Adam Worth, the Napoleon of Crime

Adam Worth, the man who would be hunted by the police forces of two continents, was born in Germany in 1844. Appropriately (since he used a fake name for the majority of his career) we don’t actually know what name he was born under – it may have been “Werth” or “Wirtz”. His father was a tailor, and the family were Jewish – something Adam generally failed to acknowledge for most of his life. “Worth” was what was written down by the immigration authorities when his family moved to America in 1849. They settled in Cambridge, just north of Boston, though the division between the two was more clearly defined than it was today. It was clear enough for Adam, who ran away to Boston in 1858. Two years later, at the age of 16, he headed to New York.

At first, young Adam was a law-abiding citizen. He got a job working in a department store, and seemed set to make an honest living. But then in 1861 fate intervened, in the form of the American Civil War. The promise of excitement, combined with a $1000 joining bonus, drew the young man to enlist. He lied about his age (he was only 17) and enlisted in the Union Army. He joined the 34th Independent Battery on October 1, signing up for a three year term. His intelligence and ambition led to him being swiftly promoted to Corporal only a month after enlisting. On May 27th, 1862 he was promoted to Sergeant. On 30th August the 34th took part in the Second Battle of Bull Run, a significant defeat for the Union Army. Adam was wounded by shrapnel, and taken to a hospital in Georgetown DC. There, according to the official records, he died on the 25th September.

Of course he didn’t actually die. There was a mistake in the paperwork, and he was listed as killed when in fact he recovered. When he found out about the mistake, Adam had a choice. He could correct it, and go back to the war, or he could take the opportunity to desert risk-free. At the time Union morale was extremely low, and men were deserting all around him. So Adam left, leaving himself listed as dead. He wasn’t done with the war, however. The army were still recruiting people voluntarily (the draft laws were not passed until 1863), and so still paid out joining bonuses. Adam took advantage of this to join and get the bonus, then leave and join another regiment under a different name. When the draft laws were passed in 1863, the bonuses ended – but they were replaced by a different incentive, where a man who was drafted could pay someone else to take his place. Those who did so, and then deserted, were known as “bounty jumpers”. Adam kept this up until 1864, when crackdowns on bounty jumpers led him to decide to get into a less risky, though no less illegal, trade.

Adam returned to New York and became a pickpocket. His tendency to avoid drinking or excess worked in his favour, and he soon began running a small gang of pickpockets and sneak thieves – he had developed a distaste for violence during his military service(s), and this line of criminal enterprise suited him. He was still a relative novice, however, and was caught stealing the cash box from an Adams Express stagecoach. For this he was sentenced to three years hard labour in Sing Sing prison. Sing Sing was a brutal puritanical prison where prisoners were forbidden to speak, and were forced to work 10-hour shifts in the marble quarries nearby. Adam was given the job of warming the frozen nitroglycerin that was used to blast the marble, and he later said:

I never questioned the guard and I always wondered why he left when I put the brittle chunks in the stove. When one of the older inmates told me I could be blown to bits, I decided I had had enough of prison.

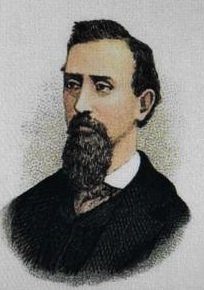

Adam escaped from Sing Sing, slipping away from the quarry during a changeover of the guards and stowing away on a tugboat he had noticed dock nearby. Once back in the city, he grew a moustache and a pair of pronounced mutton chops to change his appearance, a look he would keep for the rest of his life. This also had the side effect of causing him to strongly resemble Henry Jarvis Raymond, founder of the New York Times and prominent Republican politician. In order to maximise on this he adopted the alias of “Henry Judson Raymond”, a relative of the great man. His “front” as Raymond was financed by the profits from a job he had pulled back in his hometown of Cambridge, where he first tricked the night watchmen of a local insurance firm into granting him access by pretending to be a policeman sent to assist in guarding the premises, then used the knowledge of explosives he had learned at Sing Sing in order to break into the safe and steal $30,000. [1] He also had a patron – Fredericka Mandelbaum, a society hostess who was also a fence and criminal mastermind. It was Marm Mandelbaum (as she was known) in 1869 who gave Adam the job that would introduce him to his greatest friend, Charles Bullard.

Charles had been born into privilege – the son of a high class New York family. He had squandered his inheritance however, and turned to crime to try to recoup his fortune. He had succeeded in stealing $100,000 dollars from the Hudson River Railroad Express, by the simple expedient of bribing the guard and then pretending to knock him out. However the guard’s injury was light enough to arouse suspicion, and when interrogated he had eventually given Charles up. Marm decided to break Charles out of jail before his trial, and gave Adam and another of her employees, Max Shinburn, the job. The previous year Shinburn had helped rob the Ocean National bank of two and a half million dollars – the biggest bank robbery in history at the time. To break out Charles he and Adam once again turned to tunnelling, bribing guards to ignore the noises of digging. They succeeded, but the two men took against each other. For the remainder of his time in New York Max Shinburn and Adam Worth would be bitter rivals.

Adam and Charles, however, got along famously. The two became partners and, more significantly, great friends. They immediately set out to do a job together, and decided to rob the Boylston Bank of America in Boston, the biggest bank in the city. They bought a barbershop next to the bank and converted it into a “wine bitters dealership”, which naturally attracted no nosey customers. They broke through the wall into the bank late one night. Adam once again used his knowledge of explosives to blow the door off the strong room, and they escaped with over $450,000 in loot. However they soon heard that they were being tracked by the Pinkerton Agency, who had already discovered the trucks they used to transport the loot out of Boston. Adam knew that the infamous Pinkertons (who had also been responsible for Charley’s arrest the previous year) would soon follow the trail back to them. So they bade farewell to America and set off, as “Henry Judson Raymond” and “Charles H Wells”, for Europe.

Their first stop was Liverpool, where another significant factor entered their lives – a 16 year old barmaid (and would-be singer) from Dublin by the name of Kitty Flynn. Both men fell in love with her, and they both wooed her. Kitty was attracted to both men, and they soon formed a menage a trois – one that would continue even after Kitty married Charles. [2] Kitty was aware of the two men’s true identity, of course, but it doesn’t seem to have damped her ardour for them. When Kitty and Charles returned from their honeymoon the three moved to Paris, where they bought a three story building near the Paris Opera House and opened “the American Bar”, a combination saloon and gambling den. Gambling in Paris was illegal at the time, and so the upper story where this took place was designed to allow all the tables and devices to be folded away into the walls and concealed. Sadly one of the Pinkertons visited Paris in 1873 (either their founder Allan Pinkerton, or his son William) and decided to visit “The American Bar”. Worth realised he had been recognised, and so he and the Bullards sold the bar and left for England – reportedly stealing a bag of diamonds from a customer the night they left.

Back in England Adam used his funds to set up a network not unlike that of Marm Mandelbaum back in New York. He funded robberies, bought intelligence and bribed guards, and ensured that all the actual crimes were carried out by men who only ever worked with his intermediaries. His one rule was that his men avoid violence where possible – both a personal preference and a way to keep the heat down. These intermediaries were usually his American cohorts, who had reunited with in Paris – including Max Shinburn. Adam took 25% of the take from every job his men pulled – a low enough proportion to avoid them feeling squeezed, but high enough to make him a very wealthy man. The police soon realised that there was a single planning mind behind these criminal exploits, and the legend of this shadowy underworld figure was the inspiration for Doyle’s criminal genius, Moriarty.

Adam still pulled a few jobs himself of course, just to keep his hand in. One of the most profitable was a long con in South Africa, where he befriended the postmaster in Cape Town, learned exactly when the diamond shipments would be going through, made a copy of the man’s keys and stole half a million dollars worth of diamonds. Disposing of the loot could have been a problem, but Adam had that covered – he had one of his lieutenants set up a jewelry store in London, with bargain prices for diamond jewelry. Adam’s most famous theft, however, was of Thomas Gainsborough’s painting of the Duchess of Cavendish. It had been sold for $50,000 – the most anyone had ever paid for a work of art. One night Adam and two associates broke into the art gallery where it was on display and cut it out of its frame. The reason why Adam stole it is a mystery – one story is that he planned to use it as leverage to get his brother out of prison (though he was acquitted before that became necessary), while other stories have it that he just liked it. Regardless, he wound up keeping the painting for himself – something which caused some ill will from his accomplices, who were waiting for their cut, at least until he paid them off.

During this time Kitty had two daughters, and it’s rumoured that she didn’t know whether Adam or Charles had fathered them. Regardless of the open nature of their marriage, however, it was eventually destroyed when Charles’ first wife (who he had conveniently failed to mention) turned up in London and threatened to charge him with bigamy. By this stage Charles had become an alcoholic, so Kitty decided enough was enough, took the two girls and emigrated to New York. (There she wound up marrying a Brazilian-Irish stockbroker named Juan Terry.) Charles left London, and travelled on the continent. Adam took a wife of his own, one Louise Margaret Boljahn, who was unaware of his true identity or criminal enterprises. They had two children – a boy and a girl. The in 1892 Adam received word that Charles and Max Shinburn had been arrested in Belgium, and that Charles was gravely ill. By the time Adam arrived in the country Charles was dead.

It may have been grief for his friend that explains what happened next, or some mad impulse to prove to himself that at 48 he was still a master of his craft. He teamed up with Johnny Curtin, an American, and Alonzo Henne, a Dutchman, to rob a money transport. Though the robbery succeeded Adam was identified, and the police arrested him before he left the country. Once in custody he was identified from pictures circulated by the Pinkertons (who had been contracted to retrieve the Gainsborough painting, and who had identified Adam as the thief). He was sentenced to seven years in a Belgian prison, but he knew that this was the end of his empire.

Adam’s time in prison was not a happy one – both because Max Shinburn (who had clearly resented working for him) reportedly bribed other inmates to constantly beat him up, and because the news from outside the prison was consistently grim. His criminal empire was torn to shreds by his lieutenants, who went on to botch robberies, steal his funds, and ensure that his entire fortune was wasted. He had asked Johnny Curtin, who had escaped, to look after his wife. Instead Johnny raped her, causing her to suffer a nervous breakdown. She was committed to an asylum, and their two children moved to America where Adam’s brother John took them in. Kitty, who had read about Adam’s arrest in the papers and had sent him money and encouraging letters, died in 1894. So did Adam’s old mentor, Marm Mandelbaum. By the time he was released in 1897 (early, for good behaviour) he was a much reduced man.

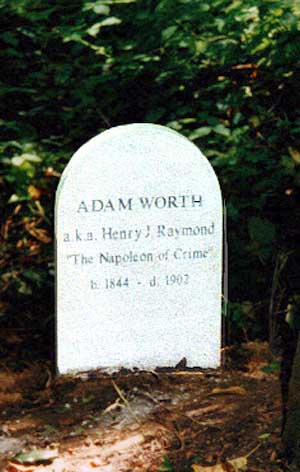

Adam returned to England, where he visited his wife in the mental asylum. Regardless of her condition when she went in, years in the hellish conditions of a Victorian madhouse had driven her nearly catatonic, and she barely reacted to his presence. So Adam decided to move to America to be with his children (reportedly burgling a diamond store to get the money for his boat passage). There he visited his children, then went to call on the Pinkertons. He still had one trump card to play – the painting of the Duchess of Cavendish. He and William Pinkerton hammered out a deal, though the details are naturally somewhat hazy. One report has it that Adam received a $25,000 payoff. All we know is that the painting was returned, no charges were filed, and Adam’s record was wiped clean. He returned to London with his children, and took an apartment in Regent Park. There he died in 1902 of a sudden illness, his health having never recovered from his imprisonment. He was buried in Highgate cemetery under his alias of Henry Raymond. A tombstone erected in 1997 gives his true name, and also gives him as an epitaph the title Robert Anderson, Assistant Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, gave him: “The Napoleon of Crime”.

One final coda. Adam left behind his two children – Henry, named for his father’s supposed name and aged fourteen, and Beatrice, aged eleven. The two were raised by there uncle John, but William Pinkerton sent them money, and wrote letters to Henry claiming to have owed a debt to his father. Whether this was part of the deal Adam and William had struck, or whether this was out of respect for a former foe, we don’t know. What we do know is that eventually Henry went to work for the very same agency that had hounded his father’s heels for so many decades – a final reconciliation with his family’s most dogged foe.

Images via wikimedia except where stated.

[1] This was his second attempt at a big score – his first had been an attempt to break into the Atlantic Trading Corporation in New York, but his younger brother John (who had joined him on the job) turned out to be so inept at the trade that he nearly had the pair caught. Adam sent his brother back to Boston, though John would occasionally work for him in the future.

[2] The modern mind might suspect that Charles and Adam could have also had a relationship, though of course nobody at the time would have suggested it.