Literature on Film |19| The Silence of the Lambs Lays the Groundwork for Psychological Horror

Few films can boast the ripple effect that The Silence of the Lambs lays claim to. On the one hand, it introduced us to one of modern cinema’s greatest villains and a universal pop-culture shorthand for derangement in Hannibal Lecter (Anthony Hopkins). By extension this laid the groundwork for endless copycats and a whole new quirk for movie villains that we still see today: this is apparent whenever we see a bad guy end up psychoanalysing a protagonist from the wrong side of a transparent cell. In fact, Kim Newman has an excellent chapter in Nightmare Movies outlining the shadow Lecter cast over cinema in the 90s and beyond.

The film can also boast having inspired practically a whole genre of television; the deluge of female-led crime procedurals, both gritty and supernatural, that followed in Clarice Starling’s (Jodie Foster) wake are a testament to the legacy of the film’s initial popularity. The story of a young FBI recruit enlisting the help of an incarcerated psychopath in a race against time to save the latest victim of an ostentatious serial killer feels positively passé these days. Still, you’d be hard pressed to credibly argue that there isn’t a healthy dose of Lambs in the DNA of shows like The Blacklist or Fringe even if it’s just a jumping off point.

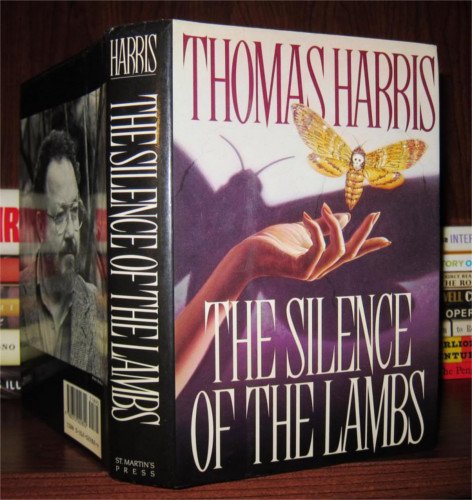

But what of famously reclusive author Thomas Harris’ novel? Lecter as played by Anthony Hopkins has always felt like an inherently cinematic creation – a character whose visual and aural traits seem so identifiably at home onscreen that it’s difficult to picture him exclusively on paper. Nonetheless that’s from where he hails and this book wasn’t even his first appearance (that honour of course goes to Harris’ previous novel Red Dragon). While fans of the books may debate the authenticity of Hopkins’ portrayal, it is generally accepted that Silence of the Lambs is one of the most faithful book to film adaptations that one could cite. Smaller details are lost and some characters like Jack Crawford have their roles heavily reduced but the tone and mood remain intact, the central characters are as engrossing onscreen as they are on the page, and Harris’ feminist narrative is translated masterfully to the screen by Jonathan Demme’s Oscar-winning direction.

While both book and film indulge in slightly heightened versions of reality, the particulars differ. The film’s is more aesthetics-based with its stylised, gothic set design and locations; however memorable and visually interesting you find Lecter’s prison, there is no psychiatric institution on Earth that looks like the dungeon below Dracula’s castle the way Baltimore State Hospital for the Criminally Insane from the film does. In the book meanwhile, it’s Harris’ penchant for taking a more Bond-villain approach to his antagonists than any of the films would truly imply; imbued as they often are with cartoonish deformities and wearing their other-ness on their sleeves – if you thought Gary Oldman’s Mason Verger from the sequel Hannibal was as monstrous as they came, Harris’ version on paper is somehow even worse; a immobile child’s-tears-drinking, almost melted Jabba the Hutt-like figure.

While Hopkins plays Lecter with a pantomime flair and eccentricity not entirely present in the cold, calculating, clinically psychotic Hannibal of the initial books, the movie still grounded other aspects better than its source material. For example, Lecter’s possession of a fully functioning sixth finger on one of his hands. This was unsurprisingly removed via surgery between novels for Hannibal as it was a tad of a giveaway for one of the FBI’s most-wanted on the run. Not to mention of course his literal red eyes. While these are the sorts of things you’d expect to not make the cut, it is amusing to imagine how Hopkins’ Oscar-winning performance would have looked had he been chewing his way through scenery with the addition of red contacts and a goofy-looking prosthetic.

Character-wise the film is both an excellent portrayal of the book’s Lecter while simultaneously being the Anthony Hopkins Show and ultimately the performance that would inform future interpretations of the character on-screen and in print. To an extent Hopkins played up the polite, rudeness-hating aspects of the character too much. This works fantastically for the second half of the film where his horrific murder of those guarding him feels all the more graphic in light of how pleasant he’d seemed up to then; reminding the audience that there was a reason this man had been locked in a windowless cell underground for so long. (Not to mention introducing the idea of Lecter making depraved tableaus of his victims, something which Brian Fuller would go on to milk three seasons of TV from.) But within the books Lecter has a petty, crude streak running through him that bubbles up from time to time. Like when he refers to Buffalo Bill’s (Ted Levine) attempts to create a female skinsuit as making “a vest with tits on it” simply to upset and anger Clarice. It’s not hard to imagine either Brian Cox (no not that one, that one) or Mads Mikkelsen’s Hannibal spitting out that line, yet it would seem oddly out of place with Hopkins.

Clarice too translates largely intact between mediums. While the novel gives greater focus to her internal struggles to deal with the sexism and misogyny she faces and sees every day, not to mention her attempts to bring her rage into check, the film, by virtue of not being Lynch’s Dune – that is, not being a film foolish enough to contain oxymoronic, out-loud internal monologue – is more externalised in its focus. This is where credit to Demme for his unusual direction is most due.

The near constant close-ups, many of which act as Clarice’s POV, are unsettling and intense, reminding us how much she’s stared at, judged and sized up by almost everyone she meets, echoing Lecter’s line “don’t you feel eyes moving over your body, Clarice?” This is further reinforced by some slightly over-zealous background work from the featured extras that, while keeping with the theme, come across almost farcically sexist once you start to notice it. (Special credit to the guy that almost walks into Foster without breaking his intense stare during the shot of her walking through the airport.) Extras will of course be extras but Demme does do a good job of conveying the feminist overtones visually. Simply look at the early shot of Clarice entering the elevator full of male FBI trainees: Foster’s tiny frame is towered over by these hulking brutes yet her head is held high and body language relaxed, conveying that despite the uphill battle she faces, she’s not willing to cower before it.

It would be remiss in this otherwise slightly gushing analysis not to briefly touch on something the film (and to a much lesser extent, the novel) have been marked by: the long held accusations of homophobia and transphobia. While it is unfortunate that Bill has gone on to typify what many see as a blatant example of cinematic transphobia, both the film and book go to lengths to emphasise that this isn’t the case. Sadly, the very nature of adaptation, and film editing, works against this in the movie: with the film, as is, we have little beyond a couple of exchanges between Lecter and Clarice where, despite Lecter literally saying Bill isn’t a real transsexual, Clarice reinforces this point and a major plot point hinges on it. These are ultimately single lines of dialogue scattered sporadically through a dialogue-heavy film.

The book handles this better by the very nature of its medium, as all dialogue gets equal attention along with some additional scenes of clarification (at least one of which was shot but cut for time). From a cinematic point of view, it’s easy for people to miss some quick lines of dialogue but less easy to forget the image of Ted Levine mincing around in make-up, wearing the scalp of a female victim and ‘tucking’ while that song plays. It’s not hard to see how the initial backlash came about. Still, as Christopher Schultz states, the “narrative suffers from an error of omission rather than intent” (Schultz’s article gives a detailed and very fair analysis of the controversy as it is a muddled issue, and one that could warrant its own separate discussion far outside the scope of this one).

In this day and age there’s no shortage of similarly structured crime thrillers in either book or film but if you’ve seen and enjoyed (or perhaps even if you didn’t enjoy) the film, the book is well worth your time. Like its multi-Oscar-winning adaptation, the book is simply an incredibly well-crafted thriller with a more intellectual slant than most and with some unexpectedly intense moments of horror. While for my money, the uneven and detrimentally self-indulgent sequel is more fascinating due to how unusual it is (the full extent of which we’ve yet to properly see adapted on-screen despite two different attempts), Lambs is easily the pinnacle of the Lecter saga both cinematically and literarily.

[youtube id=”W6Mm8Sbe__o” align=”center” autoplay=”no” maxwidth=”750"]