War in a Time of Games | Spec Ops: The Line

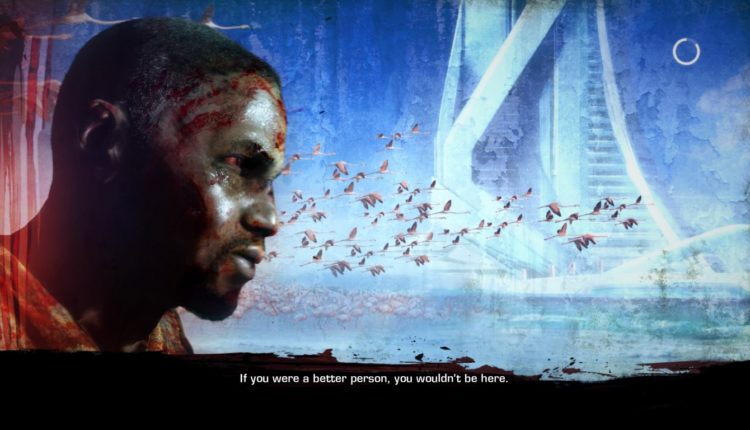

“Do you feel like a hero yet?” asks the loading screen. Against a backdrop of a crumbling Dubai a burnt and bleeding soldier looks at something far away. His thousand-yard stare tells the player all they need to know. No. No, I don’t feel like a hero. From Darksiders to DOOM video games have put heroes in literal hell in a variety of interesting and artistic ways. But heroes don’t belong in hell not even the metaphorical kind. In its depiction of war as hell Spec Ops: The Line refuses heroes their natural place in a video game.

Six months before Spec Ops begins sandstorms bury Dubai trapping thousands of citizens, migrant workers, and the soldiers of the US Army’s 33rd Battalion behind an impenetrable storm wall. A Delta Force team consisting of Captain Martin Walker, First Lieutenant Alphonso Adams, and Staff Sergeant John Lugo is dispatched to find the source of the 33rd’s last transmission. Things are not as they seem in Dubai as the city has broken down into civil war between the so-called “Damned 33rd” led by Colonel John Konrad and the CIA-backed natives. Walker’s idealised version of Konrad sees the team take the mission further than they should leading to morally grey player choices on the way.

Walker is a good soldier and competent leader but he is no hero. There are no heroes in Spec Ops: The Line. In the early missions of the game Walker targets what he believes to be a crowd of aggressive 33rd soldiers with white phosphorous, a highly flammable kind of ordnance. Upon closer inspection Walker realises he has unintentionally burnt 47 civilians to death. The lines begin to blur and the impossible decisions, fueled by Konrad over the radio, begin to mount. Does the player kill the civilian that stole precious water or the soldier who committed murder? If the player does not choose both will die. Will the player mercy kill a traitorous CIA agent or let him burn to death? Of course, the drudgery of cover-based shooting hampers all this.

Aim. Shoot. Duck. Reload. Aim. You get the picture. Third-person-shooter games suffer from the unique affliction of being both precise and lumbering creations. Most of the time is spent watching the player character waddle around the battlefield. You can almost feel the creak of joints when the character is allowed stand up straight. Few games in this sub-genre have had any lasting impact. Remember SOCOM Navy Seals? Yeah me neither. Obviously, there are exceptions like the Gears of War series which was successful by virtue of its brutal violence, rich world, and increasingly complex characters. Where Spec Ops: The Line overcomes this hurdle is in its character design.

Walker, Adams, and Lugo begin the game as your run of the mill soldiers. Gung-ho grunts they toss jibes and insults like it’s nothing. But then darkness starts to fall. They become sunburnt, caked in sand, and suffer minor injuries. By the end of the game Lugo has broken his leg and both Walker and Adams are suffering from severe burns and trauma. Developer Yager’s decision to make the game third person made us watch these men go from Call of Duty regulars to dissociative and damaged victims. It may only be a game but the horror remains.

Smaller moments encapsulate the barbaric fiction of Spec Ops. The previously mentioned loading screens are one example. They begin with helpful gameplay tips but become progressively more sinister as the game goes on. When Walker becomes separated the loading screen announces: “When separated from your squad mates you cannot issue orders. You are all alone.” It only gets worse from there. “How many Americans have you killed today?” one asks. Others indict the player themselves. “To kill for yourself is murder. To kill for your government is heroic. To kill for entertainment is harmless.” Spec Ops asks tough questions of its players and it provides no easy answers regardless of how muddled the game gets.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” cite=”” link=”” color=”#70006C” class=”” size=”19"]Spec Ops: The Line dared to be something different among the Call of Duties, Battlefields, and other shooters out there[/[/perfectpullquote]p>

By the end of the game most of the remaining population of Dubai is dead. Thousands of people, hundreds by the players own hand, are dead and for what? The answer is nothing. Nothing worthwhile anyway. As the eternally famous line from Ron Perlman’s narration of the Fallout series goes: “War. War never changes.” That maybe true but if it is than it’s easy to see that neither do we as players. Spec Ops asks you to consider what you’re doing even as it funnels hundreds of character models made of pixels down a death tunnel full of computer generated bullets and shrapnel.

Spec Ops’ anti-war message is hard to rationalise when you play as a trained killing machine that slowly breaks down. In the game’s last chapter Captain Walker is alone. He is physically battered and his mind is coming to pieces. He is a dissociative and PTSD-afflicted wreck of a man. A husk of the competent if bland leader we see at the beginning. John Konrad is revealed to be long dead from suicide making the Konrad that Walker hears and sees a hallucination. His poor decisions are a result of a mental break after the white phosphorous incident. Spec Ops’ ending is a disaster that makes no sense and that’s as it should be. As much as it fumbles its messages about killing and war it sticks to its guns admirably.

Spec Ops: The Line dared to be something different among the Call of Duties, Battlefields, and other shooters out there. As such it was guaranteed to fail. If its occasionally clunky gameplay wasn’t off-putting than its story certainly was. As much as I admire Spec Ops for what it did within its genre it went far too deep into its darkness than any gamer was ready for in 2012. With multiple references to Apocalypse Now, Generation Kill and real-life war crimes Spec Ops wears its influences on its sleeve. If nothing else the game went to its grave whispering “The horror, the horror…” and it should be praised for such an unflinching depiction of war and the ills that come with it.