David Bowie | From the Ridiculous to the Sublime

Blackstar, David Bowie‘s final album, a curious mix of free jazz, Nadsat and Death Grips, had surprisingly little buzz surrounding it in the build up to its release. Had Neil Young or Bob Dylan or Tom Waits announced that they were releasing a record that was influenced by industrial hip hop, everybody would have tuned in, if only to see the resulting car crash.

With Bowie though this hardly raised an eyebrow, because such weirdness is almost to be expected. This isn’t to imply that Bowie is only weird in relation to everybody else-which he most definitely was-but that he was weird in relation to himself, shedding and pursuing musical identities with reckless abandon.

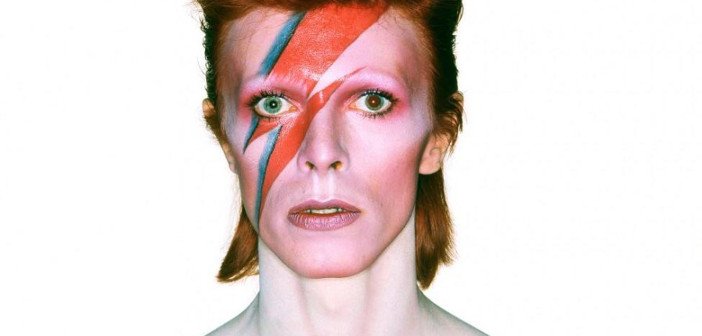

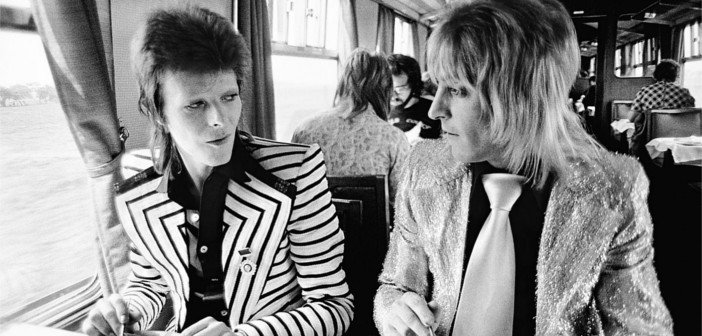

His first hit, ‘Space Oddity’, ostensibly a novelty folk song to cash in on the moon landing, dealt with alienation, despair and doomed romance. On Hunky Dory and The Man Who Sold the World masculine, heavy rock was matched with a bitchy androgynous image and his lyrics traded sex, drugs and rock and roll for Alastair Crowley, Frederich Nietzsche and Andy Warhol. He elevated glam rock to high art by infusing it with beat poetry, science fiction, queerness and mime. This pre-empted punk by about three years, and indeed it was Bowie’s circus that gave Iggy Pop, Lou Reed and William S. Burroughs a gateway into popular culture. At the height of glam rock stardom Bowie exiled himself to America. On Young Americans and Station to Station he replaced flamboyant glam rock with cold mechanical funk and Ziggy Stardust, Aladdin Sane and Halloween Jack where out. The Thin White Duke, a downright nasty lounge lizard, was in.

He flirted with cabaret, a pretension that spat in the face of punk. Subsisting for a year entirely on peppers, milk and cocaine Bowie’s American adventure nearly killed him. He retreated to Berlin and embraced Can, Neu and Tangerine Dream. Low and Heroes sound like a man waking up after a long sleep, and there wide eyed optimism was out of step with punk’s angry urgency. Having spent a decade giving a voice to freaks and outsiders, Bowie then made a bid for mainstream stardom. Had Let’s Dance and Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps) not been so much fun, this could have come across as a crass betrayal. In the 90s when glam rock was fetishised by Britpop acts like Blur, Suede and Pulp Bowie refused to cash in, trying his hand at industrial, and refusing to play any old hits when he toured with Nine Inch Nails. Similarly, The Next Day, a comeback record of sorts, made it clear that it wasn’t a nostalgia run by literally desecrating the Heroes iconic cover.

What lay underneath Bowie’s fearlessness about musical experimentation was a similar fearlessness about pushing social boundaries and conventions. In the guise of the alien rock star Ziggy Stardust he appeared on top of the pops in make-up and drag, regularly fellated Mick Ronson’s guitar and came out as bisexual. For 1972, this was something otherworldly. Homosexuality had only been decriminalised five years (Ziggy’s opening track, by coincidence) prior. Ziggy was pop’s first star that urged us to just “lose it”, to just have a good time, to ignore convention on gender or sexuality, because the world would be a much better place if you just did what made you happy. Halloween Jack, the gay rock and roll pirate on Diamond Dogs, framed this as an actual rebellion, urging everybody to embrace weirdness in the face of bland normalisation. Nearly 40 years on, this attitude still seems ground breaking. Needing peace and quiet to ween himself off drugs, Bowie moved to West Berlin, which was in the grip of Cold War tensions, with Iggy Pop, who was in the grip of a heroin habit.

Considering that fear of the “other” is creeping back into society and that thought crime is slowly becoming a reality, what with constant reminders to watch what we say online and to each other, Bowie’s efforts to constantly broaden his horizons and the force of will to live life on his own terms isn’t just interesting-it’s remarkable. It’s become painfully apparent over the last few days that Blackstar, Bowie’s latest re-invention, was to explore death. Pitchfork’s review, posted three days before his death opens eerily with the line “David Bowie has died many deaths, yet he’s still with us”, and concludes by noting that Bowie’s latest masterpiece was “adding to the myth while the myth is his to hold”. Tony Visconti went so far as to say that Bowie’s death was a work of art. Considering he spent his career breaking taboos this is probably the highest compliment anybody could pay.

Even in the wake of his passing, it’s clear that the myth of David Bowie will always belong to David Bowie.