William Corder, the Red Barn Killer

William Corder was born in 1803 in the village of Polstead in Suffolk, England. His father John was a well-off farmer, though as his second youngest son William wasn’t expected to inherit the farm. His father made sure that he didn’t forget it either, and frequently made William the target of his abuse and insults. William attended the local school followed by three years at a private where his mixture of intelligence and slyness got him the nickname of “Foxey” Cooper. He showed some talent for writing, and had hopes of a career as a journalist or a teacher. His father had no intention of financing this though, and instead William had to return home to work on his father’s farm.

Legend has it that William was involved in much petty criminality during this period, though whether this was due to rebellion on his part or due to his father’s tendency to place the blame for anything that went wrong on his shoulders is hard to say. His alleged crimes included selling his father’s pigs without license to do so, and passing a forged cheque. Some of this may be stories created after William became infamous, but his conduct was bad enough that his father exiled him from the farm and sent him to London to join the Merchant Navy. William failed the physical examination due to poor eyesight, but rather than return to Suffolk he decided to stay in London and see if he could manage to live independently. This was probably the first of many mistakes that set William’s course.

Like many young men kept under tight constraint at home, William’s trip to London led to him running wild. In the course of his debauchery he became acquainted with a former actress turned prostitute named Hannah Fandango. Hannah was actually from William’s neck of the woods, as she had connections to a smuggling ring that ran goods through the Polstead area. The leader of the gang, who Hannah introduced William to, was a man named Sam Smith but generally known as “Beauty”. It’s likely William knew him by reputation – in fact, an alternate history of events has William helping Sam steal a pig in Suffolk and that being the reason for his banishment to London. If this were true, then it’s likely that William introduced him to Hannah and not the other way around.

William’s attempts at finding an independent living failed, and his father allowed him to return to Suffolk in the April of 1825. The following winter both William’s father John and two of his brothers became ill with tuberculosis. The two younger men survived, though their health was destroyed and they became permanent invalids. John Corder, William’s cruel father, died. His eldest son Thomas inherited the farm, and with William the only other able-bodied male in the family his status and freedom naturally rose. This allowed him once again the chance to indulge his appetites, and his roving eye fell on a young woman named Maria Marten.

Maria was in many ways an unfortunate victim of the sexual double standard that was firmly in play in Victorian Britain. Men were encouraged to sleep around, while women were shamed for doing so. In London this led to the city’s flourishing sex trade, where men preyed on women stigmatised for selling themselves not through choice but out of poverty and despair. In the countryside the same stigma existed, though on a much less industrial scale. Maria had been cast in the role of “good girl”, having been hired into the service of a clergyman in nearby Layham at a young age. When she was fifteen she was dismissed for “levity of behaviour”. At the age of nineteen, she had borne an illegitimate son with William’s brother Thomas. Her father made a living catching moles and turning them into gloves – a position far down the social scale from the land-owning Corders. In contrast to William, Thomas was old John Corder’s favourite son and so the whole thing was all hushed up – something which became easier when the infant died, as so many children did at that time.

Maria cemented her position as a minor village scandal by bearing a second illegitimate child, this one the son of a member of the “landed gentry” named Peter Matthews. The pair had met at a village fair in Polstead, when Peter was visiting the local squire. [1] Their affair went on for some time but abruptly ended when Maria became pregnant, with Peter agreeing to pay an upkeep for the child in return for her absence from his life. Young Thomas Henry became part of the Marten family, which also included several other young children – Maria’s father Thomas Marten had remarried to a woman named Ann who was not much older than Maria.

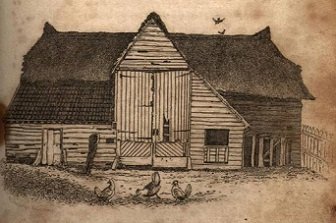

Popular legend has it that William and Maria kept their affair secret at first, and so many of their encounters took place in discreet and remote locations. One such was the Red Barn – probably so-called due to its roof being partially made of red brick tiles. Later events led to the barn’s name being given a much more sinister origin but in truth it was just one among many such buildings dotted around the farm, named for its single memorable feature. They soon moved their affair into the open though, as William gradually began to lose his fear of his dead father. Maria’s family became aware of the relationship and may even have encouraged it – William’s new position as de facto deputy of the Corder farm was enough to make him a fairly good catch for Maria, while still leaving him within her reach.

In the autumn of 1826 Maria realised she was pregnant again and told William. His initial response seems to have been to panic and try to conceal the pregnancy, but once he realised that it couldn’t be concealed he went to Maria’s parents and told them that he would marry her once the child was born. Before that, events overtook them once again. In February of 1827, during the hard Victorian winter, Thomas Corder took a shortcut across a frozen lake on his way home from a friend’s house. The ice cracked, and Thomas went through. He died. All of a sudden William was now the owner of the Corder farm.

The stress of this sudden responsibility seems to have taken its toll on William, especially as the farm was doing poorly financially. Maria gave birth to their son in March, but the child died within two weeks of its birth. Maria, too, was weakened and left seriously ill by the difficult birth. William persuaded her and her parents to hush up both the birth and death, and he and Maria secretly buried the child. He assured them that he would marry her, but he seems to have been getting more and more nervous about the whole thing. Furthermore it was rumored that the local parish officers were planning to arrest Maria for having illegitimate children – a crime punishable with public whipping. William wanted to keep it all a secret though, and arranged that the pair would meet at the Red Barn before heading off to nearby Ipswich to be married.

A few days later William returned to Polstead – alone. He told Maria’s parents that there had been problems with the marriage license, and that Maria was staying in Ipswich until they were resolved. Days turned into weeks, however, and William stayed on his farm with no sign of Maria. The death of William’s two sickly brothers kept him too busy for the Martens to bother, and once that was all settled he told them that he was going to go meet Maria on the Isle of Wight, where she had gone on holiday to recuperate from her illness. He left, and on the 18th October they received a letter telling them that he and Maria had finally got married. The new couple had decided to sell the farm and would be setting up a new business in Newport. That was the last they heard from their putative son-in-law.

All through the winter Ann Marten suffered terrible dreams. Local legend now says that she had always had a touch of “the sight”. She didn’t remember the dreams until the April of 1828, when on three successive nights she awoke convinced that her step-daughter Maria was dead and buried under the floor of the Red Barn. Her intensity was enough to convince Thomas, and he went to the bailiff running the farm for William to get permission to look around the barn. At the spot Ann had told him, they found disturbed earth. William stuck one of his mole-catching spikes into the ground. When he pulled it out, the decomposing flesh on the end was enough to to call in more men and dig up the barn. There, right where Ann had dreamed it, was the corpse of Maria Marten. She had never left the Red Barn.

At least, that’s the most popular version of the story. The more sceptical might point out that it would have only been natural for them to be suspicious of William, and that the Red Barn was the most obvious place to look for Maria. (A witness later said that he saw William bringing a pickaxe into the barn at around that time.) Other versions of the story have Maria’s ghost appear to Ann in her dream to point out the grave. Some accounts say that she was not buried but was instead found in a grain bin – a ridiculous idea as she would have been found there at some point in the previous year. The cause of death was also unclear – the advanced state of decomposition and the primitive state of forensic medicine at the time meant that she could have been shot, stabbed or strangled. (It didn’t help that the “stabbing” injuries could have been caused by the mole-spike.) Regardless, William was the clear and obvious suspect and a search for him soon began.

He was soon tracked down to Brentford in London. The most common story is that he was running a boarding house there, though some accounts say that he was acting as a headmaster at a local girl’s school. Most surprisingly, though, was that he was actually married – though obviously, not to Maria. William had got his new wife through an advertisement in the Sunday Times, where he described himself as “entirely independent”. He had received over a hundred replies, and from them had selected a schoolteacher named Mary Moore. They had gotten married in December of 1827. William was arrested, but denied all knowledge of Maria’s murder. A search of his house found both pistols and a passport for travel to France, indicating that he might have planned to flee the country.

The “Red Barn Murder” soon began to generate a lot of public interest. Maria’s funeral on the 20th April attracted hundreds of people, while the Red Barn (once the police had finished their investigation) was practically torn to pieces for souvenirs. The story combined several parts that made for sensational press coverage – murder, the supernatural and of course the sexual element, backgrounded enough to keep the coverage non-scandalous but still permeating the entire case. Several plays and books based on th case were rushed out during the months after the arrest. The trial (held in Bury St Edmunds, the capital of Suffolk) was originally scheduled for the end of July, but had to be pushed back to early August due to the difficulty of finding unprejudiced jurors after the extensive prejudicial coverage of the case. The crowds seeking to attend the trial were so great that every hotel in Bury St Edmunds was full, and entry to the trial was by ticketed admission. Still enough people managed to wangle entry that it was a real struggle for the judge and jury to get to their seats in the courtroom.

The prosecution’s case was that William had never wanted to marry Maria. They pointed to his previous criminal connections, and claimed that Maria was blackmailing him into marrying her. Their reconstruction had William shoot Maria, and then stab her to finish her off. Their star witness was Ann Marten. She didn’t speak about her dreams, though the papers gave them plenty of coverage. Instead she spoke to William and Maria’s relationship and departure from Polstead, as well as the behaviour of William afterwards. Maria’s younger brother George was also a key witness, as he told the court of having seen William’s loaded pistol before the murder. William’s defence was that Maria had killed herself in the Red Barn after an argument, and that he had panicked and concealed the corpse. Perhaps anticipating this he was additionally charged with eight other counts, including forgery. They needn’t have bothered. It took the jury only thirty-five minutes to find William guilty.

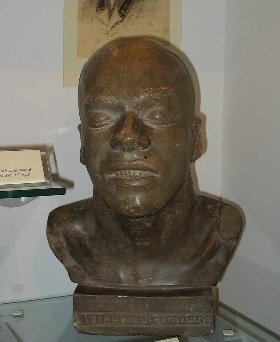

Death sentences were swiftly carried out in those days, and only three days later William was on the scaffold. In the interim he had made a confession, though he still denied having murdered Maria. Instead he claimed to have accidentally shot her during an argument. He denied having stabbed her, though. He might have been telling the truth, but at that stage it didn’t matter. He died before a huge crowd (between seven and twenty thousand, depending on reports), and his body hung there for an hour before it was cut down. Afterwards it was exhibited (with the stomach sliced open) at the county hall, where five thousand people cued up to file past. A death mask was made, and the next day the body was dissected before an audience of students.

Interest in the case did not end with William’s death. A broadside (a one-sheet newspaper-style account of the trial and execution) by the printer James Catnach sold over a million copies. The hangman sold pieces of the rope for a guinea each, while one of Corder’s ears attached to his scalp (scavenged from the autopsy) was put on display in Oxford street. A lock of Maria’s hair was auctioned off, while her gravestone was destroyed by souvenir hunters chipping pieces off. William’s skeleton was originally meant to be a teaching aid at a hospital, but was soon repurposed as a fund raising tool. The skull was bought (or possibly stolen) and replaced with another skull by a rabid collector of Red Barn memorabilia named Doctor John Kilner. (He had already acquired the ear and scalp.) The story goes that after he took the skull he had a run of bad luck and uncanny incidents that led to him finally giving it a “Christian burial”, though where he found a priest willing to bury a skull is not stated. The scalp wound up in Moyses Hall Museum in Suffolk, along with a book (containing an account of the murder) bound in Corder’s skin. The skeleton (possibly with ersatz skull) eventually was put on display at the Hunterian Museum in London, hanging next to the skeleton of Jonathan Wild It was taken down and cremated in 2004 after a descendant of the Corder family made an appeal to the Royal College of Surgeons.

The Red Barn story became a staple of Victorian “true crime” literature, though it was gradually distorted over time to make William a more perfect villain and Maria a more perfect victim. He became a country squire, no longer her junior but instead a typical lecherous old man, while her earlier children were quietly swept under the carpet. The fact that he was actually two years younger than her also was often changed. Naturally, the story became the inspiration for films in the 20th century. A 1935 version was based on the Victorian melodramatic style and proved, in its first cut, too violent for an American release. Several more film versions followed. In 1967 a British journalist named Donald McCormick wrote a book that dove into William’s criminal past and claimed that it was actually “Beauty” Smith who had murdered Maria in order to prevent her revealing his and William’s smuggling operations. [2] Later researchers decided that McCormick had at best read too much into his sources and made too many assumptions, and at worst had made his story up out of whole cloth. [3] Another famous modern book on the case, by the the journalist and anthologist Peter Haining, played up the occult element and suggested that locals may have feared Maria was a ghost or vampire of some kind, though his evidence for this is scant at best. Still, with songs, films, books and documentaries based on the Red Barn murders still coming out (the most recent in 2015), it seems that William Corder, Maria Marter, and the Red Barn Murder remain as fascinating to us as they did to the Victorians.

Images via Murderpedia except where stated.

[1] Later legend would paint the Corders as the squires of the area but they were simply well-off independent landowners. The local squire was actually a woman named Mary Cook.

[2] There’s also a theory that Ann Marten killed Maria out of jealousy, but this seems to be based entirely off gossip at the time caused by her young age relative to her husband.

[3] McCormick had form for this sort of thing – for other examples I recommend Mr Jim Moon’s podcasts on the Lower Quinton Murders and the Case of Bella In The Wych Elm where he thoroughly deconstructs McCormick’s writing about those cases.