Director Profile | The 5 Essential Films of Sergio Corbucci

In recent years, there has been a resurgence of the Western genre. 2016 has given us already The Hateful Eight, Bone Tomahawk, The Revenant and Jane Got a Gun. This month sees the release of two other significant oaters – Hell or High Water and The Magnificent Seven, while Andrew Dominik’s 2007 masterpiece The Assassination of Jesse James enjoys a re-release in select art-house theatres. To pay tribute to the genre, this director profile will focus on Spaghetti Western pioneer Sergio Corbucci. Although undisputedly a B-movie filmmaker (which is why he is overshadowed by his more artistic contemporary Sergio Leone), Corbucci’s movies, at their best, transcend their roots in exploitation cinema. Being a left-wing radical, the Italian director injected a lot of political allegory into his work while subtly challenging the rules of the Westerns which proceeded him, perhaps most notably in his penchant for downbeat endings. As I analyse five key films by Corbucci, I will highlight the contribution he made to the Western genre, the surprising and subversive elements of his work and the influence he had upon many modern directors.

Django (1966)

By the time Django was released, Corbucci had already made many movies, including the Western Minnesota Clay (1964). However, it was his iconic 1966 film starring Franco Nero as the titular character – a wandering gun-slinger carrying a coffin who becomes entangled in a feud between the Confederacy and Mexican revolutionaries – that brought Corbucci fame.

Inspired by Akira Kurosawa’s Yojimbo (1961) and Sergio Leone’s A Fistful of Dollars (1964), Corbucci employs much of the genre iconography that originated from those movies e.g. guns, coffins, an unnamed stranger, rival gangs. However, Django plays like a more rebellious cousin to these films. Corbucci’s radical left-wing politics are evident in how the two figures of authority within the story, the Confederate Major and the Mexican General, are both portrayed as sadistic villains, whereas the drifter in the black hat (typically seen as the sign of a bad-guy in old Westerns) is an agent of peace and change. As Luis Bacalov’s brilliant theme tune states, after Django: “the sun will be shining”.

[youtube id=”4_OiUURbYlQ” align=”center” autoplay=”no” maxwidth=”750"]

The film is also much more violent than the Westerns that came before. According to IMDB, Django has a body count of 180. It begins with a woman being brutally whipped, has a long sequence in its middle where over 70 men are killed by a retro-machine gun (it shares with Yojimbo a theme regarding the rarity of guns in a period setting) and ends with a gunslinger having his fingers broken (a metaphor for castration which reoccurs throughout Corbucci’s filmography). It’s no surprise modern filmmakers Takashi Miike and Quentin Tarantino, both known for ultra-violence, have directed homages to this movie – Sukiyaki Western Django (2007) and Django Unchained (2012). Tarantino even credits the infamous ear-cutting scene in Reservoir Dogs to a moment in this film.

Navajo Joe (1966)

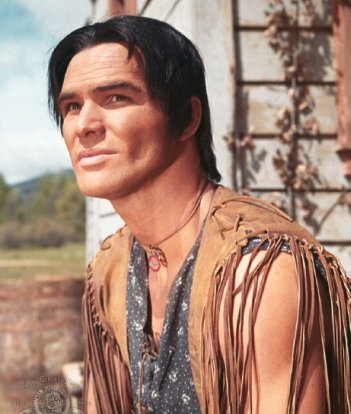

Corbucci followed Django with the lesser, on account of some racist casting, but still enjoyable Navajo Joe. Wearing a wig that made him look like Natalie Wood, Burt Reynolds stars as the titular Indian (yes, really), a man seeking to avenge the scalping of his tribe by the outlaw Duncan (Leone regular Aldo Sambrell). He follows Duncan into a nearby town, where the criminal is hired by a shady town doctor to rob a train. Joe, learning of this, begins to interfere with the heist.

If one can get past the casting of Reynolds, there is a lot to love about Navajo Joe. Even though an American actor is playing the role, it’s great to see a Native American at the centre of a Western, instead of stereotypically being represented in the side-lines like in the cowboy movies of old Hollywood. Corbucci implements a few striking directorial touches. For instance, the face of the doctor who hires Duncan is obscured by items in the frame. This makes a later scene, in which a witness to Duncan’s actions is treated for a gunshot wound, all the more tense, because we’re unaware whether the man nursing her is actually in cahoots with the outlaw. The cinematography by Silvano Ippoliti (who went on to work with Tinto Brass) is amazingly vast and expansive and the ending has a melancholy which is sudden but touching. However, without a doubt the most praise-worthy aspect of Navajo Joe is Ennio Morricone’s incredible score. Blending choral voices, Native American music and the sounds typically heard in spaghetti Westerns, Morricone created a soundtrack still sampled to this day in movies as diverse as Alexander Payne’s Election, Kill Bill and Me, Earl & the Dying Girl.

The Mercenary (or A Professional Gun) (1968)

After directing two more Spaghetti Westerns (The Hellbenders (1967) and Death on the Run (1967)), Corbucci tackled a Zapata Western. This sub-genre is a variation on the typical Spaghetti Western, whereby the films are set in Mexico and feature more overt political themes. The Mercenary centres on the uneasy alliance between dim-witted revolutionary, Paco (Tony Musante), and Polack (Franco Nero), a mercenary in his employ. As the aspiring leader rises in power, his recklessness puts the two in danger, creating an enemy in Curly (Jack Palance), a rival merc to Polack.

Due to his roots in exploitation, Corbucci was very good at giving his audience exactly what they desired. Although The Mercenary features many artistically striking visuals (a shootout during a Day of the Dead festival, a silhouette of Jack Palance riding his horse against a setting sky), Corbucci doesn’t let five minutes go by without a funny or inventive action sequence taking place. These include a fight scene between Paco and Polack, where the former throws a pigeon coop or a moment in which Polack shoots a barrel full of water, creating a retro shower for himself. These moments, although undeniably silly, do lend a charm to this film – which became the blueprint for the director’s infinitely better, next stab at the Zapata picture. Also, worth noting within The Mercenary is Corbucci’s homage to the iconic stand-off scene from The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (picture above)

The Great Silence (1968)

Undoubtedly Corbucci’s best film (with Django as a close second), Tarantino’s The Hateful Eight is more heavily influenced by this than Django Unchained is of Django. Although the American director’s 2016 film has a completely different plot, it cribs its blizzard setting, a moment where a character urges another to pick up a gun – so they can kill them and claim self-defence, its theme regarding the clash of frontier justice and “civilised” justice and its method of having its three lead characters meet via carriage ride all from Corbucci’s movie. Set in 1898, The Great Silence takes place in the time where bounty killings were beginning to become outlawed. However, Pollicut (Luigi Pistilli), a corrupt justice of the peace still enforces the law, using his position in society to hire the crazed hunter, Loco, (Klaus Kinski) to kill his enemies. His actions put the two in conflict with the central hero, Silence, (Jean-Louis Trintignant), a mute gunslinger whose family were killed by Pollicut, and a new Sheriff (Frank Wolff), who is anti-bounty killing.

The Great Silence’s astounding snow-bound setting and Ennio Morricone’s almost horror-esque score set it apart from any Western of the era. Corbucci’s direction has never been more stylised. A moment whereby the film flashes back in time by linking the image of a candle burning in the present to one in the past is pure genius. Working with an international cast of actors, the performances are exceptional. Trintignant puts in a surprisingly vulnerable turn in an archetypal role typically played with icy coolness by Clint Eastwood. This is then countered with mesmerizing work by Kinski playing an occasionally charming but ultimately crazed character.

The Great Silence also features the left-wing radicalism of Django, and to a lesser extent Navajo Joe. Pollicut is a justice of the peace who employs murderers and is shown to have sliced a child’s throat to prevent him identifying the killer of his family (the reason for Silence’s mutism). Again, it’s the outsider who is the hero, taking revenge on the bad guys not by killing them but by shooting off their thumbs, preventing them from using another gun (another psychoanalytic image). I couldn’t end a piece on The Great Silence without addressing its overwhelmingly bleak and pessimistic final moments. As the majority of Westerns have happy endings and the ones that don’t generally have heavy shades of hope, it’s shocking and memorable to see an oater so vehemently go against this trend.

You can watch the full film here.

Compañeros (1970)

Often cited as the director’s The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, Compañeros was Corbucci’s second and best take on the Zapata Western. Reuniting with Ennio Morricone (another phenomenal score), Franco Nero and Jack Palance from The Mercenary, the movie revolves round a similarly uneasy partnership. Vasco (Tomas Milian), a patsy for a greedy army general, is forced to team up with his boss’ weapons dealer, Penguin (Nero), to locate the idealistic revolutionary Prof. Xantos (Fernando Rey).

The movie feels like the work of a director aware of their skill and possessing a confidence to let loose in their indulgences. The longest movie on this list, Compañeros functions equally well as a politically charged actioner for which Corbucci is well-known (Vasco’s army general is shown as a coward – appointing peasants to high-ranking positions for dangerous missions and then showing up post-battle to receive the credit) and as a tremendously entertaining buddy-comedy. The chalk and cheese pairing of Milian’s uneducated and ill-advised peon (who is essentially the same character Musante played in The Mercenary but performed much better) with Nero’s suave but eccentric gun merchant blends perfectly for maximum comic effect.

[y[youtube id=”kS3xHRUuoKI” align=”center” autoplay=”no” maxwidth=”750"]p>

The world of the Compañeros feels better fleshed out than Corbucci’s previous movies, perhaps on account of its colourful supporting characters and cast. The film’s structure, centring upon a journey, enables its leads to keep moving from one bizarre situation to another. Case in point, Jack Palance chews the scenery memorably as the one-handed, falcon-wielding villain with a vendetta against Penguin. However, while this may sound too pulpy, Luis Bunuel regular Fernando Rey adds a touch of grace to the film, always reeling it in with his philosophical musings regarding revolution and violence before the movie becomes too unruly.

Arguably, Compañeros was Corbucci’s last great film. Following this, he directed a few less successful oaters before leaving the old West behind, transitioning into comedy. His later movies, although box-office successes, didn’t gain Corbucci admiration from critics, who generally regarded him as a director for hire lacking artistic vision. However, it’s clear from analysing these films that the filmmaker had an undeniable authorial stamp. Without him there would be no Rodriguez (the El Mariachi trilogy owes so much of its success to Django) or Tarantino and the landscape of modern cinema would look significantly different.

Order to watch the five films

- Django

- The Great Silence

- The Mercenary

- Compañeros

- Navajo Joe

Also worth checking out

Corbucci directed 63 films in his lifetime – working in other genres ranging from sword and sandals fantasy to horror to parodies of classic Italian cinema. However, if one is only interested in his Westerns, there are plenty of other renowned directors from that time who released similar output including Sergio Solima, Damiano Damiani and Enzo Barboni.

Featured Image Credit