John Bodkin Adams, A Curious And Dubious Doctor

For the profession of doctor to work in society, people need to trust them. Most honour that trust but a few abuse it, some in horrific ways. One such scoundrel was John Bodkin Adams. Quite how deep his violation of that trust went is something that time and botched investigations have left us unable to know, but it’s certain that he was one of the greatest scoundrels to ever bear the title of General Practitioner.

John Bodkin Adams was born in Randalstown in Northern Ireland in 1899. His father Samuel was a watchmaker, and was also a preacher in the Christian Brethren, a Protestant group. He was named for his mother Ellen’s brother John Bodkin, who was well known in in Brethren circles for his successful missionary work in China. John had a younger brother named William, and there was also a young girl in the family. Her name was Sarah Henry and she was John’s cousin, who had been taken in by his mother after her own parents died. John was a student at a boarding school in Coleraine when his father died in 1914 of a stroke.

In 1916 John went to study medicine at Queen’s University Belfast, and it was while he was there that his family suffered another tragedy when his younger brother William died of the Spanish Flu. John also fell ill during his university years, possibly due to stress, and missed a year of studies. He graduated a year behind schedule in 1921 “without honours”, which is a nice way of saying that he barely passed; something which would match with the description of him by his lecturers as a “plodder”. Still, a pass was a pass and John was now a qualified doctor.

He had made few friends at university, being remembered as socially awkward, but he had a stroke of luck in his final year. In 1920 he attended a missionary conference held by the Brethren in Larne. One of the lectures was given by Arthur Rendle Short, a surgeon from Bristol. He and John spoke after the lecture about John’s famous uncle John Bodkin. When Arthur heard that John was a medical student he offered him a job in Bristol after he graduated, and John took him up on this after he graduated. However John lacked the acumen necessary for academic medicine, and after six months Arthur tactfully handed him an advertisement and suggested he look into it.

The ad was from a Christian weekly and was looking for a religiously-inclined man to join a group of GPs in Eastbourne, Sussex. So John applied for the position and was accepted. Eastbourne was a prosperous and pleasant town in 1922, and John soon brought his mother and cousin over to set up a household. Throughout his university career John had dealt with his lack of talent through solid hard work, and this now helped to get him a good reputation in town quickly. He made a lot of house calls, first on a bicycle (both his parents were avid cyclists) and then, as soon as he could afford it, on a motor scooter. John’s father had instilled in him a passion for cars and motors, and that scooter was the beginning of a lifelong delight in motor vehicles.

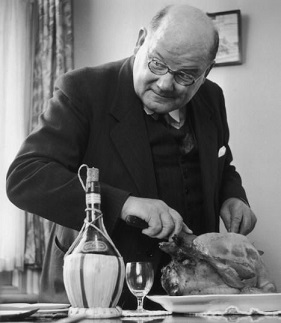

Sussex was home to many richer people, being in the country but close enough to London for visits. John’s reputation as a doctor willing to be called out at any hour soon helped him pick up some of these richer clients. Among his notable early clients were William and Edith Mawhood, who had a good deal of money from William’s successful Sheffield-based cutlery business. He was first called out to attend Edith after he broke her leg in accident but soon inveigled himself into the position of “family friend”, mostly through persistence. This not only got him into the local social scene but also allowed him to appropriate “gifts” from the household; including the time he admired William’s coat, asked him where he got it, then went and purchased an identical one – charging it to the Mawhoods.

Through the 1920s John’s social and financial status rose, and this was reflected in 1928 when he began employing a chauffeur to drive his two fancy cars. Cars themselves were his passion, it seemed, rather than driving them. Along with this John began to gain a slightly less savoury reputation, though few were willing to speak ill of him openly. In addition to presumptions like those he’d made on the Mawhoods, several patients found on a second opinion that he had scheduled them for unnecessary (and expensive) operations. And one woman whose eyesight was damaged in an accident (and thus would be unable to sign anything) was shocked to find that the doctor was doing his best to get control of her power of attorney. But the main thing was the wills. Part of his income came from bequests left in the wills of those he had attended in their final illnesses – a standard practice at the time, and the main reason why wealthy clients were so desirable. John took this to extremes though. The first warning sign of exactly how far he was prepared to go came in the form of Matilda Whitton.

Matilda was an elderly widow in her seventies when she moved to Eastbourne, and naturally the good doctor was often in attendance on her. He was good enough to loan her his car and chauffeur on occasion, and she became friendly with Sarah and Ellen. In gratitude she bought him a new car, a very extravagant gift but not necessarily alarming. More worrying was when she changed her will to disinherit her stepchildren and to leave the bulk of her estate to Doctor Adams. It was around this time that the staff at the hotel where she was living became concerned that the doctor might be overmedicating her, as she seemed to lose all energy while he was visiting her. A nurse who also attended her thought the doctor was behaving suspiciously. Matilda died in May of 1935, and John inherited her fortune. Her children challenged the will, but lost the court case. They might have been the ones responsible for John receiving threatening letters, warning him not to “bump off any more wealthy widows”.

The furore around Matila Whitton’s death might have saved Agnes Pike in 1939. She was another elderly patient, and her relatives became worried enough to bring in a second doctor – something which infuriated John. The second doctor could find no disease or medical reason for why she was being given the amount of morphia and barbiturates that John was giving her, and took over her treatment. After a couple of months without Doctor Adam’s care, she was almost fully recovered. It was probably incidents like this which led the local doctors to exclude him from their arrangements after war broke out, when they set up a pool to take over the patients of any doctors who were called up for active service.

John himself was never called up, but he did volunteer at the local hospital in order to make up the staffing shortages. He became a qualified anesthesiologist, though the hospital staff told stories of him not bothering to pay attention and making mistakes during operations. The most notable incident for John during the war though was his mother’s death in 1943, leaving him with only Sarah as family. John had never married, though he had briefly been engaged in the 1930s to a woman named Nora O’Hara. The engagement had been amicably broken off, and the local rumourmill had it that this was because Nora had discovered John was actually homosexual. Of course, with homosexuality illegal at the time it’s impossible to tell if there was any truth to this or if it was just a juicy bit of gossip.

After the war John continued receiving legacies, and his fortunes continued to grow. By some estimates he was the wealthiest GP in England, which to a certain type of person meant that he was obviously the best GP in England. One of the most high profile of his clients was Edward Cavendish, the Duke of Devonshire, who had been a minister in the wartime government. Harold was in attendance by the duke’s side in 1950 when he died of a heart attack, and signed the death certificate saying that he had died of natural causes. There were later some questions around this, as legally an inquest should have been held since the death had been a sudden one but John did not notify the coroner. John may not have wanted to get too much in the public eye at the time, as one of his “elderly patients” named Edith Morrell had died less than two weeks earlier. Despite being a beneficiary in her will, John had claimed that he had no financial interest in her death on the death certificate. If he had told the truth, then a post-mortem would have had to be carried out and he may well have not wanted that to happen. Now, he may not have wanted the coroner looking too closely into his recent conduct.

John’s sister Sarah died in 1952 of cancer, leaving him alone in his household. He wasn’t without friends though, and one of the closest was Roland Gwynne. Roland was a former Mayor of Eastbourne who had been a decorated veteran of World War I. He and John became close friends, and went on shooting holidays to Scotland and Ireland. This friendship further fueled rumours that John was homosexual, as Roland certainly was (and was in fact being blackmailed by his butler over it). Through Roland John received even more high profile clients, and he soon became considered one of the top GPs in the country. The frequent deaths of his elderly patients and the sizable bequests he continued to rack up were all conveniently glossed over. And then in 1956 his patient Bobbie Hullett died, and things began to unravel.

Bobbie’s real name was Gertrude, but ever since she was a young girl everyone had called her Bobbie. She’d lived near Eastbourne since the 1920s, but it was only in 1950 that she became one of Doctor Adams’ patients. That was the year her husband Vaughan died of a heart attack, and Bobbie became sick through grief. John prescribed sleeping pills, which didn’t really help, and a holiday in Switzerland, which did. The doctor also introduced her to a friend of his named Jack Hullet, a widower who had been his patient for years. Jack and Bobbie struck up a friendship that blossomed into a relationship, and they married in 1952. Sadly in 1955 Jack went to visit Doctor Adams with stomach pains, and the doctor realised his friend had bowel cancer. He sent for a surgeon from London to perform the operation (as he knew it would be risky) which was successful in removing the tumour but which put a lot of stress on Jack. He was very ill for three months, during which time Bobbie became more and more stressed. Finally in March Jack suffered two heart attacks and died. John was in attendance, though he failed to give him the sort of treatment that would be expected for a heart attack. In fact he listed the official cause of death as “cerebral hemorrhage”, which was almost certainly not true but which saved embarrassment. He also, of course, lied on the cremation form and said he did not expect to benefit from Jack’s will.

Bobbie did not take her second husband’s death well, and went into a serious decline. John had prescibed her a heavy dose of barbiturates, which affected her strongly, and many of her friends began to suspect he was supplementing this with injections of morphine. Her maid even wanted to go to the police about this, though the other staff wouldn’t go along with it. Her friends became deeply worried when Bobbie started talking of suicide, and this was how John justified the sedation he had her on. Around this time she changed her will to leave him her Rolls-Royce, and she also gave him a cheque for a thousand pounds “as a gift”. A few days later Bobbie went into a coma. As John was away, another doctor was called, and when John returned he and this doctor disagreed as to the cause. John insisted that it was a cerebral lesion rather than a barbiturates overdose, against much of the evidence. When Bobbie died, an inquest (something John had always managed to avoid) was inevitable.

The inquest gave a conduit for the rumours which had been swirling around the doctor, and the press soon began to show an interest. They discovered the 1935 case over Matilda Whitton’s will, and as a result they soon descended on Eastbourne in force. An army of journalists went over the town and dug out every story they could find about Doctor John Bodkin Adams. And there was a lot to find out. They soon discovered that the good doctor was the beneficiary of not just dozens but hundreds of wills over the years. Rumours soon began to spread that “the deaths of several other local women are being investigated”, and though no paper directly accused John it was clear between the lines where they felt the guilt lay.

The media focus soon led the local police to call in Scotland Yard to take over before the inquest began. The dynamite revelation was that of the pathologist, who confirmed that Bobbie had indeed died of a barbiturates overdose. He also specifically called out Doctor Adams for not having suspected an overdose at once when he was the one who had prescribed the drugs for her. The evidence also looked poor for John when his treatment of Bobbie was reviewed, but the judge in his summing up concluded that though the doctor had clearly been negligent he had not crossed the line into criminal negligence. As such he told the jury that the decision they had to make was between accidental overdose and suicide, and they chose suicide.

John was vocal in his relief after the verdict, but now that Scotland Yard had begun looking into him they had no intention of stopping. They soon hit an unexpected snag, however, when they found that the British Medical Association had sent a letter to all the GPs in Eastbourne reminding them that “doctor-patient confidentiality extends to the patients of other doctors” – a clear signal to not say anything about Doctor Adams. However they soon began to build up an array of cases going back as far as 1935, almost entirely consisting of wealthy widows who had rewritten their wills to favour Doctor Adams after they had come into his care, and who had died soon after. Eventually they settled onto the case of Edith Morrell in 1950 as the one with the most suggestive evidence, as the doctor had given her large doses of morphine despite her not being in pain and had recorded her cause of death as his old favourite, cerebral hemorrhage. In addition he had lied on her cremation form and had in fact benefitted substantially by her death.

In October of 1956 two Scotland Yard men called on Doctor Adams. They asked him about the drugs he had on the premises, and one caught him trying to hide two bottles of morphine in his pockets. When asked about Edith Morrell’s death, the doctor said:

Easing the passing of a dying person isn’t all that wicked. She wanted to die. That can’t be murder. It is impossible to accuse a doctor.

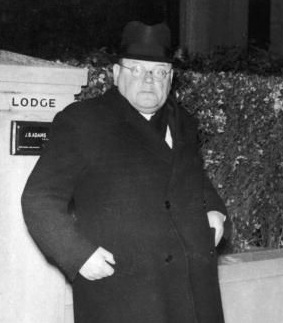

That, combined with lies that Doctor Adams told about the amount of morphine and barbiturates he purchased (which turned out to be immense) were enough to prompt the higher ups at Scotland Yard to order an arrest. This was protested by some among the investigation, as they felt that some of the other cases might be surer if they were allowed to investigate further. Edith had been cremated, after all, but some others could be exhumed. They were overruled, as after all the doctor could always be charged on these other cases later. So on the 19th of December 1956 John Bodkin Adams was arrested for the murder of Edith Morrell.

In the eyes of many in the media, the doctor was already guilty. Yet from the start the handling of the case was peculiar. For example a copy of the inspector in charge of the case’s report, effectively the entire case for the prosecution, was handed over to the BMA who almost certainly passed it on to the defence team. Similarly the notebooks written by the nurses in the case of Edith Morrell were entered into police evidence but though the defence somehow received a copy of them the prosecution did not know this. By producing them at into evidence while cross-examining one of the nurses, the defence managed to throw these key witnesses off balance and place doubt n their evidence. So despite the fact that the notebooks did actually confirm that Edith was receiving unusually high levels of morphine and other drugs, the defence managed to turn them to their advantage.

The trial then turned on the motive for the murder, and the defence were able to make headway here by pointing out that the amount John received under Edith’s will was paltry, especially compared to his own wealth. This was one of the reasons why the police would have preferred a different case by prosecuted, and why they had wanted to bring in some other deaths to provide evidence of “system” on John’s part. However the attorney-general had overruled them on both counts, and had instead left the death of Bobbie Hullett on the docket for a later trial. The expert witnesses that the prosecution had depended on both gave their opinion that Doctor Adam’s course of treatment had been designed to be fatal, but both were undermined by the defence, based on their examination of the nurse’s notebooks (and possibly the report received from the BMA). When the judge summed up the case in favour of the defence, it wasn’t surprising that the jury went along with him and acquitted John Bodkin Adams of murder.

What was surprising was when the Attorney-General decided to use a legal tool called “nolle prosequi” to drop the second charge without it going to trial. This was highly unusual, but it left John a free man. He did suffer some consequences, though. Based on the evidence uncovered in the investigation he was charged with forging prescriptions and lying on cremation forms, which led to him being fined £2,400 and struck off the Medical Register. This would only stick for five years though, as after that he applied to be reinstated and was able to resume private practice.

There was a great deal of suspicion at the time that there had been a finger on the scales of justice, and that either the prosecutor, the judge, or both had been influenced to direct the trial. The most prosaic theory was that Roland Gwynne had used his influence to have the second charge dropped, as he had been seen dining with the Lord Chief Justice during the trial. More wild were the theories that the government had put pressure on the judge. The Duke of Devonshire, the patient whose death Doctor Adams had attended after Edith’s, had been the brother in law of Harold MacMillan who had become prime minister only a few weeks before the trial. It was alleged that the new PM was eager to avoid any scandal that might impact him from digging into the the Duke’s death. Another theory had it that the government did not want to cross the BMA, as at the time their commitment to the newly formed NHS was shaky at best. Given the huge public popularity of the NHS at the time, any government that brought it down would fall soon after. None of these conspiracies really hold much water though – the trial records make it clear that the prosecution did want to win, while the judge’s bias (if any existed) could be explained by the fact that both he and the Attorney-General were competing to take over as Lord Chief Justice when the current one retired.

After the trial John gave an exclusive interview to Percy Hoskin Adams laying out his side of the story. Adams was the only reporter who had gone against the media tide before the trial and called out the persecution of John as unjustified, and John appreciated that. He sued a couple of the newspapers who had gone a bit too far in vilifying him and won, and that led the others to back off and the whole thing to die down. Once he was allowed to practice again he even got back more than a few of his previous clients, though Scotland Yard continued to keep an eye on him. But John led a quiet life until 1983, when he fell while shooting and broke his leg. He died from complications of the injury three days later. Of course, now that he could no longer sue for libel several newspapers printed sensational headlines bringing back the allegations of mass murder and trumpeting the fact that the doctor left an estate of over £400,000 behind him. A large number of journalists turned up at his funeral, where they were berated by the preacher for their “vicious whispering campaign of rumour and vilification”. Then John was (somewhat ironically) cremated, and his ashes were taken back to Coleraine and buried alongside his parents.

Nowadays it is almost impossible to evaluate Doctor John Bodkin Adams without the shadow of Doctor Harold Shipman falling across the discussion. The revelation in 2000 that a GP was Britain’s most prolific serial killer naturally (if not rationally) made the allegations against John seem more believable. In 2003 the police records on the trial were unsealed, and the historian Pamela Cullen used them to argue in her book about the case that John was acquitted less because of the evidence and more because the police at the time didn’t really understand the motivations of serial killers. Based on John’s behaviour and writing several modern psychologists have agreed that he was most likely a sociopath, and it seems most likely that his primary purpose in overmedicating his patients was not to kill them but to make them dependent on him. It was notable that whenever one of his patients resisted his “kindness” John would react with extreme anger, and he had a similar response to being denied the “respect” he felt his position deserved. He may not have intended to kill his patients, but he was certainly not averse to avoiding any fuss when they died. The historian Jane Robins also points out [1] that 42% of the deaths he recorded had as cause of death “cerebral hemorrhage” – a statistical impossibility. The evidence seems overwhelming that at the very least John Bodkin Adams was guilty of manslaughter, and at worst that the jovial doctor, so convinced of his own self-worth, somehow managed to get away with murder.

Images via wikimedia and Murderpedia except where stated.

[1] In her excellent book on the Adams case, The Curious Habits of Doctor Adams.