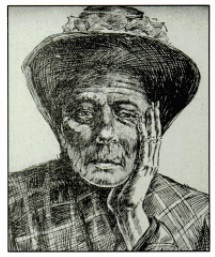

Mary Ellen Pleasant, Businesswoman and Civil Rights Activist

If you’ve heard of Mary Ellen Pleasant before, then chances are that what you’ve heard wasn’t good. “Mammy Pleasant” has often been a favourite of sensational accounts, the “evil Voodoo Queen of San Francisco” who made a good villain to scare the public with. But in reality, that isn’t what Mary Ellen Pleasant was. She was something far scarier to many in her time and since. Something that sent shivers down their spine. Something that drove them not just to try and destroy her, but to damn her memory and condemn her to a century of slander. She was that most terrifying of things in 19th century America, an assault on everything they considered not only normal but possible – a rich and successful black woman.

Where and when Mary was born isn’t very clear, not least because she herself often told contradictory stories about it. She celebrated her birthday on the 19th of August, and the the year must have been sometime between 1812 and 1817. Most sources go with 1814, and that might even be right. Her mother had been a black slave, and it’s almost certain that Mary herself was born into slavery. Her father is more of a mystery – he was probably white, though he might have been Native American or Hawaiian. The latter was one of the origins Mary herself claimed, along with a Philadelphia birthplace; though she also claimed to have been born in Virginia, being (like many female slaves) the result of her mother being raped by a white plantation owner. She also could have been born in Georgia. The one constant was that she always maintained her mother had been born in Louisiana and was a full-blooded black woman.

All of this confusion might have been deliberate on Mary’s part. She first definitely turned up in Nantucket as the servant of an old Quaker woman named Grandma Hussey. One of her memoirs tell a story of her being bought and freed by a couple named Williams before being sent on to the Husseys, and of her adopting the name of her rescuer’s wife, Ellen Williams, in gratitude. But like most Quakers, the Husseys were dedicated abolitionists and it’s entirely possible she was actually an escaped slave they were sheltering. That would definitely explain why she tried to muddy the waters about her origin. On the other hand, it may just be that Mary didn’t know where she came from, and the stories were just her way of trying to cope with this personal history that was lost forever.

Officially Mary was an indentured servant to the Husseys – a free person, with all the rights that entailed, [2] but bound to to work until her debt to them was paid off. In reality though, Mary was treated as one of the family. She was fair-skinned due to her mixed race and was able to pass for white. She did this for convenience’s sake, though she always hated doing so. Phoebe Hussey, the granddaughter of Mary’s mistress, was a girl about Mary’s age and the two became lifelong friends. When Phoebe married Captain Edward Gardner, Mary also became lifelong friends with him and with the whole Garner family. They were active in the abolitionist movement and also in the Underground Railroad, helping slaves escape the southern states. When Anne grew up, the Gardners helped her find a job in Boston as a tailor’s assistant, and that’s where she met James Smith.

Like Mary, James was mixed race, like her he could pass for white, and like her he hated it. His father had been a Cuban white man who had married a mixed race woman and had raised his son to hide his heritage, but to fight for it. James was a wealthy businessman with an import export business and a plantation near Harper’s Ferry, both of which he used as key components of his track on the Underground Railroad. Mary and James fell in love and got married, and she helped him move escaped slaves from Virginia to Nova Scotia, where the slave hunters couldn’t follow them. When he died suddenly some time between 1844 and 1848 he left her both of his businesses, the public one and the secret one.

James had always kept Mary at a distance from his work on the Underground Railroad, but now that she was running it she became much more hands on. There are stories of Mary disguising herself as a white male jockey in order to sneak onto plantations and guide the slaves to freedom. It was on one of these trips down south that she met her second husband John James Pleasant, a ship’s cook. JJ (as he preferred to be called) sometimes spelled his surname as “Pleasants” or “Pleasance”, leading to a rumour (that Mary quietly encouraged) that Mary’s new surname actually came from her “father”, a former governor of Virginia named James Pleasants. JJ was from New Orleans, like Mary’s mother, and like her he was of fully African descent. As a result he and Mary had to keep their marriage a secret while she was officially a “white woman”. No marriage certificate exists, but it’s generally thought that Mary’s friend Captain Edward Garner may have married the pair in his capacity as a ship’s captain.

There’s a persistent story that JJ was related to the Laveau family, and that he introduced Mary to the family’s famous matriarch Marie Laveau. Unsurprisingly Mary’s adventures during this time are fairly obscure, given the nature of her work. Whether or not she ever met the woman dubbed “the Voodoo Queen of New Orleans” isn’t known for sure, but it is actually quite likely as around this time Mary began practising that religion. [3] If she ever did, anyway – as with much of Mary’s life, this is buried in speculation and hearsay.

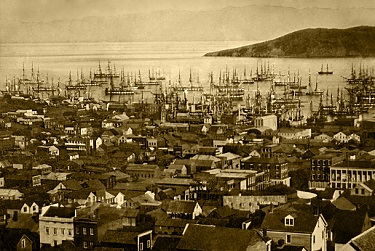

By 1851, all of Mary’s dangerous secrets were beginning to catch up with her. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 had given the slave hunters of the southern states legal license to act on northern soil and to compel the local authorities to assist them. This didn’t shut down the Railroad, but it did make life more difficult for its conductors. In order to throw the bloodhounds off her scent, Mary began considering moving from Boston to the West Coast. After a scouting expedition by JJ confirmed that California had potential. Slavery was officially banned in the state, but it remained practiced in many plantations where the law was defied. The benefit there though was that slaves who escaped were actually protected by the law, and the Fugitive Slave Act didn’t come into effect since the slaves didn’t cross a state line in the process. The place was also generally ignored by the slave hunters who concentrated on slaves fleeing north. So Mary Ellen Pleasant, under the guise of “Mrs Mary Ellen Smith”, moved to San Francisco in March of 1852.

Mary had sold her business interests in Boston, leaving her with a decent amount of capital which she invested in a series of restaurants and eateries around the city. She staffed these with free black workers (including some of her Railroad passengers), all of whom were aware of her secret activities and who were fiercely loyal. They kept her informed of the table gossip among her rich white clientele, while she herself rubbed shoulders with them at exclusive social events. Naturally the practical Mary was quick to monetise this valuable information, hiring a clerk named Thomas Bell to manage her investment business which soon became incredibly profitable. Within 20 years Mary would have a fortune of thirty million dollars (over half a billion in today’s money), making her one of the richest women in America at the time.

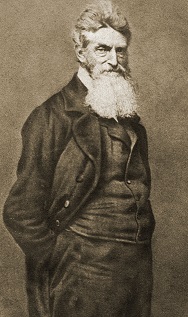

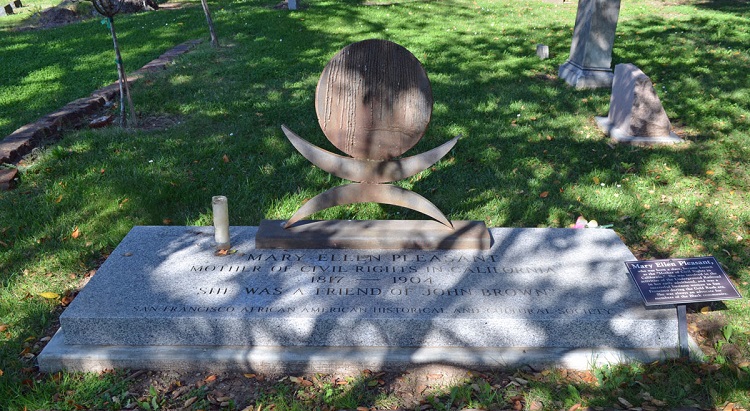

During her first fifteen years in San Francisco Mary maintained her cover of “white businesswoman”, but that didn’t mean she neglected her work on the Railroad. Instead she turned San Francisco into a surreptitious terminus, integrating escaped slaves into the local free black workforce. In 1857 she also became involved with John Brown’s plot to turn the cold war between abolitionists and slave holders hot. Details are difficult to pin down, but it seems that Mary traveled to Canada in 1858 and gave the abolitionist firebrand thirty thousand dollars in cash to support his efforts. When Brown was later captured and executed after his attempted raid on Harper’s Ferry (alongside Harriet Tubman, who escaped), a note in his pocket was found that was signed WEP. It’s been speculated that the note might have been smudged and misread, and the signature might actually have been MEP – Mary Ellen Pleasant. Regardless of how true that was, for the rest of her life Mary proudly described herself as a “friend of John Brown”.

Mary continued to build her empire over the next decade, expanding into laundries and boarding houses among other interests. San Francisco had been founded as a mining town, which meant that there were huge opportunities for businesses that provided labour considered “not manly”. These were not down-market establishments – one Governor of California even lived in one of Mary’s boarding houses. As a result of her influence within the white community, Mary quickly became the de facto leader of the black community in San Francisco, and got the nickname of “Black City Hall” for her ability to solve their problems. How the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861 affected Mary isn’t certain, but it did lend a new patriotic fervour to her abolitionist activities. She was a lobbyist for the law change in 1863 that allowed black people to testify in court, which they had previously been forbidden to do. And in 1865, after the north had won the war and slavery had finally been officially eradicated, Mary did something that she had been waiting forty years to do. When the census was sent out, Mary Ellen Pleasant filled in her ethnicity as “Black”.

As you can imagine, the revelation that one of the richest women in the state (if not the country) was black led to a huge amount of confusion and scandal. Most white Californians decided rather quickly that either it wasn’t true, or else that Mary had gained her fortune through crime and blackmail. The most obvious manifestation of this was how they seized on her other change, that of using her second husband’s surname. “Mrs Smith” had been a respected pillar of the San Francisco community, but “Mammy Pleasant” was a rank outsider. “Mammy” was a common nickname for an older female black slave, given in the patronising parody of affection that slaveowners deigned to show for their “property”. Naturally Mary hated it, and in fact it was said that any mail she received address to “Mammy Pleasant” was returned unopened.

As with most of the country, after the Civil War there was a backlash in California against black civil rights. During the war it had been patriotic in the North to avoid racism, but after the war efforts were redoubled to stop black people “getting uppity”. It was that sort of mentality that led to the war hero Harriet Tubman’s arm being broken by a railway conductor in New York, and it was the same sort of mentality that led California to refuse to ratify the constitutional amendments that gave black people civil rights or the right to vote. One of the justifications given for the latter was that it was “a slippery slope to giving Chinese immigrants the vote”, in a doubling down of the racist agenda.

Naturally Mary was at the forefront of the fight for black civil rights after the war, and in 1866 she won what may have been the first post-war victory in that battle. Ironically, it was on the same ground that battles would still be fought a century later – public transportation. When Mary and two other black women were thrown off a streetcar by a conductor who insisted it was “whites only”, he couldn’t have expected that she would have the resources to take him to court. But she did. Mary dropped her case after the company agreed to make it official policy to allow equal access to their streetcars, but two years later she took another company to court for the same thing. This time it went all the way to the California Supreme Court, where it was officially ruled that it was illegal for access to public transport in California to be restricted by race.

JJ Pleasant died in 1877, leaving Mary a widow once more. Whether he and Mary ever had any children is a source of speculation. If they did, they would have been born in secret during the time she was pretending to be a “white widow”. There are some stories that she had a daughter who she became estranged from, but this might have been one of her many god-children. As with most things in her life, the waters are too muddy to say for sure. And one of the major things muddying the waters came only a few years after JJ’s death, when Mary gained a great degree of unwelcome publicity from a very nasty divorce case involving a US Senator.

Senator William Sharon was in many respects a very typical 19th century US politician – a lawyer and businessman, somewhat on the sharp side (there were rumours around how he managed to get control of his business when his partner died), and fully part of the upper classes that Americans insist they don’t have. In a similar class was Sarah Althea Hill, the Missouri-born daughter of an attorney who had left her a reasonable inheritance. Sarah was one of the few upper-class white people in San Francisco who did not shun Mary Ellen Pleasant, and the two became friends. That friendship was to prove a double-edged sword in 1884 when Sarah Hill sued William Sharon for divorce on grounds of adultery.

William and Sarah had met in 1880, when she was 30 years old and he was 59. At that time, she claimed in court, he had married her but they had agreed to keep the marriage a secret in order to prevent scandal and conflict with his family. William and his legal team claimed that instead Sarah had agreed to become his mistress, with an allowance of $500 a month. When Sarah produced the marriage certificate (with Mary as a witness) it was denounced as a forgery. (Mary was also paying for her friend’s legal team.) Naturally, as inevitably happens, the case devolved into a trial of Sarah’s character. The prosecution’s main angle of attack was her friendship with Mary Ellen Pleasant – what sort of respectable white woman would be friends with a black woman, after all? And especially one who, they implied, was both an evil sorceress and a criminal of the most depraved sort. The defense tried to counter this with an equally racist stereotype, painting Mary as the type of sympathetic grandmotherly “black mammy” that a good upper-class woman would take her problems to. The fact that when Mary took the stand she met neither of these stereotypes was utterly irrelevant. The press in particular took great delight in turning her into a pantomime villain far removed from reality.

Sarah won her case in December of 1884, despite the overtly racist tactics of her opposition. The senator appealed, dragging the case on. The stress began to take its toll on Sarah and her behaviour started to become more erratic, something which may have unfairly influenced the later courts. The senator died in November of 1885, but his family kept up the appeal and in December (a year after the original decision) the judge ruled in his favour. The following astonishing passage from the court ruling is worth quoting:

…it must also be remembered that the plaintiff is a person of long standing and commanding position in this community, of large fortune and manifold business and social relations, and is therefore so far, and by all that these imply, specially bound to speak the truth… On the other hand, the defendant is a comparatively obscure and unimportant person, without property or position in the world…

Rarely has the right of the rich to trample on the poorer been so overtly expressed. Of course, that wasn’t the end of it. Sarah married David Terry, one of her lawyers, and the two continued to fight the case. Terry had a personal vendetta with one of the judges involved in the case, and the courtroom arguments occasionally descended into outright violence. Both of them were jailed for contempt, and David Terry was eventually shot and killed by a “bodyguard” hired by the judge, who then used his influence to have the man exonerated. Sarah was committed to an asylum in 1892, where she spent the last 45 years of her life, condemned by society for the crime of daring to stand up to power and privilege.

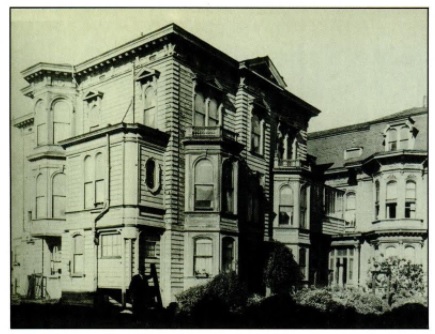

Mary was unable to come to her friend’s rescue in 1892, as she had problems of her own. She lived in a mansion she had designed herself, and allowed her business partner Thomas Bell and his family to live there. A popular fiction sprung up that she was his housekeeper, and like many of the contradictory assertions that allowed the people of the time to maintain their racist facade over reality this soon became an established “fact” in the popular consensus. When Thomas Bell died in a fall in 1892, his widow Teresa took advantage of this consensus to seize control of the mansion and of Mary’s fortune. Whether Teresa was driven by opportunism, or whether she actually was racist enough to be incapable of accepting Mary’s actual business relationship with her husband is irrelevant to the results. She was aided by the poor documentation around Mary’s finances, as she had been forced to use Thomas’ name in cases where a black woman’s name would not be accepted. The papers, of course, had a field day claiming (among other things) that Mary had used witchcraft to take control of Thomas, and that his death had been no accident but murder at her hand. So after a short court battle, the richest black woman in America was summarily divested of her fortune and thrown out of the house her money had paid for.

Fortunately for Mary, her friends in San Francisco were well aware of the untrustworthiness of the papers and stood by her as she had stood by them. The old lady spent the last twelve years of her life in relative comfort, and died in 1904 around the age of ninety years old not living in poverty (as the gloating newspapers claimed) but instead in comfort, surrounded by friends. One of those friends was a woman named Olive Sherwood, who had Mary buried in her family plot in Tulocay Cemetery. Her funeral was well attended, and ignored by the media. One newspaper’s obituary gloated “Mammy Pleasant Will Cast Spells No More”, though another writer commented that “if she’d been white, and a man, she’d have been president”.

Even now, a century after Mary Ellen’s death, the viciously racist spectre of “Mammy Pleasant” haunts her memory. Books and articles to this day repeat the slanders against her as fact, and the few examples of solid research refuting these are like voices in the wilderness. Still, the people she did so much for have never forgotten it. In 1965, a century after her battles in court, she was honoured by the Historical and Cultural Society of San Francisco as “the Mother of Civil Rights in California”. They gave her a grand marble tombstone, which in accordance with her own final wishes was engraved with the phrase “She was a friend of John Brown”. The tombstone was replaced in 2011 due to deterioration, in a ceremony honouring her memory. Meanwhile the trees she planted by the mansion she built and lost are now the city’s smallest public park, named in her memory. It’s something, but it’s hardly what a woman who did so much deserves. Perhaps one day Mary Ellen Pleasant will finally get the recognition she deserves.

Images via wikimedia except where stated.

[1] A gigantic caveat to this article. Mary Ellen Pleasant’s life has been the subject of a huge amount of misinformation, rumours stated as fact, and outright fabrication for over a century. As such while I have done my best to cut through the false information and obvious smears in order to get to the truth of the matter, it’s almost certain that some of the details in this article are going to be incorrect. (It’ll be in good company, as it seems that almost every article about her on the internet contains at least one major inaccuracy.) As such, please feel free to comment with any corrections you can substantiate. Thank you.

[2] Despite the assertions of the mealymouthed charlatans who peddle the “Irish slavery” myth, there was a million miles of difference between an indentured servant and a slave. No indentured servant could be torn away from their family to be sold to a faraway plantation, for example, or be beaten near death for the slightest infraction, or be raped by their owner with impunity and then forced to bear their children into slavery.

[3] The Voodoo religion in 19th century America was (and still is) a magnet for sensationalist tripe written by people who consider any non-Christian religion as equivalent to devil worship. As such it’s difficult to pin down the exact details around much of this part of Mary’s life. In fact some people think it’s all entirely a fabrication and she was actually Episcopalian.

[4] There are many pictures online that claim to be of Mary Ellen, but solid research has shown most are actually pictures of Queen Emma of Hawaii.