Anna Leonowens, the Chameleon of Siam

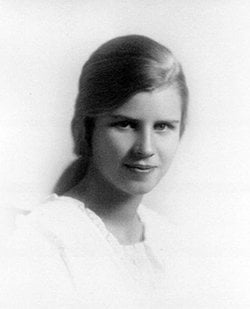

In 1862, a woman named Anna Leonowens ran a small school for the children of British officers in Singapore. She was, or so she said, the widow of a British major. She had been born as Anna Crawford in Wales in 1834, the daughter of Captain Thomas Crawford. When she was 6 her father died in a Sikh uprising, while she was at school in Wales. Her mother remained in India, and when Anna and her sister completed their education then they were sent out to join her. Anna’s mother planned to marry her off to a man twice her age, but Anna was able to avoid this by persuading a clergyman and later renowned travel writer named George Percy Badger to take her with his family on a tour of Egypt and the Holy Land. When she returned she defied her family by marrying a young British captain named Thomas Leonowens. The lived in London for a while, and had four children during their ten years of marriage. Of these the first two died in infancy, but the second two, a daughter named Avis and a son named Louis, survived. When Thomas was promoted to Major and posted to Singapore the family went with him. Anna was at this time dependent on her husband financially, as her inheritance from her father had been lost in the Indian Rebellion. Thus when he died of sunstroke during a tiger hunt she was left with no means of support, and was forced to turn to teaching to maintain herself. Then in 1862, she received an offer that changed her life.

Or rather, changed her life once again, for Anna had already changed her life herself once. The background she had created for herself in Singapore was a falsehood shot through with truths, cherrypicking those parts of her life she treasured while replacing the parts she would rather forget with a heroic fantasy. Rather than being born in Wales to a British officer, Anna had been born in India as Anna Edwards, the daughter of a British corporal. Her mother was not from an old Welsh family, but rather was the mixed-race child of a British officer and a native woman. Anna’s own mixed racial heritage was a secret she would take to the grave and beyond. Though she did return to Britain to attend school, it was in Middlesex rather than in Wales. And though it was true she had travelled with the Badger family in the Middle East, she did not marry Captain Thomas Leonowens on her return, but rather Thomas Leon Owens, a childhood friend who worked as a clerk. The couple spent the early years of their marriage not in London, but in Perth, Australia. Thomas found it difficult to find work, and Anna supplemented their income by teaching. After travelling around Australia the family eventually moved to Pengang, where Thomas died of a sudden stroke in 1859. [1] Left widowed, Anna moved to Singapore and turned back to teaching, reinventing herself in order to be a more appealing prospect to the respectable officer’s wives of Singapore. (While she was at it she shaved three years off her age, moving her birth year of 1831 to 1834, and totally cut ties with her sister Eliza’s family. [2]) Though her school was not a great success, it did serve to prove that she was a good teacher. Thus in 1862 the Siamese consul approached her with the offer of work.

King Mongkut of Siam (the country nowadays known as Thailand) wished to give his children (all 82 of them) a Western education, as he felt it would offer them the best advantage in the modern world. Unfortunately their current teacher, an American missionary named Dan Beach Bradley, was too religious for the King’s taste. He was a devout Buddhist, having been a monk before taking the crown, and had no wish to see his children convert to a foreign religion. Anna was sounded out by the consul, a prominent local businessman named Tan Kim Ching, and found to be sufficiently secular and grounded for the King’s purposes. So the offer was made, and after considering it Anna accepted. With the stipend from the royal court she sent Avis off to a boarding school in London, while she and Louis packed their bags and headed for Bangkok. Of course, the offer had been made to Anna based on the fictional persona she had invented, and so she was forced to adopt it entirely for the rest of her life. So successful was she in this that her own children grew up believing that their father had been an officer and their mother was Welsh. It would be over a century before the truth came to light.

The events of Anna’s stay in Bangkok are to this day a matter of some debate. Anna would later (as we shall see) produce her own version of events, while the Thai authorities would produce a much different one. The truth, of course, lies somewhere in the middle. The bare bones are simple enough – Anna spent nearly six years in the court, teaching the king’s children and on occasion serving as a secretary for him by writing letters in English. She was by all accounts a good teacher, and the future King Chulalongkorn, one of her pupils, remembered her fondly afterwards. She was not close with the other Europeans (mostly missionaries) in the court, though they admired her for her persistence in the face of the institutionalized misogyny and lack of respect she faced from the officials. In 1868 she took ill, and went on holiday to England to recover. Before she could return to Bangkok the King died, and his son, the aforementioned Chulalongkorn, sent her a letter thanking her for her service, and politely dismissing her from the court.

Once again without financial support, Anna headed across the Atlantic to New York. There she taught for a while, but soon found that her stories of life in exotic climes were a more profitable line of work. She began writing for Atlantic Monthly, a prestigious literary magazine with a liberal bent. This suited her temperament admirably. Emboldened by this foray into writing, Anna decided to write a memoir of her life in the Siamese court. This book, The English Governess at the Siamese Court, was a considerable success and raised Anna into the literary circle of New York writers. Though the book would face later criticism for exaggerating Anna’s role at court (as well as numerous inaccuracies) it was taken at face value at the time. The sequel, a collection of tales entitled The Romance of the Harem is even more exaggerated, and a particular detail about King Mongkut having one of his concubines tortured and executed was considered particularly objectionable by the Siamese authorities. [3] On the other hand, the portrayal of members of the harem as effectively confined slaves was a stark and welcome contrast to the often romanticised view of what was effectively sexual slavery. Taken as a piece of social fiction in the same vein as Charles Dickens, The Romance of the Harem gives a uniquely valuable perspective – a female viewpoint of the institutions that were so rarely scrutinised with empathy for those confined by them.

Regardless of the doubts around the facts portrayed in her novels, they were popular enough to get Anna onto the lecture circuit in New York. In these lectures she focused on the plight of women in these Oriental societies, though she did not neglect criticising the role of slave labour there either. In an America where slavery had been a common institution within living memory, and where women’s suffrage was becoming an increasingly heated topic of debate, her lectures struck decidedly close to home. The cash these lectures brought in came too late for her son Louis, and he fled America ahead of his debtors in 1874. Louis returned to Siam where he had grown up, and through the grace of his mother’s former pupil King Chulalongkorn received a position as an officer in the royal cavalry. In 1884 he left the royal service to start an import and export business. He married the daughter of the British Consul-General, and those connections combined with his royal friendship were sufficient to ensure his business thrived. In fact, it’s still going today as Louis T Leonowens Ltd.

In the meantime, Anna’s daughter Avis began courting a young Scottish-born stockbroker named Thomas Fyshe. In 1875 Thomas accepted a position in the Bank of Nova Scotia, which led to a temporary separation when he moved to Halifax in Canada to take up the post. Within a year he became general manager of the bank, and in 1878 he returned to New York to marry Avis. Following the wedding the two returned to Halifax. Anna taught in New York for a while, then went on a tour of the world that took her as far afield as Russia where she covered the aftermath of the assassination of Tsar Alexander II for the Boston magazine Youth’s Companion. The magazine offered her an editorial position but instead she settled in Halifax where her grandchildren were being born and where she helped establish a school of art and design. In 1893 she and Avis took the children to Germany for five years to broaden their education, and on her return Anna became exceptionally active in the suffragette movement in Halifax. In 1897 while on a trip to London she was re-united with King Chulalongkorn. The reunion was a friendly one, though the king did take the opportunity to comment on the inaccuracies in her books. By now they had been largely forgotten, however, and when Anna died in 1915 aged 85 (though the world still thought she was 82) it was her contributions to the cultural life of Halifax and Montreal (her home after 1901) that she was remembered for.

Nearly thirty years after Anna died, an American author and former missionary to Thailand named Margaret Landon published a book called Anna and the King of Siam. Margaret had heard stories of Anna while she was living in Thailand, and when she returned to the US in 1937 she began researching for the book. She enhanced Anna’s narrative with her own knowledge of Thai customs, adding a definitive sense of time and place to Anna’s occasionally dry and didactic prose. Taking some artistic license, she also added a fictionalised element of unconsummated romance to the relationship between Anna and Mongkut, as well as introducing some of the tales from The Romance of the Harem as events that occurred to Anna. The book was a smash hit, and sold over a million copies. A film was produced in 1946, and in 1950 Rodgers and Hammerstein optioned the rights to produce the musical The King and I. The musical was even more of a hit than the book, running on Broadway for three years and spawning its own film adaptation starring Deborah Kerr as Anna [4] and Yul Brynner as Mongkut. More films and adaptations appeared over the years.

Though the fictionalised version of Anna created by Margaret Landon soon became much more well known than the original, most were aware that the historical Anna was a different creature from her fictional counterpart. That the historical Anna was in many ways just as much of a fiction was not known, or even suspected, until the 1970s. The unlikely discoverer of the truth about Anna was an arachnologist named William Syer Bristowe, who originally set out to write a biography of her son Louis. When he tried to find Louis’ birth certificate in London (where Anna had told him Louis had been born), Bristowe was unable to find any record of Louis or Avis. Turning to Louis’ father, he was also unable to find anything in army records mentioning Thomas Leonowens ever having been a member of the armed forces. His curiosity piqued, Bristowe travelled to India and began an exhaustive process of research, eventually discovering the truth about Anna’s origins. Bristowe may have gone too far in the opposite direction (discounting the trip with the Badger family, for example, as another fabrication) but it was his scholarship that finally pierced a veil far thicker than any worn by the harem ladies Anna had written of. And yet, in her reinvention of her past, Anna freed herself from a social debt that would have bound her just as strongly as any of those ladies were bound. Anna was able to be the person she always wanted to be – a good mother and grandmother, who raised her voice in defence of the downtrodden, because she had seen what life under the heel could be like. May we all have the courage to be so free.

Images via wikimedia except where noted.

[1] Many thanks to reader Simon for clarifying that Thomas Owens is buried in Penang, not Singapore. Simon also pointed out that tiger hunts weren’t something that happened in Singapore – a clear mistake in Anna’s web of fictions.

[2] This may also have been prompted by Eliza marrying Edward John Pratt, who like their mother was of mixed race. Edward and Eliza’s grandson William Henry Pratt would go on to become a world-famous actor under his screen name of Boris Karloff.

[3] It’s also easily disproved in its details, as it claims the torture took place in the non-existent basements of the castle.

[4] Though her singing voice was provided by Marni Nixon, who was often employed to overdub actresses in musical roles that went beyond their talents.