John Lynch, the Berrima Axe Murderer

Berrima in New South Wales was never a large town. Today its population is around six hundred people, and in the nineteenth century it was half that. One morning in February 1842 the citizens of Berrima made the discovery that it was now one less than it had been before. The body of Kearns Landregan, a farm labourer, was found dead with his skull split open. Suspicion immediately fell on a man named John Dunleavy – a short man with an Irish accent. He was the last person who had been seen with the dead man, he had been driving a cart that matched tracks found at the scene of the crime, and when he was arrested there were bloodstains on his shirt and he was wearing Landregan’s hat. Dunleavey was a newcomer to the area – he had purchased a farm the year before from the Mulligan family, who had left down to avoid being investigated for illegally selling grog. Or so people had thought. As they looked back on it, they realised that nobody had actually spoken to the Mulligans before they left town. Dunleavy was arrested, and was soon recognised as being a former convict labourer named John Lynch, who had worked on a nearby ranch and who had been involved in a murder case six years earlier. Lynch maintained his innocence, but the discovery of Landregan’s belt at the Mulligan farm was enough to see him sent to trial. Soon evidence began to appear linking him to other murders, and eventually the entire story of John Lynch began to come to light. It was a story that would chill the nation.

John Lynch was born in County Cavan in 1813, but nothing is known of his life between then and his conviction for the crime of “false pretences”. It is not true, as some of the more excitable accounts have it, that he had “murdered his father” – that would have resulted in a death sentence, while Lynch was sentenced to be transported to Australia. In accordance with his sentence he was taken to the colony of New South Wales on the a convict ship (possibly the Dunvegan Castle in 1832, possibly the Asia in 1831 or the Java in 1833). Like most such convicts he was bound to a seven year period of servitude, after which he would be free to travel about Australia as a settler, or to return home if he wished (and could afford it). For this period of service Lynch was assigned as a farm labourer.

Lynch next resurfaced in August 1836 as a murder suspect. As a convict labourer he had been moved around farms assigned to assist as needed, and in 1836 he was labouring on a farm named Oldbury in Argyle. Oldbury had been founded by James Atkinson, a noted agricultural scientist who did much to improve the state of farming in Australia. He died in 1834, and his widow Charlotte (author of the first children’s book in Australia [1]) remarried in March 1836 to a man named George Barton who she had hired as overseer of the farm. Under Australian law at the time this gave Barton total control of the farm, which proved to be as much of a disaster as his marriage to Charlotte. Barton was a violent alcoholic who would eventually be convicted of manslaughter in 1854, and he was hated by every worker on the farm. A few months after his marriage, Barton was held up on the road by a masked gang who robbed him of everything he was carrying before tying him to a fence post and flogging him, leaving him there to be found by the next passer by. (Some stories have it that Charlotte was accompanying him and that the gang raped her, but if so this was left out of the newspaper reports.) A man named Watt was captured and executed for the crime, but rumours around Oldbury had it that Lynch had been one of the masked gang members and that it was his grudge against Barton that had prompted the flogging. When Thomas Smith, another labourer on the farm, was arrested for stealing a saddle and then released without charge the general opinion was that he had given some information on Barton’s flogging. And when Thomas Smith turned up beaten to death, Lynch was an immediate suspect. The prime witness was a man called Michael Hoy who said that Lynch and the other suspect, a man named John Williamson, had persuaded Smith to accompany them out of the labourers’ hut and returned later covered in blood, and said that Smith had been “put where he could say no more”, and that he was a man who “could not have gone to Sydney without hanging people”. There was some supporting evidence to Hoy’s statements, but Lynch defended himself and seems to have destroyed Hoy under cross-examination. He threw enough doubt on Hoy (including claiming that he was the one who actually had the motive to kill Smith) to thoroughly muddy the waters, and a sympathetic summing up by the judge sufficed to see Lynch found “not guilty”. As later events showed, this was a mistake.

John Lynch was granted his Certificate of Freedom in 1841, and became master of his own destiny. His actions from there on are covered by his later confession, but it was soon expanded on, distorted and altered beyond recognition by the various newspaper accounts. Still, the overall timeline seems to fit the accounts at the the time. According to it Lynch began his career as a free man by stealing eight bullocks from a farm where he had been a labourer. He tried to sell them to a fence he knew named John Mulligan, but Mulligan didn’t offer him what he thought was a fair price. So he set off to Sydney to sell them. On the road he met a man named Edmund Ireland and a young Aboriginal boy [2] who were taking a wagon-load of produce from Bungendore to Sydney, a trip of 170 miles. They decided to travel together for safety’s sake, though one could hardly be less safe than in the company of John Lynch. At some point on the road he murdered the air of them with a hatchet, hid the bodies, set his eight bullocks loose and took the wagon on himself. Just outside of Sydney around the 7th of August Lynch had the bad fortune to run into Thomas Cowper, the man who had hired Edmund Ireland to drive the wagon in the first place. (He was travelling as part of a convoy at the time, and Cowper said that there were two men on the wagon.) Thinking on his feet, Lynch claimed that Ireland had been injured on the road, and that he had hired Lynch to complete the journey for him while the Aboriginal boy helped him get home. Cowper was convinced, and said that he would meet them at Parramatta in Sydney. Of course, Lynch never turned up. Cowper advertised for information and tracked down a horse’s bridle and the bacon from the produce. There the trail went cold, as Lynch had been smart enough to hire a local man to sell it for him.

Lynch’s second victims were a father and and son named Frazer who he met shortly after he got rid of Cowper’s produce and set off back south with his cart. The Frazers had left Sydney on the 8th August transporting a cargo belonging to Samuel Bawtree about 200 miles south. They met Lynch on the road and he arranged to travel with them, and was in their company on the 14th August when they checked in with Bawtree before setting out through the wilderness. It was the last time they were ever seen alive. According to some accounts of his confession, Lynch deliberately set the bullocks that were pulling his cart free and then persuaded the Frazers to loan him part of their team of horses to pull his cart. He then killed the son at a resting camp and persuaded the father that he had gone off in search of the bullocks, then killed the father. However it happened it is certain that Lynch killed the two men and concealed their bodies, which were not found until after he was caught. Bawtree placed advertisements seeking information, which led to several discoveries. The first was Cowper’s cart, which Lynch had concealed in the bush (after a few close calls with policemen who had been searching for it) while he went on with Bawtree’s cart. The second was the link between the thefts from Cowper and Bawtree, which also led to the conclusion that the Frazers, Edmund Ireland and the unnamed Aboriginal child had all been murdered. The third was a description of Lynch himself, though it left them really no closer to catching him. Whether through accident or design Snelling, the false name he had used on the trail, turned out to belong to another man who matched his description and it was he who the police sought. Eventually three other men (the unfortunate Snelling, and two men named Bailey and Brown who had travelled in convoy with Lynch into Sydney) were arrested for the murders and theft. Lynch himself got away, for the moment, scot free.

Lynch’s next step was to try to unload his ill-gotten gains. The incident with Cowper had been a very close call, and had put him off Sydney for the time being. So he headed back to John Mulligan to see if he would give him a better deal this time. Mulligan lived on an isolated ranch with his wife Bridget and the two children of her first marriage, John and Mary Macnamara. John Macnamara was around sixteen years old, according to later court records, and Mary was fourteen. As Mulligan and Lynch talked, something in the conversation drove Lynch to make a decision. Perhaps he was offered a bad price once again, or perhaps Mulligan mentioned his plan to sell the farm and move on to avoid suspicion. Whatever it was, it gave Lynch a truly diabolical idea. According to his confession, he offered to help young Johnny cut some firewood, then killed him in the woods and hid his body. He told the parents that Johnny had seen some stray horses and had gone to investigate, but when the young man didn’t return his mother went out to search. Lynch followed on the pretext of helping her, but when she found Johnny’s body he murdered her as well. He returned to the house and sneaked in, then ran up behind Mulligan and killed him with the same axe he had used for his other murders. The only remaining family member was young Bridget Macnamara, who had retreated to the kitchen and armed herself with a knife. Lynch easily disarmed the fourteen year old girl, then raped and murdered her.

Lynch burned the bodies of the Mulligan family, then contacted the owner of the farm saying that Mulligan had sold him (under the name of “John Dunleavy”) the lease for £700. The owner accepted this, and the locals (who may have been aware of Mulligan’s plans) also accepted this, though some suspicions were aroused when he was seen using some of the Mulligans’ equipment that they would have been expected to take with them. Still, he managed to keep the masquerade up for four or five months until February 1842. What he did during this time is unknown, though reports of Cowper and Bawtree’s wagons being seen together at a camping site in November suggest that he may have returned to strip Cowper’s cart of anything valuable or incriminating. It was found by a search soon after, but the trail remained cold. It was not until Lynch killed again that the law was back on his scent.

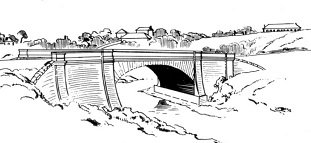

By February 1842 Lynch was settled in on the Mulligan ranch. He had hired a couple named Terence and Clara Bennet to run the farm for him while he was away, but he decided he needed another farmhand to help him bring the produce to market. On his way back from Sydney he met a man name Terence Landregan in the small town of Picton. Landregan had just finished a job, and he and Lynch hit it off. However at some point on the trip back to Berrima Lynch changed his mind. One theory are that Landregan mentioned he had some outstanding debts, which Lynch worried would bring attention to the farm. Another theory is that Landregan made mention of having the pay for his last job with him – he had £40 in cash when he left Picton, which was not on his body when it was found. Whatever the reason, Lynch decided that Landregan was of better use to him dead than alive. As the pair made camp by the Ironstone Bridge near Berrima he clubbed the other man to death, then concealed the body. He kept the £40, along with the dead man’s hat and belt.

The body was discovered on the morning of the 21st February by a labourer named Henry Sturges, who noticed cut branches piled up and moved them aside to find the body. He immediately contacted the local police, who investigated the site and found the tracks of a cart – notable, as one wheel had seized up and left a distinctive mark. The body was taken to the local morgue, and a call was put out for anyone who could identify it. A man named John Chalker, who kept a public house on the trail and who saw most travellers in the district, went to identify it. He recognised Landregan, and was able to tell the police that the dead man had actually stopped in at his public house for a meal, along with “John Dunleavy”. He and Landregan had been friendly and the two had discussed Landregan’s new job. As a result of this, Noah Chapman (Chief Constable of Berrima), Sergeant Freer and John Chalker went to the old Mulligan farm to arrest “Dunleavy”. They found him repairing a roof, and immediately restrained him. The constable noticed a bloodstain on the shirt he was wearing. “Dunleavy” explained it away as the result of an insect bite. The sergeant noticed a cart, and examining it found that its track width matched that of the cart that had been at the murder scene. It even had the stuck wheel from the tracks. The clincher was a hat they found in the bedroom of the house. Chalker was able to identify it, by a tear in the band, as the one that Landregan had been wearing when he stopped at the public house.

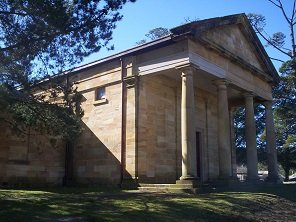

Lynch’s run of bad luck continued when he was put into jail in Berrima. A search of the Mulligan farm turned up not only a belt (which Landregan’s brother was able to identify as his) but also some of the property listed as stolen by Cowper and Bawtree. Meanwhile Chief Constable Chapman brought his predecessor, James Harper, in to view “Dunleavy”. Harper recognised him from the trial in 1835, and so his true identity as John Lynch was revealed. The press dubbed him the “Berrima Axe Murderer”, after the tomahawk he had used to kill several of his victims. By the end of March he was put on trial for the murder of Thomas Landregan, and though he tried to sell some of his possessions to pay for a defence lawyer this was blocked by the court on the grounds that his legal right to them was undetermined until after his trial. Still he maintained his innocence and defended himself in court. He did his best to cast doubt on the witnesses testimony, and to claim that the belt had been planted in his house by Landregan’s brother. The hat he claimed as his own, though when he tried it on in court it proved to be too large for him. His story was that the dead man had left him on the road claiming to have mislaid his money on the route, and had set off back to where he had lost it agreeing to follow and meet him at the farm. He also claimed to have bought the farm from the Mulligans with a legacy that had been sent on to him from Ireland. Despite what onlookers described as a credible performance from Lynch, and despite the fair summing up from the judge, on the 22nd March 1842 the jury found John Lynch guilty of murder.

Lynch was sentenced the following day on the 23rd, and the judge’s sentencing speech was a classic example of its kind:

John Lynch, the trade in blood which has so long marked your career is at last terminated, not by any sense of remorse or the sating of any appetite for slaughter on your part, but by the energy of a few zealous spirits… It is now credibly believed, if not actually ascertained, that no less than nine other individuals have fallen by your murderous hands. How many more have been violently ushered into another world remains unrecorded, save in the dark page of your own memory. By your own confession it is admitted that as late as 1835 justice was invoked on your head for a frightful murder, committed in this immediate neighbourhood. Your unlucky escape on that occasion, has, it would seem, whetted your tigrine relish for human gore, but at length you have fallen into toils from which you can not escape… The wily cunning, the artful devices, the blustering impudence which have so long sustained you in the pursuit of a lawless life, can no longer serve your turn.. The sentence of the law is, that you be taken hence to the place from whence you came, when you are to be taken to such place, on such day, as his excellency the Governor shall appoint, and be hanged by the neck till you are dead, and may the Lord have mercy on your soul.

Lynch’s only response was to re-affirm the innocence of the Barnetts, and to request that his property be sold to pay off his debts. He was taken back to jail, still reaffirming his innocence. Also while he was in jail Bailey and Brown (the men charged with the Frazer and Ireland killings) were put into the jail with him, and identified him as the man who had travelled into Sydney with them. That, and the property found in his possession, was enough to get them freed of the charge. Public sympathy was excited on the behalf of the remaining Frazer family – a widow, two daughters and an infant boy – and a public subscription was raised to rescue them from destitution. In the end over £115 was raised for the family. Lynch’s execution date was set for the 22nd of April, and the day before he finally decided to admit to his guilt. He made a confession to the prison chaplain, and then a statement to a magistrate. In it he confessed to all his murders, and gave many of the details above. (Many of these were confirmed later by the police – such as the fate of the Mulligans, whose bones were found at the site of an old bonfire on the farm.) His execution on the 22nd April put an end to the career of a man whose ten victims make him the most deadly serial killer in Australian history.

Images via wikimedia except where stated.

[1] Which combined natural history, morality, and alarming racism.

[2] Who nobody at the time seems to have cared about enough to record his name.