When François Met Alfred: Dissecting the Master of Suspense in Hitchcock / Truffaut

Kent Jones’ new documentary, Hitchcock/Truffaut, tells the story of a remarkable conversation between two masters of film, and its influence on the generation of directors that followed.

Hitchcock, The Auteur

There is a tense moment on-set in Hitchcock’s 1952 drama, I Confess, when Montgomery Clift’s Father Michael Logan emerges from a police station. He knows who the killer is but is bound by the seal of confession. There’s a mob outside, waiting.

Hitchcock’s direction is clear: Clift is to pause on the steps, look at the crowd and then look up to the hotel across the street. Clift — a devout disciple of Stanislavski’s ‘Method’ school of acting — resists. He doesn’t know why his character would do that, he thinks he’d be more concerned with the mob, what they might do to him.

Hitchcock is having none of it. He needs Clift to look up so he can show the audience the hotel sign in the next shot and let them know that the hotel is very close, essential information for what happens next.

He is in no mood to humour the prima donna antics of a mere actor.

“Actors are cattle,” says Hitchcock, in his now legendary interview with French director, François Truffaut. “What? Have an actor interfere with the geography of my film?”

In Hitchcock/Truffaut, David Fincher mischievously ponders what Hitchcock would have made of the next generation of actors — a De Niro, Pacino or Hoffman — and the fireworks that might have ensued.

A Meeting of Minds

By the early 1960’s, Alfred Hitchcock was practically a franchise — his films, his television show, his books had made him a household name and the undisputed Master of Suspense. But, like Steven Spielberg, decades later, this very popularity worked against him within the cinematic establishment. To them, he was nothing more than a popular entertainer: a showman and occasional buffoon.

Across the Atlantic, thirty-year-old François Truffaut had made only three films, including one that would come to define the French New Wave movement, The 400 Blows. A serious film-maker, his mentors included highly-respected directors, Jean Renoir and Roberto Rossellini. So when the US press asked him who his greatest cinematic influence was, they were shocked to hear: Alfred Hitchcock.

In 1962, Truffaut wrote to Hitchcock requesting an interview — an in-depth, week-long series of conversations about every film he had made in his long career. Flattered, Hitchcock agreed. The resulting book, Hitchcock, presented his most famous scenes, shot-by-shot, alongside Hitchcock’s own thoughts on the making of each film.

It not only shone a light on his inventiveness and meticulous planning, elevating his reputation to that of film auteur — in Truffaut’s words, an artist who ‘wrote with the camera’ — but became THE reference book for every film-geek-turned-director who followed.

Fanboy Fandango

Kent Jones’ documentary takes us behind the scenes of the meeting, cuts Hitchcock and Truffaut’s own words with the original films, and invites today’s top directors to weigh in on Hitchcock and his influence on their own work, opening with a ‘spot-the-film’ reel of short cuts that will no doubt be a feature of movie and pub quizzes for years to come.

Wes Anderson confesses he so avidly devoured his copy of the book, it is now simply a bundle of grubby pages held together by an elastic band.

Peter Bogdanovich remembers seeing Psycho at the cinema on its release and the shocking audaciousness of Hitchcock killing the main character a mere half hour into the film: the moment when cinema audiences had all their expectations overturned and discovered film could be ‘dangerous’.

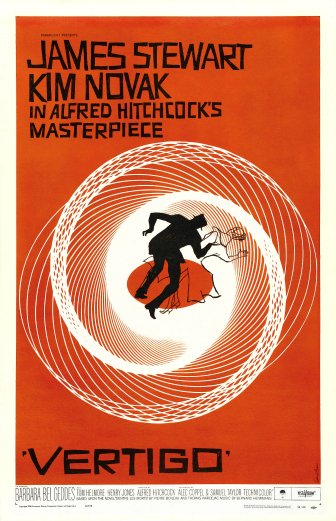

Martin Scorsese discusses the impact of Hitchcock’s Catholicism in The Birds and recalls trying to track down an 18mm version of Vertigo, at a time when such things could not simply be down-loaded from the internet. As the crucial scene rolls where Kim Novak’s character, Judy, is finally transformed into a doppelganger of the dead woman James Stewart‘s character has become obsessed with, Hitchcock dolefully explains that Stewart — turning to see her for the first time — was to convey that the character was nursing a hard-on.

Building a Reputation

Truffaut was neither a stylist nor a planner, often making last minute alterations to the script or inviting his actors to improvise a scene — the kind of spontaneity Hitchcock abhorred — but, despite their differences, he recognised the mastery with which Hitchcock used cinematic devices to deliberate effect. Over fifty hours of interview, Truffaut probed Hitch to better understand his mathematical approach to film-making, his construction of scenes and use of space, all inherited from the limitations of the silent film era, where he learned his trade; skills lost to the next generation of film-makers. He shared his findings so that others might know of Hitchcock’s artistry and learn from him.

Hitchcock’s subsequent reputation owes much to Truffaut’s serious analysis of his work.

Kent’s film has similar ambitions. In a generation where almost anything can be conjoured on screen through digital special effects, and where popular films are little more than explosions strung together with dialogue, Hitchcock’s visual innovation is still curiously compelling — a hand moving along the bannister of a staircase, viewed from above, in silent classic, The Lodger, for example — and the mastery of his construction of a film remains unparalleled. It’s about time a new generation of film fans made that discovery for themselves.

The Final Encounter

Hitchcock and Truffaut continued to correspond, to read each other’s work and offer advice, until Hitchcock’s death. It was an unlikely friendship and there’s a touching symmetry to where their story starts and ends. When the book came out in 1967, Hitchcock would make only three more films, Truffaut would go on to produce two or three films a year in a period of extraordinary creativity.

They met again in 1979, at the American Film Institute, when Truffaut introduced Hitchcock for his Lifetime Achievement award, and once again reinforced his admiration:

“In America, you call him Hitch. In France, we call him Mr. Hitchcock.”

Hitchcock died the next year, Truffaut, five years later, aged fifty-four. Between them they left behind an extraordinary body of work; together, they created the ultimate cinematic playbook and director’s bible.

Whether you’re a fan of Hitchcock, Truffaut, or cinema in general, Jones’ documentary is film geek heaven. I left desperately wanting to read the book and binge-watch every Hitchcock movie I own. Now, if you’ll excuse me, I need to grab the popcorn because The Lady Vanishes is about to begin…

Hitchcock/Truffaut is showing at selected cinemas from 4 March 2016.