Literature on Film | 16 | J.G. Ballard’s High Rise as Adapted by Ben Wheatley

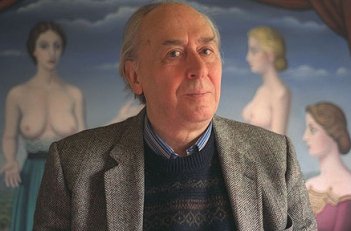

When we look back at 20th century literature, there’s an interesting, recurring aspect that runs through the work of the authors lucky enough to have been afforded their own adjective. The novels of George Orwell (Orwellian), Franz Kafka (Kafkaesque) and J.G Ballard (Ballardian) are works that often thrive on nihilistic disarray, offering us chilling, oppressive dystopias that paranoiac figures try and will fail to navigate. There is a key difference however: While Kafka and Orwell both feared the soulless, dehumanising nature of labyrinthine bureaucracies, Ballard was far more concerned with chaotic worlds that existed when these fragile social structures inevitably collapsed. His characters are often complicit in the societal breakdown, as they revert back to their primitive selves and revel in the animalistic anarchy that they were always destined to revel in.

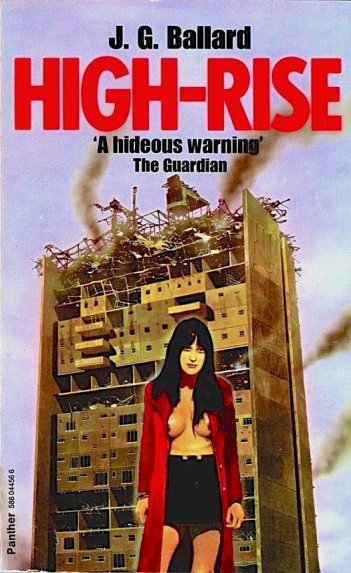

His best and most representative novel High Rise sets itself inside an ultra-modern (for 1973), self-sustaining tower block that’s been designed by an ageing ideologue and architect.

”Before long the social experiment devolves into primordial mayhem; it’s isolated, well to do inhabitants fall prey to their lustful cravings and repressed tendencies for barbarous behaviour.” Instead of this opulent, insular lifestyle becoming a new high standard for living, the luxurious amenities and seemingly limitless floors end up as nothing more than arenas of destruction. With its “forty floors and thousand apartments, its supermarkets and swimming pools, bank and junior school – all in effect abandoned in the sky – the high-rise offered more than enough opportunities for violence and confrontation”.

A derision of the feigned etiquette of middle England and the fragile nature of societal stability, High Rise was a prescient cult novel that predicted the rise of late 20th century urban disillusionment.

When it was announced that a long-in-the-works film adaption would eventually be produced, there was collective sigh of relief among ballardians when it was revealed who would helm the director’s chair. The reliably depraved Ben Wheatley feels like a perfect match for the writer’s sardonic outlook. More than any other director currently working, Wheatley might be the one with the most “Ballaridan” worldview. Like Ballard, his worlds are ones completely devoid of any semblance of human decency: There’s the distrusting, dysfunctional family of criminals in Down Terrace, the murderous vacationing couple of Sightseers and the chilling, wicker man like cult in Kill List. These films may offer sporadic acts of bone crunching violence, but it’s the volatile, unpredictable and morally debased characters he utilises that makes the works truly unsettling.

On paper it would seem the perfect fit but that’s rarely how these things pan out. Adapting a novel like this was never going to be an easy task and the 2016 film version ends up as a mixed bag of an enterprise. Ben Wheatley’s effort is a sleek, stylised effort with an A list cast that includes the likes of Tom Hiddleston, Sienna Miller, Elizabeth Moss and Jeremy Irons but in adding this slightly spurious sheen to the proceedings, something is lost along the way. If nothing else, it’s an interesting blend of the distinct styles of two artists who excel in perversion. Wheatley’s problem, however, is that he has produced an adaptation that is somehow both too faithful to its source, but also not faithful enough. While not a complete failure by any means, High Rise the film can’t quite manage to replicate the source material’s sense of utterly ruthless and reckless abandon.

There is no doubt that Wheatley has an eye for flair and that the film looks the part. The towering image of the brutalist skyscraper that graces the stratosphere, the pristine, eerily homogenous aisles of the antiquated supermarkets and the big brother rhetoric coming out of the ligneous TV sets: 70 kitsch has never seemed so foreboding. A lot is also owed to Clint Mansell’s typically stupendous soundtrack, which is sinisterly playful with a hint of winking irony. There are even two re-purposed versions of Abba’s S.O.S., one orchestral, one a haunting cover by Portishead, that turn the Swedish super group’s panicky words in to a desperate plea for escape from the metropolitan claustrophobia.

The film version is mostly a sincere retelling but attempting to follow the same narrative beats of the book might be a mistake. Ballard’s story is a fractured one that hops around between the three central male figures who each fall victim to their hubris or carnal behaviours: The psychologist Dr. Robert Laing, The beastly Richard Wilder and the building’s narrow minded, elderly visionary and designer Anthony Royal. In the novel, the disastrous events (a dog drowns, a man falls off balcony, residents rampage) go by thick and fast without much time to process them, making it a fittingly disorientating descent into a hellish nightmare. Wheatley attempts the same thing, but it makes it all a bit ponderous. He gives us no time for the scenes to make a lasting impact, and the film feels like 20 minutes longer than it actually is. It’s all a bit flat, and there nothing as impactful as the blood curdling final moments of Kill List here.

Another issue is that Ballard’s characters just simply don’t have much character. Hitchcock once famously referred to actors as to little more than “cattle” and Ballard might have a similar sentiment towards his creations. The people in his books are mere instruments to play with, bit players and simply symptoms of a sickness that pervades wider society. Wheatley, keeping to the book again doesn’t really develop these figures any further. Hiddleston’s Laing is given a more central role but not much more to do and he somehow ends up being only more listless. A talented actor yes, but it’s a talent that’s lost in the supercilious slow motion. Luke Evans is the only one who really excels as Wilder, in a meaty role in which he gets better as the character becomes increasingly paranoid and inhuman.

What is perhaps Wheatley’s most fatal mistake, however, are his attempts to turn High Rise into a work of political commentary. Although he certainly understands elements of Ballardian anarachy, the director also appears intent on adding a class-conscious critique to the proceedings. Consider the painfully on-the-nose sequence early on in which Laing attends a pompous, haughty party thrown one of the higher floors. The snotty revellers are even wearing garb akin to those worn by the French aristocracy of the late 19th century. It’s not exactly subtle. This is not the prism in which the original author saw the world from. Ballard endured a difficult, at times brutal, upbringing in which he was forced to mature long before most boys his age. The son of a wealthy British expatriate in Shanghai, young James Ballard came into contact with the horrors of humanity early on when he witnessed, first-hand, the invasion of China by the Japanese forces in the late 1930s. The war meant he spent much of his formative years in an internment camp for westerners.

Those years of close quarters imprisonment and of widespread cruelty, not only informed his outlook but also surely coloured the savagery found in his writing style. In an interview at the end of my copy, Ballard states as such:

“The experience of spending years in camp as a boy, taking a keen interest in the behaviour of adults around him, including his own parents, and seeing them stripped of all their garments of authority that protects adults generally when they’re dealing with children, to see them stripped of any kind of defence, being humiliated and frightened—and we all felt the war was going forever and heaven knows what might happen in the final stages—all of that was a remarkable education. It was unique and it gave me a tremendous insight into what makes up human behaviour”.

For Ballard, the choice of using a luxury housing development like this one as a microcosm for the inevitable ills of human nature was deliberate and timely. In the early 1970s the tower block would have been seen as the apex of modernity in Britain, so having all hell break loose in the same place where people would put up their puke-inducing floral wallpaper made his point all the more salient. Humanity’s attempts to repress it’s war torn recent past would also be fruitless in the end . Wheatley’s politicisation is a misstep for this reason as it loses the sheer fatalism of it all. Seeing a bare arsed Tom Hiddlestone covered in Dulux war paint has all the politically motivated edge of the image of a Che Guevara T-shirt on sale at Penny’s.

The final shots of the film are the most irksome. After the mass pandemonium, multiple deaths and social self-destruction, the novel concludes with Laing looking out from balcony at a new “high rise four hundred yards away” as just like with his residence, he notices the “temporary power failures” as the “residents made their first attempts to discover who they were”: “Laing watched them contentedly, ready to welcome them to the new world”. Wheatley concludes his version in a similar vein – with Laing reflecting on the fate of the second high-rise – albeit with one exception, the last images are given to a pointless child character who is listening to an infamous speech by Margaret Thatcher in which she states “Where there is State capitalism there will never be political freedom”. Aside from the fact that using the naive words of a controversial politician while showing civil disorder (it’s ironic, get it?) is like drawing from a well so dried up one wonders if there was ever water there, this again just misses the point.

Wheatley’s attempts to make the collapse of life in the high rise into some sort of visual polemic on the rise of Thatcher’s brand of populism does a disservice to Ballard’s apolitical, joyless pre-determinism. In the final pages of the novel, we can see the irrepressible images of war rear its head in the writing as the civilisation reaches utter desolation in an empty swimming pool of a tower block:

“In the yellow light reflected off the greasy tiles, the long tank of the bone pit stretched in front of them. The water had long since drained away, but the sloping floor was covered with skulls, bones and dismembered limbs of dozens of corpses. Tangled together where they had been flung, they lay about like the tenants of a crowded beach visited by a sudden holocaust”

This is a writer who, knowing full well of the lengths to which humanity can degrade itself, saw a universe that was only governed by chaos and disorder. For Ballard, no matter the degree to which nations rebuilt themselves, political stability appeared to endure or peace treaties were respected, mankind was always and inevitably going to revert back to its destructive and brutal nature. Ben Wheatley’s High Rise is far from a failed adaption, but I just wish it was a fearless one.

Featured Image Credit