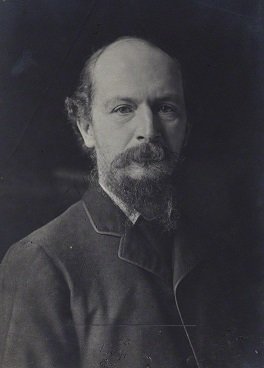

Algernon Swinburne, Dissolute Poet

Algernon Charles Swinburne was born in a suburb of London in April 1837, a few months before Victoria took the throne. One of his grandfathers was an earl, and another was a baronet, his father was a Captain in the Royal Navy who would become an Admiral before he retired. His family had a holiday home on the Isle of Wight and that was where he spent most of his childhood. He attended Eton, one of England’s most prestigious boarding schools. Swinburne was a natural rebel, and the canings given out for such behaviour at Eton led to his first realization that he took a sexual pleasure from pain. From Eton he went on to Oxford, the standard educational journey of an aristocratic male of the 19th century. Less standard was his almost being thrown out of Oxford for his outspoken support of the Carbonari, Italian revolutionaries who tried (and failed) to assassinate the French emperor Napoleon III in 1858 and who killed eight bystanders with their bomb. He was “rusticated”, an Oxford term meaning temporarily expelled. Though he was allowed back to the university in 1860, he left the same year without getting a degree.

It was while he was at Oxford that Swinburne made a great many of the friends who would be his peers over the next few decades. Most notable was the painter and poet Dante Gabriel Rosetti. Dante was not a student at Oxford (he was around thirty at the time), but was at the university to paint a series of Arthurian murals on the walls of the Oxford Union along with Edward Burne-Jones, another painter who also became one of Swinburne’s dearest friends. Swinburne’s grandfather, Sir John Swinburne, lived in Northumberland and Swinburne spent most of the summers of his university career with his grandfather – partially due to a love of Northumberland and the north of England in general, and partially due to the artistic retreat at the nearby house of Lady Pauline Trevalyan. She was a friend of the art critic John Ruskin and a patron of Dante’s. At Wallington Hall (her large country mansion), Swinburne met Dante’s sister the poet Christina Rosetti, the poets Elizabeth Barret Browning and Robert Browning, and the painter John Everett Millais. Millais and Dante had been among the founders of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, who had revolutionised art a century before. Wallington Hall was where Swinburne entered into the English artistic scene.

I that have roses in my name, and make

All flowers glad to set their color by;

I that have held a land between twin lips

And turn’d large England to a little kiss;

God thinks not of me as contemptible.

– Rosamond

It did take Swinburne a while to make his own mark on that scene, however. His first work was a pair of plays, though as reviews of them at the time pointed out they were closer to poems in a play style, lacking enough action to put on the stage. Both were historical plays done in the style of a medieval court romance. The first was The Queen Mother, a play about Catherine de Medici and the St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre. [1] The second was Rosamond, based on the life of Rosamund Clifford the mistress of Henry II. Popular myth (as opposed to boring facts) had it that Rosamund was kept within a labyrinth by the king, but this did not save her from being murdered by Eleanor of Aquitane, Henry’s jealous queen. Both plays were reasonably well received, and do show Swinburne’s promise and potential. However they were a little too niche to gain much popular acclaim, and a bit too tame to excite much controversy. In 1865 Swinburne released Atalanta in Calydon, a work which aimed to bring the mood and setting of Greek tragedy into modern English. It was a huge critical success, and his first collection of poems was eagerly awaited. It’s fair to say that nobody expected what they got.

For no man under the sky lives twice, outliving his day.

And grief is a grievous thing, and a man hath enough of his tears:

Why should he labour, and bring fresh grief to blacken his years?

Thou hast conquered, O pale Galilean; the world has grown grey from thy breath;

We have drunken of things Lethean, and fed on the fullness of death.

– Hymn to Proserpine

At the time Poems and Ballads was released, Swinburne was sharing a house with Dante Rosetti. Dante’s wife had died in 1862 and he had abandoned their family home and moved into a house on Cheyne Walk in Chelsea. Swinburne was also grief-stricken, as Elizabeth Siddal (Dante’s deceased wife) had been one of his best friends. Despite this bond, Swinburne was not exactly the ideal housemate. He was primarily (though possibly not exclusively) homosexual, and combined this with his masochistic tendencies to riotous effect. Swinburne wasn’t really a masochist. Rather he had algolagnia – a neurological condition where the brain interprets pain signals abnormally, which results in them causing overwhelming sexual arousal. The most commonly told story is that Dante once had to leave the studio where he was working in order to ask Swinburne to keep the noise down, and found him and a boyfriend sliding naked down the bannister. Swinburne had always been an excitable type (as well as suffering from fits, possibly due to epilepsy). He played up to his reputation and enjoyed exaggerating tales of his depravity. It was Swinburne himself who invented the most scandalous rumour about him. Dante kept a menagerie of animals in the house, and Swinburne spread the tale that one of them had been a chimpanzee which Swinburne had first had sex with, and then killed and ate.

She slays, and her hands are not bloody;

She moves as a moon in the wane,

White-robed, and thy raiment is ruddy,

Our Lady of Pain.

– Dolores

Poems and Ballads lived up to this “Algernonian exaggeration”, as one biographer puts it. The book included vehement atheism, sado-masochism, cannibalism and lesbianism. In fact Swinburne may have been the first to use “lesbian” in its modern meaning, in the poem Sapphics. The book was a huge success, but the controversial content led to a charge of indecency being placed against the book. As a result Swinburne’s publisher sold the rights to John Camden Hotten. Hotten was a bookshop owner and publisher who made a habit of publishing risque materials, including the wonderfully titled Lady Bumtickler’s Revels. He gave free reign to Swinburne, though most of his more controversial works (such as La Souer de la Reine, a tale about a twin sister of Queen Victoria who becomes a prostitute) were kept to a strictly private circulation.

His more public works included what some consider his best creation – a trilogy of plays covering the life of Mary, Queen of Scots. The first, Chastelard, tells the story of a French page who travelled to Scotland in her escort, became infatuated with her and who was eventually executed for having concealed himself in her bedroom. He also wrote an elegy for Baudelaire, where he mourned the death of a kindred spirit.

Thou sawest, in thine old singing season, brother,

Secrets and sorrows unbeheld of us:

Fierce loves, and lovely leaf-buds poisonous,

Bare to thy subtler eye, but for none other

Blowing by night in some unbreathed-in clime;

The hidden harvest of luxurious time,

Sin without shape, and pleasure without speech;

And where strange dreams in a tumultuous sleep

Make the shut eyes of stricken spirits weep;

And with each face thou sawest the shadow on each,

Seeing as men sow men reap.

– Ave Atque Vale

Over the next fifteen years Swinburne became a notorious figure on the London literary scene, legendarily debauched and a bad influence over all around him. One story has it that Dante persuaded a female friend of his sister’s, the American actor and writer Adah Menken, to give Swinburne his first heterosexual experience. Adah went along but had to abandon the experiment, complaining to Dante “I can’t make him understand that biting’s no good!” He drank like a fish, usually to the point of his health nearly failing. Then he’d go to Northumbria where he dried out and recovered his strength, before plunging back into the capital again.

It was for this, that men should make

Thy name a fetter on men’s necks,

Poor men’s made poorer for thy sake,

And women’s withered out of sex?

It was for this, that slaves should be,

Thy word was passed to set men free?

– Before A Crucifix

Though Swinburne was most notorious for his controversial works, they weren’t the only thing he produced. He wrote literary criticism, initially taking up the role after his complaints about the criticism his own work received led him to decide to give it a go himself and turning out to be extremely good at it. He also wrote political poems – he continued his support for Italian nationalism with A Song of Italy, while his poem Before A Crucifix is a scathing indictment of organised religion that ironically betrays a deeply religious side to his personality.

Swinburne’s lifestyle put a great deal of strain on his health, which was never strong, and as he passed his fortieth birthday many of his friends began to fear for his safety. One of those friends was Theodore Watts-Dunton, a poetry critic. Theodore had also been a friend of Dante Rosetti, who had suffered a breakdown in 1872, and had gone into a decline that he never recovered from in 1874 (he died in 1882 as a complete recluse). Theodore was worried that Swinburne would suffer a similar fate, and so he decided to take extreme measures. In 1879 he made Swinburne move into his house in Putney, where he kept him as a houseguest and virtual prisoner for the next thirty years. Swinburne was cut off from most of his bohemian friends, many of whom denounced Theodore for his interference. He had, they insisted, “saved the man but killed the poet”. That’s a compelling narrative, and one put by influential people. As such a lot of people take it as truth – but as the facts show, it was far from the case. Swinburne still had a lot of writing to do. In 1881 he finished the last of his trilogy of plays about Mary Queen of Scots with Mary Stuart, where her story reached the inevitable tragic conclusion he had just himself avoided.

About the middle music of the spring

Came from the castled shore of Ireland’s king

A fair ship stoutly sailing, eastward bound

And south by Wales and all its wonders round

To the loud rocks and ringing reaches home

That take the wild wrath of the Cornish foam.

In 1882 Swinburne released what he considered to be the greatest thing he ever wrote, Tristram of Lyonesse. The epic poem was to Arthurian myth what Atalanta in Calydon had been to Greek – a transfiguration of the story of the doomed lovers Tristram and Iseult into modern verse and sensibility. Sadly it was not as well received at the time as it deserved. The critic Edmund Gosse wrote a scathing review where he described it as “pages upon pages of amorous hyperbolic conversation”, and the perception (tied into the false narrative of Swinburne’s artistic decline) stuck. It wasn’t until the following century that the poem started to receive the attention it deserved.

Swinburne also continued his scholarly works, writing books on Victor Hugo and Ben Jonson among others. Both he and Theodore also wrote entries for the Encyclopedia Britannica. It was perhaps the staid respectability of this type of work that most incensed his former friends. Confirming his “establishment” credentials, he was nominated for the Nobel Prize in literature six times during the 1900s. In 1909, thirty years after Theodore forcibly took him into care, he died at the age of 72. He was publicly mourned as one of the great English poets, something that would have been unthinkable back in his hellraiser days. But the underground society too had their own memorial. Many of the works he had written for his friends privately, works such as The Cannibal Catechism and The Ballade of Villon and Fat Madge, which had been deemed too scandalous for publication, were now privately printed and surreptitiously distributed. It was a fitting way to remember the other side of Charles Algernon Swinburne – the side some might call terrible, but which was still a part of what made him a great poet.

Images via wikimedia except where stated.

[1] The same subject as one of the plays of Christopher Marlowe.