William Randolph Hearst, the Original Media Mogul

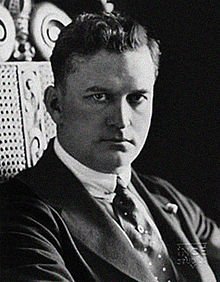

William Randolph Hearst was born in San Francisco in 1863. His father George was a former Missouri farmer who had come to California for the gold rush, but had been smart enough to see the money to be made in quartz and silver mining as well. Silver mining had made George a multi-millionaire by the time young William was ten years old. William’s mother Phoebe had grown up with George, and when he returned to Missouri to care for his sick mother the pair reunited. William was their only child, and with George absent first on business and then later with a political career, it was left to Phoebe to raise him. He was sent off to a boarding school in New Hampshire in his teens, and then went to Harvard for two years. There he had an active social life, as well as getting involved in various side activities. Most notably, he was on the staff of the Harvard Lampoon, his first taste of the publishing business. He left Harvard without getting a degree however. He was infamous for his pranks – he was said to keep a pet alligator in his rooms who was nicknamed “Champagne Charlie”, and to have once smuggled a donkey into a professor’s room with a label saying “Now there are two of you”. The final straw was when he sent all the members of the senior faculty chamber pots with either their names or images drawn inside (reports vary). This was seen as a step too far, and he was packed off back to the west coast in disgrace.

The 24-year old Hearst was left casting around for something to do, and settled on “borrowing” one of his father’s acquisitions. George had bought the San Francisco Examiner in 1880 (or possibly received it to settle a debt) and had mostly used it as a political mouthpiece and nothing more. It had been failing even before than, and only George propping it up had saved it from total collapse. Since George had already been elected to Senate he didn’t really need the paper any more, so he cheerfully gave it to his son in the hopes that it would keep him out of trouble. It would later become clear that George was never hugely impressed by William.

Hearst immediately redesigned the paper in order to signal that a new era had begun. A flashy new logo and a grandiose motto, “The Monarch of the Dailies!”, set the tone nicely. The main thing Hearst brought to the paper, though, was money. San Francisco was home to some of the most famous writers in America: Jack London, Ambrose Bierce and Mark Twain being the standout names. Hearst hired all three, and they brought in readers. He also fostered talent, hiring the young cartoonist Homer Davenport from a rival newspaper at almost double his previous salary. But it wasn’t just money that Hearst brought. He also brought focus. Hearst targeted his newspaper directly at the lower classes – the San Francisco working men (specifically men) who distrusted authority and had scant interest in facts when a sensational story came along. Hearst made his bones with stories of corruption, and won a great deal of respect for not exempting his family’s businesses from his exposures. But though Hearst took the Examiner from failure to success, it was always only a stepping stone for him. He wanted to go national – and in America, if you want to go national you do it in one place. New York City.

As with San Franciso, he broke into New York in 1895 by buying a failing newspaper, the New York Morning Journal. This time it was purchased for him by his mother, rather than his father. George had died in 1891 and had left the bulk of his fortune to Phoebe. Though she was generous to William she didn’t give him a blank cheque. But his success with the Examiner convinced her this could be a wise investment, so she signed the papers and the Journal became a “Hearst paper”. That was the first step, but New York would soon prove a harder nut to crack than San Francisco.

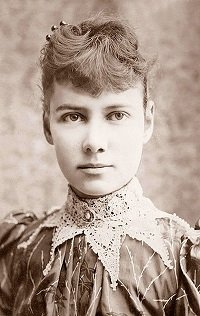

Hearst’s main competition was a man whose tactics had been his inspiration at the Examiner – Joseph Pulitzer. [1] Pulitzer owned the New York World, and had made it one of New York’s best selling papers through a combination of publicity stunts (such as sending ace reporter Nellie Bly around the world in 72 days) and hard-hitting investigative journalism (such as sending ace reporter Nellie Bly undercover in a woman’s mental asylum). Pulitzer also exposed the deadly conditions in New York tenements, though it was his more sensational stories that his rivals highlighted and that became the reputation that stuck.

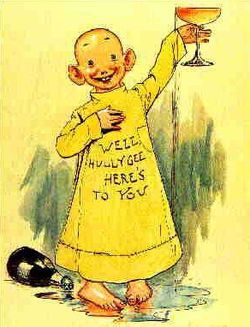

Hearst made it his mission to beat Pulitzer at his own game. Since advertising was where the real money was, and circulation was just a way to drive those advertising prices up, Hearst sold his paper at a penny – though it was as thick and dense as the two-penny World. In response, Pulitzer cut his own price to a penny. Hearst’s counter was to go after Pulitzer’s talent. In 1896 Pulitzer became the first publisher to include a colour supplement on Sundays, and to many the page of cartoons he included was the highlight. The most popular was “Hogan’s Alley”, by Richard F. Outcault. This was a satirical cartoon featuring Mickey Dugan – the “Yellow Kid” – targeted at adults. Hearst hired Outcault away, though Pulitzer soon replaced him. As a result both papers wound up with their own versions of the “Yellow Kid”.

It was due to this that the pair of papers became referred to by those who considered themselves above reading them as “the Yellow Kid papers”, and the style of reporting they did thus became “yellow journalism”. Sensational, unapologetically aimed at the working classes, and not above making a few things up to sell papers. The peak of their rivalry came with the Spanish-American War. There’s a story that Hearst sent a war artist to Cuba, who telegraphed back home that all was quiet. Hearst is famously supposed to have sent back:

Please remain. You furnish the pictures and I’ll furnish the war.

It’s a good story, and a great quote, but sadly there’s no evidence that it ever actually happened. Hearst definitely did do a great deal of pushing for American intervention in Cuba though, running many stories about Spanish villainy and the heroism of the rebels. One of the best-known was the story of Evangelina Cosio, daughter of an independence activist. When her father was taken prisoner by a governor, Evangelina’s appeal for his release resulted in her being assaulted by the governor, rescued by her friends and then charged with attempting to murder him. Hearst heard her story and while she was in jail awaiting trial made her a celebrity, getting a petition with 15,000 signatures to have her released. After it became clear this would have no effect, Hearst sent a reporter named Karl Decker to Cuba to break her out of jail. Decker succeeded, and Cosio was smuggled back into America. There Hearst held a reception for her in Madison Square Gardens, had her introduced to President McKinley, and helped her raise funds for Cuban independence.

America did wind up involved in the Cuban war (after an explosion on an American warship, probably accidental, was blamed on Spanish saboteurs). Hearst went to Cuba in person, with an army of reporters, to cover the war. They fitted a yacht, the Sylvia out as a mobile newspaper office complete with printing presses and a photographic darkroom. They were so well prepared that they actually arrived in Cuba before the US army. It might have seemed like a jolly jape to some, but Hearst took it all very seriously. Perhaps conscious by proximity of the seriousness of it all, his war coverage was far less florid than usual. Still, he was still Hearst. On one notable occasion he was chastised by American marines when his reporters boarded a surrendering Spanish ship before the marines had a chance to. In Hearst’s own account:

‘Can’t you mind your own business?’ said the officer.

‘Not very well sir, and be good newspapermen.’

On another occasion Hearst himself captured twenty-nine retreating Spanish sailors; or rather he rescued them after their lifeboat capsized and then wound up with them on his hands as prisoners. It was this type of incident that earned Hearst a great deal of respect for his patriotism, which in the end was the greatest asset he got from the war. On the financial side, though it boosted circulation it also depressed advertising, so the whole thing resulted in the papers losing money. (The dip in circulation after the war also prompted the newsboys of New York to go on strike, which also wound up costing him money. [3]) As a result Hearst and Pulitzer quietly decided on an end to their circulation war, and both settled into an uneasy truce.

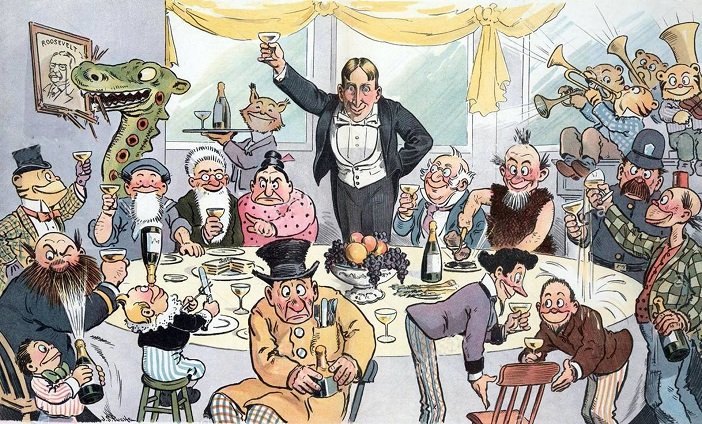

Following the end of the war, Hearst did his best to transfer his newfound popularity into political capital. He was 35 – old enough to be taken seriously, young enough that he could take this career all the way to the top. In this, as in the newspapers, he found inspiration in a rival. Last time it had been Pulitzer, this time it was Teddy Roosevelt. Both were Harvard boys, and when Hearst looked at Roosevelt’s political successes he saw a path that he could also follow (though he personally despised Roosevelt). His initial goal was pretty lofty – getting himself onto the Democratic ticket for the 1900 presidential election as vice-president. Luckily for him he had something the Democratic party desperately needed – the press. All the papers in the mid-west were under Republican control, so in exchange for Hearst starting a sympathetic paper in Chicago they offered him a position in the Democratic party. He didn’t get the vice-presidential nomination he wanted, [4] but he did get the support of the Democratic machine. Tammany Hall [5] got him into Congress for New York in 1902.

Hearst’s political career was marred by controversy from even before his first election. His papers had been ceaseless in attacking President McKinley, and one notorious editorial had even mentioned that sometimes assassination was the only way to get rid of bad leaders. When McKinley was assassinated, even though the assassin couldn’t even read English the rival papers still took the chance to put the boot into Hearst. Roosevelt (who now became president) also labeled Hearst (privately) as an “accessory to the crime”. Though the deep-laid connections and electoral manipulation of Tammany Hall got him into Congress twice, the damage done in 1901 was enough to see him fail to become mayor of New York twice, and state governor once. He made a breif foray into backing third[party candidates, but by 1909 his political career was dead in the water.

The one thing that Hearst was left with after his brush with politics was a wife. Millicent Wilson had been his mistress for five years when they were married in 1903. She was connected in to Tammany Hall – her mother ran a brothel for them. Hearst’s mother (who still controlled his finances) was not impressed by his marrying “below his station”, but Millicent soon won her over. The pair had five children (all boys), the last of them in 1915. A few years later, Hearst met the woman who would be the love of his life – Marion Davies.

Marion’s father was a New York judge, but she always wanted to get into show business. In 1916 she became a chorus girl in the “Ziegfield Follies”, a long-running New York theatrical revue that had been the launching ground for many a career. In 1917, at the age of 20, she appeared in her first film – a comedy called The Runaway Romany which she had written herself. It was good enough to get her more comedy roles, and she soon became a star. And then Hearst came along. After the two began their affair Hearst decided to get into the movie business, founding “Cosmopolitan Productions” as a movie-making branch of his magazine business. [6] Naturally, the main purpose of this was to create films for Marion, which he heavily advertised in his papers. As a result she became very famous and well-known. It was in a sense the ruination of her career though – she had been a very good comic actress, but as a dramatic leading lady she generally failed to impress the critics.

Hearst’s mother Phoebe died in 1919, and the family fortune finally passed into his hands. Without the need to follow his mother’s morals any more, Hearst moved to the family estate in California and Marion moved there with him. Millicent stayed in New York. Though the pair never actually divorced, her marriage to Hearst was effectively over. In California he began work on La Cuesta Encantada – “the enchanted hill”. This was a gigantic castle-like mansion (nowadays known as “Hearst Castle”) that connected to Los Angeles via a privately-owned train. It became a popular retreat for the invited elite of Hollywood in the 1920s and 1930s, with a guest list that reads like a “who’s who” of the era. In addition, politicians like Calvin Coolidge, Franklin Roosevelt and Winston Churchill came to visit the man who was still the most powerful press baron in America.

One such guest was Thomas Ince, a powerful film producer who had founded Hollywood’s first major studio facility. He and Hearst were discussing a business deal when he visited in 1924. On the 16th November Ince joined Hearst and several other guests (including Marion Davies and the actor Charlie Chaplin) on board Hearst’s yacht, the Oneida. The purpose (if the Hollywood elite ever needed a purpose) was to celebrate Ince’s 44th birthday. At dinner that evening Ince became ill, the result of eating foods which disagreed with his stomach ulcers. The stress on his system started causing him heart problems, so he was taken off the yacht and transported by train to Del Mar for treatment, then home to Los Angeles. He died there with his wife and eldest son by his side.

The sudden death of such a powerful man on Hearst’s yacht was always going to raise eyebrows. One paper initially reported the death as due to a shooting, and though they immediately withdrew the story it was enough to set the rumor-mill going. Soon people were spinning entire narratives out of thin air – one story was that Hearst had tried to shoot Chaplin for sleeping with Davies but had shot Ince by mistake. Though both Hearst and Ince’s family denied all these rumours, and no actual evidence ever surfaced, to this day the events on board the Oneida remain the source of stories and speculation.

Though Hearst’s politics had been mostly left-wing all his life, and he had backed Roosevelt for the presidential nomination, for some reason in the mid-1930s he underwent a radical re-alignment. Suddenly Hearst (now in his 70s) turned on the president and began to run stories denouncing him. This may have been tied to he (like many America elites) finding himself in sympathy with European fascism. In 1934 he had traveled to Germany to interview Hitler and had covered him with relative hostility, but within a few years his papers were running op-eds written by Hitler and Goring without any opposition. Quite what triggered this dramatic change in views has never really been explained. It did turn out to be incredibly badly timed, though. The shift in politics drove readers away from his papers just as the Great Depression hit. Hearst’s big secret had always been that his papers never actually made money – they had been subsidised by his investments and other businesses. With that money supply cut off, and with circulation plummeting, the whole enterprise turned out to be quite literally a paper tiger. In 1937 a court ordered a reorganisation of the company to pay its debts, and Hearst lost sole control. Though World War II saved the company, it was never again Hearst’s private empire.

The debts also compelled Hearst to sell a lot of his own private property. He was even forced to pay rent on Hearst Castle. He still had editorial control over the papers, though his anti-war “America First” stance hurt his public standing even further. Another blow to his reputation was the 1941 release of Citizen Kane. While Orson Welles was filming his masterpiece he managed to hide the fact that it was in essence a “roman à clef” [7] about Hearst. However the secret leaked just before release, and Hearst was furious. His papers attacked both the production and Welles, while his intimidation ensured that many distributors refused to pick it up. As a result the film was a critical success but a commercial failure, and it wasn’t until the 1950s that it was recognised as one of the greatest cinematic achievements ever.

America’s entry into World War 2 was the final nail in the coffin of Hearst’s career, as his refusal to condemn Hitler saw him regarded more and more as a crank. In 1943 he was replaced as president of the Hearst Corporation, and in 1947 ill health saw him forced to leave his castle and move into the city. In 1951 at the at of 88 he died, with Marion Davies by his side. Though he passed away, the company he began remains to this day one of the largest news conglomerates in America – and its president is the grandson who bears his name, William Randolph Hearst III. Not bad for an empire that began with a single failing San Francisco newspaper, a young man with an appetite for controversy, and a healthy infusion of parental cash.

Pictures via wikimedia except where stated.

[1] Ironically the Journal had been founded by Pulitzer’s brother Albert.

[2] Though he did also have to publish a retraction to part of his original story, as Clemencia was a bit appalled by some of his more lurid fabrications.

[3] Covered by the musical and film “Newsies”.

[4] The Democrats lost anyway, so it didn’t really matter.

[5] A strange mixture of an electoral group and an organised crime family that ruled the political scene in New York from the 1790s until the 1930s.

[6] The name came from one of his most popular magazines, which is still published today as Cosmo.

[7] Literally “novel with a key”. A 19th century practice designed to let people write fictionalised versions of real life events while avoiding lawsuits, by changing the names of all those involved. The “key” would thus be compiled by the reader to figure out exactly who each of the characters was in reality.