Call of Duty, White Phosphorous and Weaponising How We Play

White phosphorous burns at 2,760 degrees Celsius. That’s 5,000 degrees Fahrenheit, hot enough to melt titanium. Imagine then what it does to flesh and bone. Unsurprisingly it’s been illegally used as a weapon against civilians in Afghanistan, Iraq, Yemen and the Gaza Strip. Later this year white phosphorous rockets will appear as a kill streak reward in the multiplayer of Call of Duty: Modern Warfare. Of course the Call of Duty series has included controversial elements before from the mass killing of innocent civilians to the use of nuclear bombs but what’s especially messed up this time is that this new Call of Duty, a re-imagining of 2007’s Modern Warfare, is claiming to be anti-war.

The relationship between war and games is, to be blunt, fucked up. For decades now series like Call of Duty or Battlefield or SOCOM: Navy Seals have trained us, as gamers, to think of war as fun. War is play to a lot of gamers. It’s jumping online with your friends for three hours of mass slaughter dressed up as tactical combat. It’s idolising the butchers in the US military as paragons of bravery and virtue. It’s shooting 500 people in multiplayer just to get a weed leaf skin for your rifle. It’s fucked up.

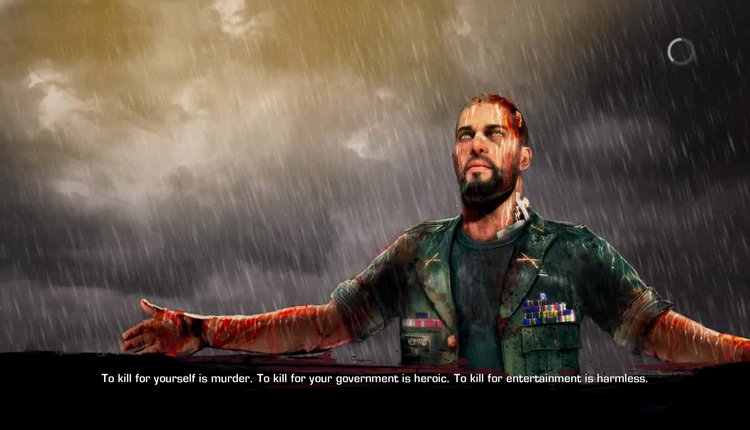

Very few games have sought to depict the harrowing physical and mental effects of warfare on soldiers and, more importantly, on civilians. Spec Ops: The Line and This War of Mine are pretty much the only two vaguely mainstream games that tried to depict war as a depraved by-product and tool of man’s greed. This War of Mine had you survive as a group of civilians in a Siege of Sarajevo-like situation. Spec Ops: The Line had you play as Captain Walker, a soldier suffering from acute mental collapse after firing white phosphorous mortar rounds on and killing 48 civilians.

Admittedly Spec Ops: The Line is a shooter concerned as much with the feel and effects of its in-game weaponry as it is for Walker’s descent into madness but it tries very hard with its primary message. Call of Duty, by comparison, has never tried very hard at all with any of its messages. The best thing that can be said about some Call of Duty games, such as World at War, is that they knew that Nazis were bad. The worst thing that can be said about some of them, such as Modern Warfare 2, is that they treated innocent human lives as playthings. It was really the Modern Warfare trilogy as well as the ongoing Black Ops sub-series that tried to imagine a past, present and future where the tools of the imperialist war machine were somehow the good guys.

Cognitive dissonance, as explained in one of Spec Ops’ infamous loading screens, is the stress that comes with holding two contradictory ideas or beliefs. The new Call of Duty: Modern Warfare, due out this October, claims to be anti-war in it’s single player story and yet in every other aspect of its single and multi-player modes it is obsessed with the weapons and tools of war along with the death and the destruction they cause. Were the latest Call of Duty capable of cognitive thought it would suffer from cognitive dissonance. A game that claims to be anti-war cannot, in all good conscience, revel in the bloody, fiery effects of war. War should not be fun in a game that claims to be anti-war.

That doesn’t mean games that feature war as a gameplay or story setting should not be fun. I’ve poured hundreds of hours into various Call of Duty games as well as Battlefield 1. Their stories might not be especially interesting but they feel damn good to play. The Witcher 3, Assassin’s Creed Odyssey and Skyrim all take place against the backdrop of devastating wars and even let you affect and change their course and they remain 3 of the best action-RPGs I’ve played this decade. War can be fun and that statement says a whole lot about how games have taught us to view war and how to play at war.

The thing with Call of Duty and to a lesser degree the Battlefield series is that they are not, I don’t think, made in good conscience. Whether the developers at the likes of Infinity Ward, Treyarch or DICE are conscious of this or not I think it’s pretty clear that the games they make profit off of two things.

One: The need by a great many people to experience the world’s greatest, bloodiest conflicts as closely as possible.

Two: The need of some of the world’s greatest superpowers to strip the earth of its natural resources and keep its working class populations subservient to its corporate and political masters.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”#70006C” class=”” size=”19"]”A game that claims to be anti-war cannot, in all good conscience, revel in the bloody, fiery effects of war”.[/[/perfectpullquote]p>

We tend to think of war as a heroic stand-off between good and evil but that was really only World War 2. Most other wars were desperate grabs at land by greedy men in wigs and suits. Men whose reach often exceeded their grasp. War has always been about capital. Capital gain versus capital cost.

The need for oil, for coal, for gold and for slaves. So it fits that games that feature war – especially Call of Duty – would be seen in that conflict over capital. You need to spend money on games about war in order to make money off of games about war. If it happens that millions of people get to experience the Battle of Berlin in as visceral a way as possible then hey great!

The problems reach far deeper than that of course. Games are effective marketing tools. It stands to reason then that the Call of Duty: Modern Warfare trilogy was probably a pretty effective marketing tool for the US and British armed forces. The characters were often members of the Marine or Ranger Corps as well as the S.A.S. Remember Gaz or Ghost? Slick fuckers with those skull masks. Elsewhere a former writer on the Call of Duty series has advised the US government on war recruitment while weapons companies from Heckler & Koch to Lockheed Martin have paid and been paid for their weapons to be realistically animated into Call of Duty games in loving detail. The situation is, in military speak, FUBAR.

It’s only when you think about it, just a little bit, that Call of Duty’s relationship with the military industrial complex becomes clear. But Call of Duty is not a game that’s meant to be thought about outside of weapon damage and bullet drop rates. It’s a switch-the-brain-off game built and designed entirely around muscle memory. It lacks any overtly obvious political allegiance other than a fetish for military men and the weapons they wield alongside a hard-on for killing men of vaguely Eastern-European or Middle-Eastern origin. But for anyone with a basic knowledge of the US and UK’s relationship with these regions it’s pretty clear cut once you stop and think. But who wants to think when fighting a pixelated war of 6 v 6 feels this good? That, for all that’s wrong with it, is unfortunately pretty hard to argue with if not against.