Time is Luck | Michael Mann’s Miami Vice Ten Years On

Michael Mann’s film adaptation of Miami Vice is ten years old as of July 28th. It’s fair to say that Vice the movie didn’t quite achieve a stranglehold on the zeitgeist the way its television progenitor did back in the 80s. The TV show, which Mann produced for its first two seasons, was a global pop culture phenomenon that absorbed and informed the dominant look and mood of its time. Drawing on the energy and high stylization of New Wave pop music, Miami Vice perfectly captured the conspicuous consumption of the 80s, while at the same time pointing by its subject matter to the networks of dirty commerce underlying the gaudy opulence of the seafront.

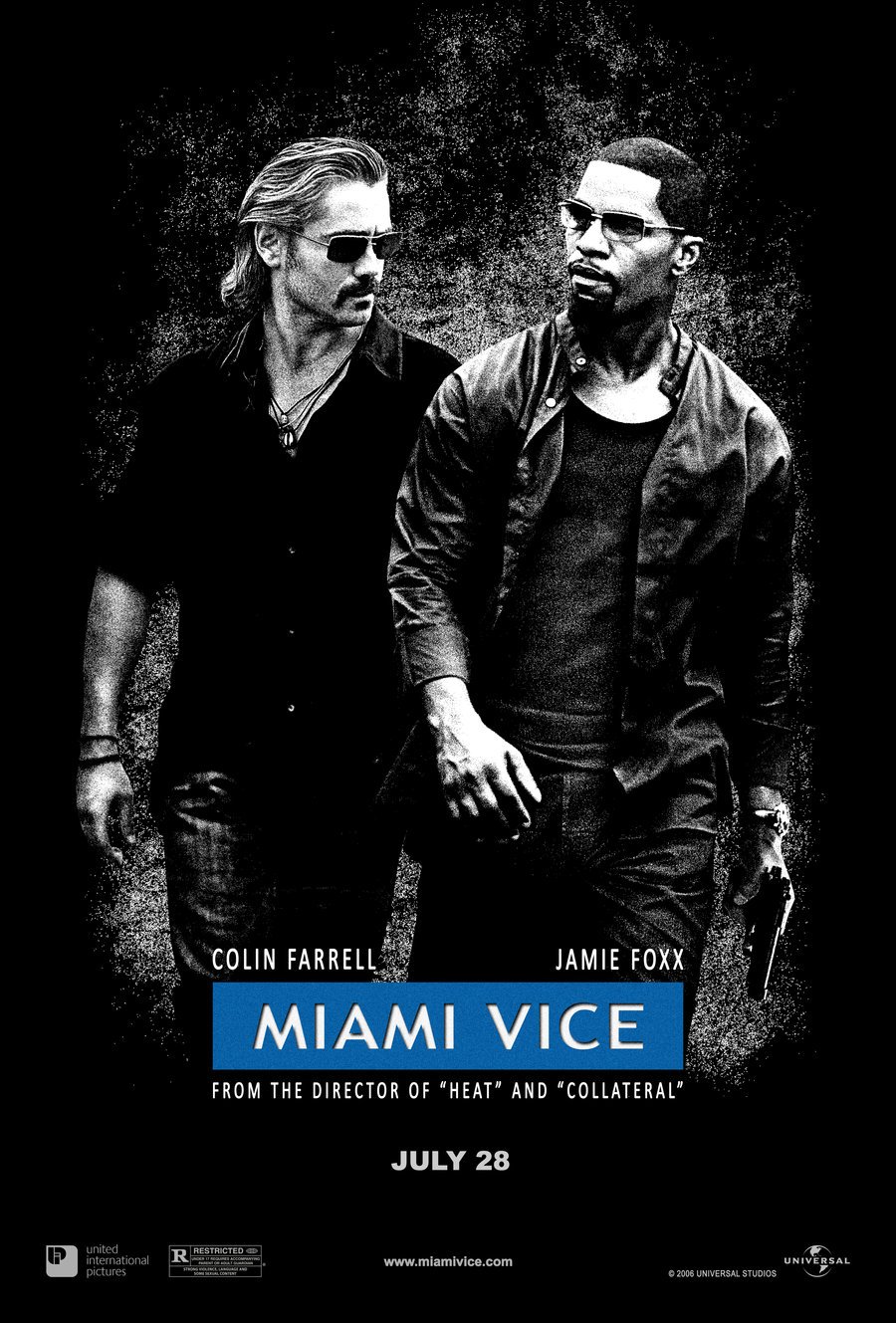

In sharp contrast, Miami Vice 2006 caused scarcely a blip. If the series had basked in the coke rush of Reagan-era mercenary adventure, the movie sulked in a post-9/11 wartime fog. Released at the tail end of July, it knocked an exhausted Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest off the number one slot, but didn’t make big money relative to its budget. Critics were divided, and audiences largely negative, bemoaning the film’s grim tone, lack of overt chemistry between its leads, and perceived lack of fidelity to its glossy source. Even long-time Michael Mann fans were baffled by the strange beast of a film Miami Vice turned out to be: the director’s once studied, perfectionist 35mm images had been replaced by noisy, smeary digital video textures, and dense characterization by figures that seemed sparsely-drawn and perpetually in motion.

Yet even while it largely vanished into the cultural ether after its release, Miami Vice has acquired a considerable cult gravitas over the years. In a 2008 Filmcomment interview, French screen icon Catherine Deneuve described a change of heart on seeing the film for a second time:

“But even so, it’s a whole other way of filming, it’s fascinating. There is a force, an incredible energy to it. His films are very long, but there are no gratuitous shots. When he decides to film the nape of an actor’s neck, there is a real tension. It’s there, it’s not at all an effect. It’s surprising. He makes you feel the weight of things.”

Writing for the A.V. Club’s Watch This series in 2013, Ignatiy Vishnevetsky called Vice a “major touchstone” for his generation of critics, and conceded watching it more times than any other film of the current century. What was it about Miami Vice that alienated so many viewers, and elicited such ardent championing among a small but vocal subset of critics? To best approach the movie, we have to first explore Mann’s very distinct approach to filming with digital cameras, and how the new medium informs his whole approach to story-telling. Most directors utilizing digital cinematography have sought to soften the transition by making digital video as film-like as possible. Even David Fincher, who exploits visual textures native to the digital medium, nevertheless produces images which are polished enough to pass as film to the untrained eye of most casual viewers.

In contrast, almost everybody notices that Mann’s films since Collateral (2004) look different. This is because the director took the opposite approach: instead of treating digital as a film substitute, Mann became fascinated by exploring digital as a completely different medium, with a different range of tones, textures and capabilities. For Mann, the primary attraction was that digital cameras could shoot in lowlight conditions with a minimum of conventional film lighting. This, combined with an increased depth of field, produced an image which was hyperreal because it lacked the familiar sense of aesthetic remove produced by theatrical lighting and the lushness of 35mm film. This new hyperreal image suggested a new relationship with time and story-telling: film, implicitly, narrates something which has happened; digital, in contrast, has the texture of capturing something which is happening right now.

This distinction, between film as a composed and narrative medium, and digital as an experiential and ‘live’ one, is crucial to understanding late Mann. All the story-telling decisions derive from this aesthetic of heightened immediacy. Characterisation and development become minimal because the characters exist entirely in the present moment, in their set of actions and reactions to a perpetual present tense achieved by hyperrealist cinematography, handheld camera work and a free, untethered style of editing. Back-story is internalized in the body language and expressions of characters who no longer seem to have the time to reflect on who they are and where they are going. They have a series of heightened experiences and impressions, rather than a story.

Few movies begin quite as in medias res as Miami Vice. The superior theatrical cut opens with a smash-cut, the only film in history that I’m aware of to do this. Seeing it for the first time, the effect is extremely jarring – you think the projectionist has missed a reel. This is the first of several gestures in Miami Vice which suggest events moving at a pace faster than our senses can adequately register.

After the smash-cut, the movie drops us into the middle of several planes of simultaneous action – a nightclub sting operation involving the chief protagonists, the home of one of their informants which has become a hostage/murder scene, and a drug-meet gone wrong between Aryan Brotherhood goons and undercover FBI agents. When the informant Alonzo Stevens (a brilliant cameo by John Hawkes) commits suicide on a roadside, we first see a POV shot that focuses on strings of paper billowing from the barriers; he then lurches out onto the oncoming traffic and becomes in a rapid cut a trail of red under a passing truck. Before we can even fully register this shock, the movie has cut again to Crokett and Tubbs on-route to his house.

This is the world of Miami Vice in its 2006 incarnation: a world moving at such terminal velocity that identity and geography are rendered diffuse and indistinct, unable to cohere in an alternatively exhilarating and alienating flurry of motion and immediacy. Time is one of the key thematic constants in Mann’s filmography. As far back as Thief (1981), James Caan’s Frank complained: “I have run out of time. I have lost it all. So I can’t work fast enough to catch up. I can’t run fast enough to catch up.” Similarly, in Heat (1995), de Niro’s Neil McCauley interprets his recurring dream of drowning as being about time running away from him. As such, Mann’s protagonists are always fighting a losing battle with time, the supreme, mystical entity in his cinema, which is always ebbing away, representing itself as an impossible ideal, an escape from the flux of professional activity, a brief interlude contemplating the ocean, or the nape of a woman’s neck.

Reflecting the accelerated pace of 21st century life, and perhaps the directors own declining years, the movement of time has become more intense, fleeting and irretrievable in Mann’s recent films. The forward momentum of Miami Vice‘s plot pauses only for a brief romantic interlude between Sonny (Colin Farrell) and cartel financial manager Isabella (Gong Li) in Cuba, an apt location as an outlier from global capitalism where time appears to stand still. All of Mann’s post-Collateral films have featured couples who seek to escape from the flux of time and the over-arching systems they find themselves enmeshed in. Sonny tells Isabella that they need to “just cash out and get out”; in Public Enemies, Johnny Depp’s Dillinger dreams of “sliding off the map” after a few more scores; only Chris Hemsworh and Tang Wei appear to attain this goal of escape and invisibility after they elude a surveillance check point and vanish into digital noise in the final frame of Blackhat.

Miami Vice, in contrast, ends on a note of pure noir fatalism and futility. The undercover operation is largely a failure: some low to mid-players are killed or injured on both sides, but kingpin Archangel de Jesus Montoya remains elusive. Their fabricated identities and “what’s really up” having “collapsed into one frame”, Sonny and Isabella are forced to resume their respective sides of the law, with Sonny returning with a weary thread to the trenches of an unwinnable drug war. The film cuts to black as abruptly as it exploded into existence, still in motion and in medias res.

Miami Vice is far from perfect, but in some respects it achieves something more intoxicating and alive: a sense of cinema looking and feeling unlike it had ever done before. Mann had achieved a level of insurmountable perfection with 35mm film and classical storytelling with Heat and The Insider in the 1990s; Miami Vice in contrast is charged with a sense of reckless adventure and discovery, the excitement of a director searching for a new cinematic grammar, capturing rich, ambient textures of light, nocturnal skies and city scenes so immediate and tangible they feel like a lucid dream.