Caroline Norton, Criminal Conversationalist

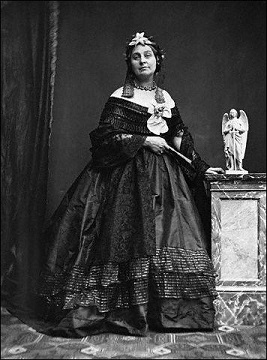

It’s a testament to Caroline Norton’s charm and personality that despite her involvement in a sex scandal that nearly brought down a British government in the notoriously prudish 19th century, she managed to remain free of public distaste. It might have helped that, unlike Gertrude Campbell, she was the one with aristocratic connections that her husband lacked. It helped, of course, that she had a genius for knowing exactly how far she could get away with pushing her case without outraging morality. But perhaps most of all it was that her tragic life and the injustice she faced cut through the prudishness of Victorian England, leaving people uncomfortably aware of their own contradictory morality.

She was born as Caroline Sheridan in 1808. Her family were genteel, though not aristocratic. Her father Thomas was from a political family, while her mother (who was also named Caroline) was the niece of the Earl of Antrim. Caroline was the second of three sisters, as well as four brothers (though one brother died in his childhood). Thomas dabbled in soldiering and politics, and helped his father Richard run the Drury Lane Theatre in Dublin (which he owned) and it was while he was in the city that Caroline was born. Some time afterwards he contracted tuberculosis, for which there was no cure at the time. A hot dry climate was considered to help reduce the symptoms, so his father used some influence to get Thomas a job in the colonial administration in South Africa. His wife and Caroline’s eldest sister Helen went there with him in 1813. The climate clearly didn’t have enough of an impact though, as Thomas died in 1817.

Thomas’ death left his family severely impoverished. Caroline Sheridan now had no income and seven children to raise, the oldest only eleven years old. She was left dependent on the kindness of relatives and the income from her dead husband’s share in the Drury Lane Theatre, which was meager enough. Still, she got by. It helped that the family lived rent-free in a “grace-and-favor” apartment, one owned by the crown. Richard Sheridan was the one who arranged this for his grandchildren, through a friendship he had with the Duke of York. It probably helped that Caroline Sheridan the elder was well liked. Most people remembered her as both quiet and pretty, with an absolute horror of causing trouble. Indeed her husband had once said that “her extreme quietness and tranquillity is a defect in her character”. It’s not surprising, then, that she found her daughter Caroline a trial.

I have tasted each varied pleasure,

And drunk of the cup of delight;

I have danced to the gayest measure

In the halls of dazzling light.

I have dwelt in a blaze of splendour,

And stood in the courts of kings;

I have snatched at each toy that could render

More rapid the flight of Time’s wings.

But vainly I’ve sought for joy or peace,

In that life of light and shade;

And I turn with a sigh to my own dear home-

The home where my childhood played!

– My Childhood’s Home, by Caroline Norton

All three of the Sheridan girls were considered notable beauties, and they were nicknamed “the three Graces” after the minor Greek deities so beloved of sculptors and painters. Helen was the eldest, older than Caroline by a year and probably the closest to her mother. Georgiana was the youngest, younger by a year. Georgiana was considered the prettiest, but Caroline was always the cleverest. That wasn’t seen as an advantage for a young girl then, though, and she reportedly drove her mother to distraction. She and Helen were close, and used to collaborate on on musical projects as children – Helen wrote the music, and Caroline the lyrics. Then Caroline was sent away to a boarding school in Surrey, which was where the trouble began.

The problem came when the girls at the boarding school went to visit the estate of the local landowner, William Norton (who was a baron). William’s brother George, who was a twenty-three year old barrister, saw the fifteen year old Caroline among the group of girls and decided he wanted to marry her. (That probably tells you something about his character right away.) He told the governess of the school who gave him Caroline’s mother’s address, and he sent her a letter. Caroline Sheridan was non-committal, as George was only a penniless barrister after all, but he was his brother’s heir and so possibly a reasonable prospect. So she wrote back to tell him that he would have to wait until Caroline was eighteen, hoping that she might make a better match before then.

There was every chance she might. In 1824 Helen was married to Price Blackwood, the young heir to the barony of Dufferin and Claneboye. His family opposed the match, due to the poverty of the Sheridans, but young Price wouldn’t be gainsaid. Caroline was introduced to high society and made many friends, but her sharp wit and intelligence seems to have scared off any potential suitors. Once she turned eighteen her mother began pressuring her to take up George Norton’s offer of marriage before she became an old maid. Against her better judgment Caroline agreed to marry him. It would turn out to be a huge mistake. Caroline’s natural forthrightness and tendency to speak her mind were almost guaranteed to enrage a husband who was both far less intelligent than she and deeply resentful of anyone who could defeat him in a debate.

Caroline soon learned that when her husband found himself unable to solve a problem with words he was swift to turn to violence. In their first argument after their honeymoon he threw an ink-stand and some books at her head. Two months later he struck her for the first time. It would not be the last. Initially the arguments came from his insistence that since she had brought no dowry to the marriage she owed him complete obedience but soon the tables turned. George was the Tory MP for Guildford when they married but he proved so incompetent in the role that he was deselected in the next election, while Caroline had become a celebrated society hostess who was friends with all of London’s literary set. George, of course, found it impossible to follow his wife’s conversation at her parties and often took out his sense of inferiority on her when they were alone. He drank, and he beat her. On one notable occasion he “indulged in bitter and coarse remarks respecting a young relative” of hers who (scandal of scandals) continued to dance even though she was married. When Caroline defended her relative George grabbed her by the back of the neck and threw her at the floor, causing so much noise that Price Blackwood (who, along with Helen, was staying with them at the time) broke open the door to protect her. One can only imagine what George had to say (and worse) once the Blackwoods went home.

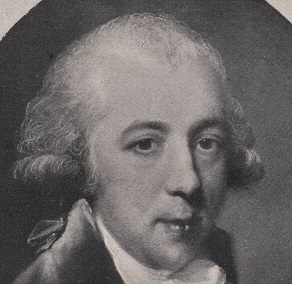

In 1829 Caroline released her first book, The Sorrows Of Rosalie, and gave birth to her first son, Fletcher. She might have hoped that this fulfillment of her wifely duties would lead to a softening of George’s attitude, but if so she’d have been mistaken. It was around this time that George lost his seat as an MP, and had to rely on Caroline’s connections with the government (who were Whig, to add insult to injury) in order to get him a new job. She met with the home secretary William Lamb (aka Lord Melbourne) [1] and persuaded him to give George a job as a magistrate in the police courts. Rather than be grateful, George soon became convinced that Caroline and William were a bit closer than he liked – a conviction that would fester over the years to come. He also didn’t like Caroline becoming the editor of two periodicals – La Belle Assemblée and Court Magazine. But he needed her contacts, so he tolerated her activities.

After publishing a great deal of poetry in 1830, Caroline devoted herself to motherhood for a few years. Fletcher was followed by Thomas in 1831 and William in 1833. While Caroline was seven months pregnant with William she was beaten and knocked down the stairs by George, and the servants were forced to intervene to save her. It was a miracle she didn’t lose the baby. Three years later, that miracle was not repeated. While Caroline was pregnant with their fourth child George beat her so viciously that she miscarried. This might have been prompted by the book she had just published, which was called The Wife, and the Woman’s Reward. It was about a woman with an unfaithful husband, and a woman who was beaten by her brutish brother, both of which George might have felt slighted by. Or it might just have been some chance remark from her that gave him an excuse to vent his rage on his favourite punching bag. Either way, it was the final straw. Caroline took her children and fled the house.

Modern readers may ask themselves why Caroline had not left her husband far earlier, or why those who knew he was beating her did nothing to intervene. They should understand, in England in the 19th century wives had no rights. This was brought home to Caroline in two calculated moves by George after she left him. First, he stole her children. Fletcher, Brinsley and William were all snatched up and sent to his relatives in Scotland and Yorkshire. Caroline had no legal recourse. In fact, the law was entirely on George’s side. Only the father of children had any rights to them under the law at that time. Caroline didn’t even have the right to visit her children, and it would be many long years before she saw any of them again. Then George struck again, reminding her that once a woman married she ceased to exist in the eyes of the law as a separate entity. Caroline’s sole source of income was the royalties from her books, but George sued and won to receive these royalties. A wife had no legal right to property or earnings – all money she earned belonged to her husband. Caroline was left with nothing.

Divorce wasn’t an option. Though technically it was possible, a divorce required an Act of Parliament. Obviously this was only available to the richest and most privileged in society who could commandeer the legal apparatus of the realm to sort out their problems. Plus it was only available to men, of course. Caroline did find one way to strike back, though. As her earnings were George’s, so were here debts. So she just had all her bills sent to him to pay. This might be what prompted him to overreach himself. Caroline had remained good friends with Lord Melbourne, and rumours had been floating around for a while that they were having an affair. [2] George threatened to take the Lord to court if he wasn’t paid off. Lord Melbourne was Prime Minister by now, and a scandal like this could mean the end of his government. But he refused to be blackmailed. George was stubborn and vindictive enough to follow through on his threats, and in late 1836 he sued Lord Melbourne for “criminal conversation” with his wife.

“Criminal conversation” was a typically Victorian method of suing someone for adultery without having to mention sex, though everyone involved knew what it actually entailed. George, in typical fashion, was far more interested in hurting his wife than in actually winning the case. He took out newspaper advertisements detailing her “crimes” and taunting her with having sold off all her prized possessions, and then he tantalised her with promises of allowing her to visit her children if she would side with him in the trial. This wasn’t the first time he’d made such promises though, and he never fulfilled them. So Caroline remained resolute, and after nine days the jury in the trial threw the case out. The government remained standing, though Caroline and Lord Melbourne had to end their friendship and never spoke again.

Unsurprisingly, following her exoneration Caroline became a prominent figure in the fight to reform the laws around the rights of wives. She had already gotten involved in political campaigning after her seperation, writing a poem in support of factory workers’ rights. But this time she was fighting a battle she had a personal stake in. In 1837 she wrote and published Separation of Mother and Child by the Laws of Custody of Infants Considered, a searing indictment of the current state of the law. She pointed out the horror of the law and illustrated it by example – a husband who had broken down his separated wife’s door and torn away a child who was nursing at her breast, a woman who been forced to hand her children over to her husband’s mistress while he was in jail, and other such stories. (All backed up with documentation in the appendix – Caroline was no slouch.) She pointed out that though wives were thinking, breathing, intelligent people, in the eyes of the law they were as much their husband’s property as a brood-mare or a stretch of land he might purchase. She ended with an appeal to the lawmakers, that “for the peace of society, and the credit of humanity”, they should admit the mother’s right to her children to be considered.

Caroline and her fellow campaigners were rewarded in 1839 with the Custody of Infants Act. This wasn’t the first time a bill of this sort had been proposed, but it was the first time it passed. Under the act, though men were still automatically granted custody women were allowed to appeal to the courts for custody if the child was under seven and for access if it was older. It wasn’t much, all things considered. And it did still place justice out of the hands of anyone too poor to afford a solicitor to take the case to court. But it was a beginning – a recognition that women did have rights not just to their children but indeed that they had rights at all as individuals within a marriage.

My heart is like a withered nut–

It once was comely to the view;

But since misfortune’s blast hath cut,

It hath a dark and mournful hue.

The freshness of its verdant youth

Nought to that fruit can now restore;

And my poor heart, I feel in truth,

Nor sun, nor smile shall light it more!

– My heart is like a withered nut, by Caroline Norton.

Caroline’s victory didn’t see her children restored to her, though. The Norton family had estates in Scotland, which had (and still has) an entirely separate legal system. The new act didn’t apply there, so that was where George sent the three boys. And it was there that William, the youngest at nine years old, fell from a horse. His injuries were minor, but this was the pre-antibiotic age when even the smallest cut could prove fatal. He contracted blood poisoning and soon became seriously ill. When George realised the boy was dying he sent for Caroline, but by the time she reached Scotland her son was dead. She hadn’t seen him since he was only three years old.

After William’s death George (whether out of guilt or due to pressure from his family) agreed to let Caroline have custody of the other two boys and set up a trust fund to support them. This was not without conditions, the chief of which that she was not allowed to have any relationship with another man, and that George could reclaim them any time he wished. For the next few years Caroline lived in fear that he might decide to take her boys away from her. In 1847 she published Aunt Carry’s Ballads for Children. Officially this was written for the children of her brother Richard and her sister Helen, for unsurprisingly she was a doting aunt to their sons and daughters. But it’s pretty clear that her thoughts were on her own children at the time, and the years of their youth that she had lost.

In 1848 George found himself in financial difficulties, and made a deal with Caroline where he gave her a deed of separation and a £600 a year support payment in exchange for access to the trust fund he had set up to support the boys. Later that year Lord Melbourne died. On his deathbed he swore that he had not had a relationship with Caroline, but he also expressed his regret that the court case had destroyed their friendship. In his will he left her an annual income of £480. Once George found out about this he stopped paying her the support he had promised, so Caroline once again started referring her creditors to him. (Since both of her sons were now adults, she no longer had to fear George reclaiming them in revenge.) This all culminated in a court case where George maintained that his original payment was conditional on Caroline receiving no other payments. This was in contradiction to the agreement he had signed with Caroline, but the court still ruled in his favour. Their reasoning? Caroline was a married woman, and as such she had no legal right to make contracts with anyone. Only her husband had that right.

Unsurprisingly, then, Caroline continued to campaign for social justice for women in abusive relationships. In fact, in 1849 she was painted into a fresco in the House of Lords as “Justice”. Over the next few years, she campaigned for divorce law reform. This culminated in 1855 when she gave testimony in Parliament. She pointed out that under the law as it stood a woman who left her husband could be forced to return to him both by the courts and by force if he so wished. A woman could be divorced by her husband for infidelity, but even if he was openly unfaithful she had no legal recourse. And most demeaning of all, if her husband did sue for divorce she wasn’t allowed to defend herself, but instead the case was considered to be her aggrieved husband suing her alleged lover for an affront to his property. The woman in the case wasn’t allowed to have an attorney and wasn’t even considered to exist as a person affected by the case.

The eventual result of this was the Matrimonial Causes Act in 1857. As with the Custody of Infants Act this was far from a perfect piece of legislation, but it was better than what came before. Divorce no longer required an Act of Parliament, but was now something that could be granted by the civil courts. Women could now sue for divorce, though the bar for them to be granted it was still higher than that for men. (On the other hand, a woman’s suit for divorce that included adultery did not have to name her husband’s lover while a man’s suit did.) The bill was very controversial, mostly due to the power it took away from the church, and William Gladstone (the future Prime Minister) made an attempt to filibuster it in Parliament. However the appetite for the bill among the general public was demonstrated by the fact that once the new court was established it heard three hundred petitions for divorce in the first year alone.

After the passage of the Matrimonial Causes Act Caroline largely retired from public campaigning. Thirteen years later she would celebrate the Married Women’s Property Act changing the law that had allowed George to steal the profits from her books, but that was a victory won by the next generation of female warriors. Similarly Caroline didn’t associate herself with the new generation of suffragettes fighting for the vote for women. She’d always claimed that she “didn’t believe in equality for women”, though whether that was true or whether it was just canny politics on her part is impossible to say. Regardless, Caroline passed on the torch and retired from the field.

Caroline’s retirement from public life was in part due to both of her sons having moved to the Continent, possibly to get away from their father. Thomas met a woman named Maria in Naples and married her in 1854. The pair gave Caroline her only grandchild in 1855. Fletcher died of tuberculosis in 1859, which may also have been part of what drove Caroline out of public life as she was devastated by the loss. She continued to write though, producing several novels and collections of poems throughout the 1860s to great acclaim. Ironically she was hailed by some as a “female Byron” – ironic as her former friend, Lord Melbourne, had separated from his wife in 1825 after she had a very public and messy affair with Byron. [3]

How mournful seems, in broken dreams,

The memory of the day,

When icy Death has sealed the breath

Of some dear form of clay.

When pale, unmoved, the face we loved,

The face we thought so fair,

And the hand lies cold, whose fervent hold

Once charmed away despair.”

– Not Lost, but Gone Before by Caroline Norton

In 1875 George died and Caroline was finally freed from her hateful marriage. George was still his brother’s heir to the barony that had led to his marriage to Caroline in the first place, so now the claim passed to Caroline’s son Thomas who inherited the title in 1877. The same year Caroline and a long-term friend of hers, the Scottish author William Stirling-Maxwell were married. Their wedded bliss didn’t last long though – news reached Caroline that Thomas had passed away, and the news sent her into a decline. On June 15th 1877 she died. She had fought for the recognition of woman’s rights under English law and won. It was the first such victory in a war that would continue for many years to come – a war that some may feel has not yet been won. Let us not forget it all began with a battered and abused woman who refused to accept that she could not have justice under the law.

Images via wikimedia except where stated.

[1] He wasn’t the Lord of Melbourne in Australia; in fact it was named after him.

[2] They might have been – Lord Melbourne was a notorious womaniser with a penchant for sadistic roleplay. The lightest rumours have him engaging in spanking sessions with bored aristocratic wives, while darker stories have him indulging his fetishes on young servant girls, a power dynamic that would have clearly compromised any consent involved..

[3] In one of those odd coincidences her name was also Caroline – Lady Caroline Lamb.