Barbie, Lenin and Fake Hand Grenades | My Childhood in the Wild East

I was born in a country that today doesn’t exist anymore. It was called the German Democratic Republic (GDR), or East Germany. Founded in 1949, after the Second World War, as a socialist bulwark against West Germany, it became a satellite state of the USSR. The GDR officially ceased to exist in 1990, following the reunification of West and East Germany which had been ushered in by the peaceful revolution of 1989.

What was it like growing up under a socialist system?

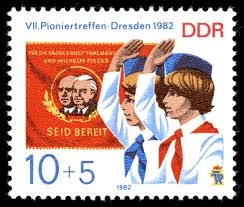

My memories are of a happy carefree childhood which didn’t differ much from other childhoods. Except of course everyday life in the GDR was highly politicised and the influence of the ruling socialist party (SED) also reached into the private sphere. For a child that meant being part of political youth organisations from the age of six. You started out as a so called young pioneer (Jungpionier), then moved on to be a Thälmann pioneer, to eventually become a member of the FDJ (Freie Deutsche Jugend – Free German Youth).

Source

The pioneers would wear their uniform, a white shirt, a blue and a red scarf, on occasions such as the first school assembly of the year or commemoration ceremonies for the victims of fascism. As pioneers we pledged to abide by certain rules, coincidentally ten commandments… While for the young pioneers these mainly consisted of general rules such as study hard, respect your parents and be kind to others, the rules got more overtly political for the Thälmann pioneers. By the age of nine, when you joined the Thälmann pioneers, you pledged, for example, to strengthen socialism and help the forces of peace in the world by studying hard and doing good deeds. As well as that, you vowed to fight against the propaganda and lies of the imperialists.

Now, I’m not really sure what exactly I did to fight imperialist propaganda at the tender age of nine. I think my activities in that area were mainly limited to doing posters for the school praising comrade Lenin. Dear uncle Lenin who, as we were always reminded, had stressed the importance of education – ‘Learn, learn and learn’. Political indoctrination in school largely went over my head. I didn’t really care what the congress of the communist party of the USSR had decided and found the endless meetings we had to attend to discuss those things very boring.

While the image of Lenin as a great political leader figured highly in East German political education, it was mainly Ernst Thälmann whose example GDR children were supposed to follow. To study, work and fight like Thälmann was our motto. Thälmann, or Teddy as he was known to GDR children, was the leader of the German communist party during the Weimar Republic who was killed by the Nazis in 1944.

To reinforce the idea of defending the cause of socialism, as Thälmann had done to the ultimate sacrifice, the education of young children often had underlying militant connotations. Besides my largely positive childhood memories of the GDR, this aspect stirs up the occasional disturbing image.

[perfectpullquote align=”right” cite=”” link=”” color=”#2FB3C9″ class=”” size=”16″]”A fun day out with your class mates, for example, was accompanied by shooting air rifles at targets and eating dinner from a mobile field kitchen.”[/perfectpullquote]As Thälmannpioniere we had pledged to protect peace and to hate all war mongers. In order to do that, militaristic components were introduced in after school activities in a seemingly playful way. A fun day out with your class mates, for example, was accompanied by shooting air rifles at targets and eating dinner from a mobile field kitchen (Gulaschkanone in German). While I didn’t mind most of these thing, I didn’t much care for playing around with guns, especially when you were not given the choice of opting out of it.

I also have vague memories of throwing around fake hand grenades during sport lessons, which probably explains my life long struggle with exercise. It’s clearly a symptom of post-traumatic stress disorder rather than plain old laziness. The sight of fifteen and sixteen year old students running around the school yard in full camouflage gear wearing gas masks is also one lingering in my memory.

A less traumatic childhood activity was taking part in the well organised recycling programme of the GDR. Glass, paper and other recyclable materials were collected and dropped off at collections points which paid a small amount of money in return for those materials. Schools organised large recycling collections to raise money to support the struggle of emerging socialist states such as Mozambique, Angola and Nicaragua. As Thälmann pioneers we had pledged to show solidarity with all people fighting for their freedom and national independence. A friend of mine remembered years later that he resented the children of Nicaragua for getting the toys his mother made him donate. Solidarity with your socialist brethren has its limits when you’re ten years old.

In general the recycling runs were a fun thing to do, at least that’s how I remember them. We’d roam around the neighbourhood going from door to door asking if people had any recyclables to give us. There was always a great sense of achievement when you managed to get on top of the collection leader board kept by the school. Of course, the biggest excitement was discovering glossy West German magazines amongst your collected paper. Those would be poured over endlessly and studied in great detail, giving us a glimpse into the life ‘over there’ as West Germany was often referred to.

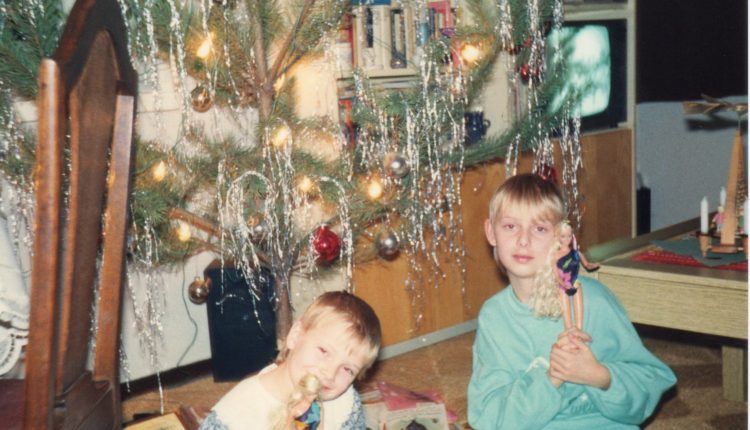

Outside of the school collections you were able to earn some additional pocket money by returning recyclables. Although it was nice to have some extra cash, there was nothing really exciting in the shops to spend it on. Specialty shops, the so called Intershops, which sold a variety of Western luxury items not available in regular GDR stores, did exist but only accepted hard currency. If you were lucky enough to have relatives in West Germany who would give you the odd Mark, you were able to enter the temple of capitalist consumerism. There you would marvel at the shiny trinkets the imperialist oppressor had managed to produce, no doubt under the extraction of the workers’ blood, sweat and tears. I remember agonising over the decision what to spend my couple of Marks on and eventually settled on a pencil case which was filled with chewing gum. The height of luxury, however, was reached when I received a Barbie doll at Christmas 1988.

Despite our strenuous efforts to protect socialism by recycling like champions and studying as hard as Lenin had told us to, the GDR came to an abrupt end with the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989. At the night of the 9th November (I was eleven years old by then) I was watching events unfold on TV not really understanding what was going on and thinking the world had gone mad. The following day I went to school where the teacher assured us everything would carry on as normal and there was no need to panic. Some students though were already missing and wouldn’t be returning to class.

What followed was a year of confusion, chaos, excitement, possibility and uncertainty. 1990 – the year zero. Suddenly I had to go to a new school since the school system of the GDR was replaced with the West German one. In the GDR children were educated in one school from the age of six up to sixteen. The West German system consisted of a primary school and three different types of secondary school you attended from the age of 12. This was all very confusing to me, I just wanted to go to the same school as my friends.

[perfectpullquote align=”right” cite=”” link=”” color=”#2FB3C9″ class=”” size=”16″]”Entering this new glamorous world, I quickly forgot about comrade Thälmann’s struggle and just focussed on how many Barbie accessories I could buy.” [/perfectpullquote]

As a child I was mainly focussed on the day to day practicalities of my little life and looked to my parents for guidance as the world as we had known it was quickly being dismantled. But the adults often didn’t have answers either. My sister recalled how she was writing our address in her new school bag shortly after 1989. She wrote down street, city and then paused to turn to my dad asking him what she should put for country. The GDR was gone but we weren’t part of West Germany either, what country where we living in? My dad told her to just leave it blank for now.

A new currency also arrived, the West German Mark. In addition, each GDR citizen received one hundred Mark of welcome money, a payment which had been granted by the West German state since 1970 for East Germans arriving in West Germany. In 1990, however, claiming welcome money reached unprecedented heights as thousands of East Germans were queuing eagerly at banks to receive the payment.

After my family and I had collected our welcome money, we headed straight to the KaDeWe, which then was probably one of the most expensive luxury department stores in West Berlin. Aim high I say! Entering this new glamorous world, I quickly forgot about comrade Thälmann’s struggle and just focussed on how many Barbie accessories I could buy.

It certainly took some time to adjust to our new life and it wasn’t without its set-backs, especially for my parents who lost their jobs after 1990 and had to retrain for new careers. We muddled through, though, and came out successfully at the other end. Today I try to remember this strange country I used to call home and attempt to reconcile my memories with those of others who, unlike me, experienced the GDR as an oppressive dictatorship. Oscillating between nostalgia and condemnation, our collective memories help to shape the picture of what life was like in the Wild East.