth to the character than Benchley’s novel. As written by Benchley, Quint is not just irritable and moody but actually mean, to the point of being evil. In the novel he keeps dead baby dolphins as prize chum to entice the shark. He also catches smaller sharks, hooks them up to the boat and then slits their bellies open, the gore inviting other sharks to the boat to feed, taking pleasure in watching the eviscerated shark attempt to eat his own entrails. In the novel there is no “All know me, know how I earn a living…” speech, no “Just tie me a sheep shank…” sounding-out of Hooper and his seafaring ability and most importantly no Indianapolis speech. Benchley does attempt a very brief motivational back-story for Quint, glancing over a titanic struggle he had once with a 15-foot Great White while on a fishing charter; but you haven’t journeyed with him, you haven’t disliked, then respected, then feared this Quint. For all his bluster, he seems very much like a collection of sea shanty stereotypes.

The comparisons with Ahab go without saying – both men are driven to kill their ocean nemesis, willing to risk not only their own lives but also those of their crew in achieving this goal. A trailing line from Ahab’s harpoon drags him to his death behind Moby Dick, a coiled rope from Quint’s harpoon snags his foot and the shark drags him into the sea depths. Quint’s death in the novel is nowhere near as dramatic or, if I may say, satisfying. Quint’s maniacal and morbid determination to destroy the shark can only be matched by the shark’s determination to destroy him as it so gruesomely does in the film. In the novel the shark dies of exhaustion, spent from the exertions of battling the barrels harpooned to him, slipping backward in to the dim gloom of the ocean – “The fish was nearly touching him, only a foot or two away, but it had stopped. And then, as Brody watched, the steel-grey body began to recede downward into the gloom…The fish faded from view. But, kept from sinking into the deep by the bobbing barrels, it stopped somewhere beyond the reach of light, and Quint’s body hung suspended, a shadow twirling slowly in the twilight.” As beautiful as that paragraph may be, I’d take “Smile you sonofabitch” over it any day.

Isolation is one of the key features of Spielberg’s film, exampled by the second half, which is set entirely at sea. Spielberg goes to great lengths to highlight the separation between the three ship-bound men and dry land. The Orca never returns to Amity after it sets out, Quint destroys the radio and only towards the climatic pursuit between shark and boat is the coastline seen. In Benchley’s novel the Orca returns to harbour each night and so removes one of the most intriguing and interesting aspects of Spielberg’s film – the grudging respect and bond that develops between the three men. While Benchley’s novel does not feature the Indianapolis speech or anything on a par to replace it, it also does not offer anything as binding and revelatory as the after dinner conversation where they “drink to their legs.” Quint’s criticism of Hooper during their first meeting, the “You got city hands Mr. Hooper. You’ve been countin’ money all your life” speech, is counterbalanced by Quint’s gradual warming-to and eventual acceptance of Hooper’s tech heavy methods to capture and kill the shark. Once he realises that the Orca is doomed to founder he asks, “Hooper, what exactly can you do with these things of yours?” This Quint, as he calmly and methodically inspects Hooper’s items, is no longer in control, which is quite a reversal as during his most colourful outbursts and frenetic attempts to harpoon the shark with barrel after barrel he is like a man possessed yet a man in total control. Once he realises that the Orca is sinking he exudes a calm and a resigned bravado – this Quint knows he is going to die, conveyed in his passing of life jackets to Hooper and Brody without donning one himself, a recognition of the fate that escaped him on the Indianapolis has just caught up with him. In that one moment we see Quint accept that he is wrong, something that Benchley’s novel doesn’t attempt as this Quint is not his Quint. This is the key feature and the chief deficiency of the novel toward the film, Brody, Hooper and Quint are Spielberg’s characters and not Benchleys, Benchley may have created them but Spielberg loved them.

[youtube id=”U1fu_sA7XhE” align=”center” autoplay=”no” maxwidth=”750"]

Yet one character of all is truly loved by both Benchley and Spielberg – the shark. Known only as “the fish” throughout the novel, it appears only a handful of times before the prolonged hunt aboard the Orca. Initially the fish is depicted not as an evil creature; the fish is simply an animal feeding to survive. It doesn’t kill for sport like the dinosaurs in Jurassic Park or the lions in The Ghost and the Darkness, the shark is hunting only for food; but once the Orca is introduced the shark’s motivations change. Not trying to invest in the fish a personality, but it attacks the Orca with the zeal of a person wronged. It is relentless and methodical, trying for weaknesses, attacking the boat’s hull or chewing through the lines keeping it from staying under the surface of the water. These little intricacies put the three men on the back foot, perfectly captured by an exchange of the same line, the same thought, from Brody to Hooper and then Hooper to Quint – “Have you ever had one do this before?” The answer from Hooper to Brody and, more worryingly from Quint to Hooper is the same, a simple “No.” Almost immediately the crew of the Orca go from hunters to hunted.

In the novel there is no hero where in the film Spielberg earmarked Brody for that role. He takes on the shark, not with hooks and lines or portable anti shark cages or potent poisons but with a rifle, a cylinder of compressed air and a little bit of guile. With the Orca listing sickeningly, the mast of the Orca slips closer and closer to the waterline, into a perfect biting position. In that moment, as Brody takes aim at the cylinder of compressed air the audience held its breath. Spielberg had us in the palm of his hand. Benchley, unfortunately, did not. His Brody does nothing in the climax to elicit such an emotional response. His Brody is not a hero, he is just the only survivor of the Orca. His Brody didn’t conquer a fear or achieve anything.

The differences between the novel and the film of Jaws are vast. While the film is not massively structurally different it is totally so in terms of tone and characterisation. Though first published and theatrically released a little over a year apart both versions can be characterised by how kind time has been to them. Jaws the novel was a 1970’s potboiler, a curtains-twitching small-town thriller. Jaws the film is an adventure, a timeless example of lean, taut story telling. Yet without Benchley’s novel we would never have had the film and regardless of which is better we owe Peter Benchley a debt of gratitude. We owe Steven Spielberg our fears. In the The Shark is Still Working documentary Spielberg himself recalls an encounter with a harried mother and her young son on the beach one day in the late 1970’s. He wasn’t asked but accused of being Steven Spielberg and when he admitted he was she dragged her young son forward, “Tell him. Tell my son that Jaws was only a film and it’s okay to go swimming in the sea.” With a knowing grin he knelt down to talk to the boy and couldn’t help but admit, much to the mother’s chagrin, that there are monsters in the deep and there could very well be a shark out there before walking away, no doubt smiling and dah dah dumming to himself. At some stage weren’t we all that child, standing at the edge of the waterline wondering is it out there? I know I was.