Joseph Vacher, the “French Ripper”

Joseph Vacher, possibly the most infamous French serial killer, was born in 1869 to a poor farming family in an Alpine valley in southwest France. He was the youngest of fifteen children, and little is known of his early life. What is known is hard to separate from tales told later when his true monstrosity was revealed to the world, and accounts often vary wildly over the details of his life before he achieved infamy. He was educated at a Catholic school, and he had a notoriously poor temper combined with a high opinion of himself. At the age of 17 he joined the army – perhaps through conscription, or perhaps voluntarily to try to get himself a better life.

His poor temper was a detriment to his military discipline, and promotion was at first slow in coming. Depressed by the lack of recognition, Vacher made an attempt at suicide – slashing his own throat with a razor, though not deeply enough to kill himself. Some accounts have it that this led to his dismissal from the military, but most say that this actually impressed his superiors enough to win him the promotion he sought, making him Corporal Vacher. While on leave, he met a girl named Louise Barant and fell in love with her. The feeling was not mutual. In 1893, after his military service had ended, he tracked her down and proposed marriage to her. When she refused, mocking the idea that she might have said yes, he pulled out a pistol and shot her four times before turning the gun on himself. Luckily, Louise survived – unluckily, so did Vacher. One bullet buried itself in his skull where it could not be removed, damaging him such that the right side of his face was partially paralysed, and his right eye was constantly infected. What effect the damage to his brain had is hard to gauge.

Vacher’s actions led to him being hospitalised, and then transferred to a mental institution in the town of Dole. Here he was held for a year, before being released as “cured”. He became a migrant day laborer – one of the 400,000 homeless poor who wandered around the country living from hand to mouth on whatever work they could find or food they could beg. Lost among this mass, even despite his unique appearance (with the scar on his neck and the paralysis of his face), Vacher would prove impossible to track down once he began to kill.

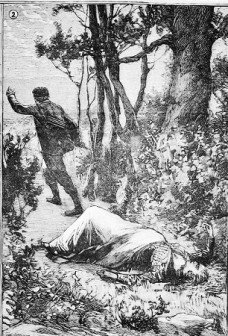

His first victim was Eugénie Delhomme, a 21-year old millworker whose body was found mutilated in a hedge by a passing shepherdess. She had been strangled and stabbed in the neck, with the frenzied assault continuing even after she was dead. This first murder seems to have been impulsive, perhaps promoted by a refusal of his advances, but once Vacher had killed he instantly developed a taste for it. His later attacks were more deliberately planned out. Rather than town-dwellers, he began hunting the adolescents who would range out into the wilderness as shepherds. He stalked and killed at least ten of these teenagers, both male and female, subjecting them to sexual assault and post-mortem mutilation. The true count of his victims may be higher, and the police soon began to draw connections between the tales of the scarred vagrant seen in the vicinity of these killings. But among the throng of 400,000 displaced labourers, it was like looking for a needle in the haystack.

Vacher was eventually captured, but it was his own carelessness rather than police acumen that led to his arrest. In 1897 he attacked a woman in a field in Ardeche, in the south of France, but the older woman was more capable than his usual prey and was able to fight him off while calling for help. Her family (either her brother and father, or husband and son, depending on the account) came running to her aid and soon overpowered and subdued Vacher. He was held in a local tavern while the police were called, and reportedly entertained the locals by playing the accordion while they waited. The police arrested him on charges of assault. While they may have recognised him as fitting the description of the “Killer of little shepherds”, they had no evidence to link him to it – until Vacher, without any prompting, suddenly began to confess to his crimes, blaming them on “moments of frenzy”.

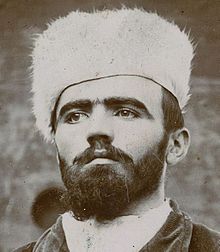

Vacher became a media sensation, and this inflated his ego dramatically. His scarred face, wearing a distinctive white rabbit-fur hat, became a mainstay in the papers. His original defense was that his blood had been “tainted”, either through the bite of a rabid dog when he was a child or through the quack cure he was given for the bite, but Vacher soon decided that his original explanation for his madness was too prosaic, and began to declare himself sent by God, like Joan of Arc. Despite his self-proclaimed divine mandate, he was still a deadly dangerous man. When the warden of his prison was foolish enough to be in a room alone with him, Vacher nearly beat him to death with a chair. Only the guards drawn by the warden’s screams saved his life.

The key question that arose was simple: was Vacher insane? In a legal sense, could he be considered responsible for his actions? The premier medico-forensic expert in France, Alexandre Lacassagne, was retained to determine the answer to this fact. Lacassagne was one of the founding fathers of modern criminology, and his French school of criminal psychology stood as a rival to Cesare Lombroso’s Italian school. In many ways Lacassagne’s was the more progressive of the two – Lombroso insisted that criminal behaviour was solely a function of biology, while Lacassagne insisted that environment and inclination worked hand in hand. [1] It was with this attitude that he set out to examine Vacher.

Over the course of five months Lacassagne and his associates examined Vacher. The principal of “legal insanity” was not well-established in French law at the time, though the broad definition they took was analogous to the M’Naghten Rules determined in Britain fifty years earlier. [2] First, they determined that he was aware of what his crimes were at the time he committed them, which was apparent from his behaviour in attacking the woman in Ardeche and the prison warden. Next, they determined that he was aware that the crimes were wrong, through his attempts to hide what he had done. In one case, after leaving the site of one of his murders, he had been stopped by a gendarme on a bicycle. When the gendarme saw from his papers that the two had served in the same regiment, he told him of his hunt for a murderer, and Vacher lied to him about seeing a man running across the fields. In the end, while the panel determined that Vacher was occasionally delusional and suffered from a persecution complex, they decided that this was not the root cause of his actions. As such, he was declared fit to stand trial.

In October 1898 Vacher entered the courtroom in Bourg-en-Bresse. Though he was considered responsible for eleven murders he was charged with only one, since that would be sufficient to have him executed. As he entered, he shouted “Glory to Jesus! Long live Joan of Arc! Glory to the great martyr of our time! Glory to the great saviour!” Some speculate that Vacher’s theatrical play for insanity was due to a belief that he could escape from any asylum. He definitely sought to turn the trial into a farce, wearing his white rabbit hat as a “symbol of purity”, and screeching and howling during the reading of evidence. But Lacassagne’s thorough case to prove Vacher sane was more than enough to convince the jury. Vacher was found guilty, and sentenced to death.

On the 31st December 1898, Vacher was taken to the guillotine. He was far from resigned to his fate, and fought against his jailers as he was dragged to the scaffold. This was the last execution carried out by Louis Deibler, a 75-year old man who had become the chief executioner of France nine years earlier. The decapitations had taken their toll, and he was about to retire on the grounds of having developed a phobia for the sight of blood. Still, he held on to his post long enough to see an end put to Vacher. As he was prepared for the blade, Vacher declared “You think to expiate the faults of France by having me die? That will not be enough. You are committing another crime. I am the great victim, fin de siecle.” These were his last words, and a few moments later the “Killer of Little Shepherds” was no more.

Images via Wikimedia and Radio Boston.

[1] Unfortunately Lacassagne was also a firm believer in the quack science of phrenology, the belief that the shape of one’s skull shapes one’s personality. This greatly harmed his standing in the scientific community.

[2] Named after Daniel M’Naghten, who had murdered the Prime Minister’s secretary in 1843. The House of Lords commissioned a panel of judges to determine the rules to be applied at his trial as to whether he could be acquitted on grounds of insanity. He was, and the rules became the basis for the legal defense of insanity around a large part of the world.