Interview | Writer-Director Trish McAdam Discusses Her Season at the IFI

One of the first female Irish directors to make movies about women’s lives, Trish McAdam’s innovative, always contemporary filmography is set to be celebrated with a season at the Irish Film Institute (IFI). As part of this, her latest work, Confinement – which played to a packed house at DIFF this year – will be screened. Despite McAdam’s success, however, she still finds it challenging getting a movie made.

“It’s extraordinarily difficult. The competition is huge. It’s an industry the middle has fallen out of. If you have a very big budget film or a very low budget film, it’s easy to get it off the ground. Somewhere in between, that amount of money is difficult for producers to put together,” says McAdam.

“There’s lots of hurdles you must get over. You have to convince so many people to choose your film over another. One of the reasons I make movies like Confinement is that they are reminders you can work on a tiny budget. They give you the opportunity to be creative with limitations.”

Confinement

Her latest film is an experimental but gripping piece of work. In just 34 minutes, McAdam recounts to viewers the evolution of Dublin from the early 1700s to the present day. The ghost of her old friend and dancer Tony Rudenko (voiced by a terrifically droll Aidan Gillen) narrates, touching upon some of the city’s sins.

Under British rule, the Criminal Lunatic Act of 1838 was introduced, allowing people of ‘deranged mind’ to be detained on intention to commit a crime and removed to a lunatic asylum. Even after Ireland achieved independence though, the numbers of patients in Dublin’s hospital for psychiatric treatment – Richmond Asylum (later Grangegorman) – rose 33 per cent.

As Gillen’s Rudenko says in the documentary, “the unwanted, old and disabled or the just difficult who might tarnish the family or national reputation” were treated with now out-dated methods such as lobotomies and electric shock therapy. McAdam remembers: “In the 1970s and 80s you had this knowledgable fear that if you stepped out of line a psychiatric hospital was a possible end result. It was like a threat.”

“Confinement deliberately invites the audience to excuse themselves with cliches but then turns on them. British rule wasn’t a good enough excuse in the 1970s for what was happening. We blame psychiatry and we blame the law for how they treat those with mental health issues. The truth is it’s society that’s rejecting these people, pushing them to others to deal with it. We are all culpable.”

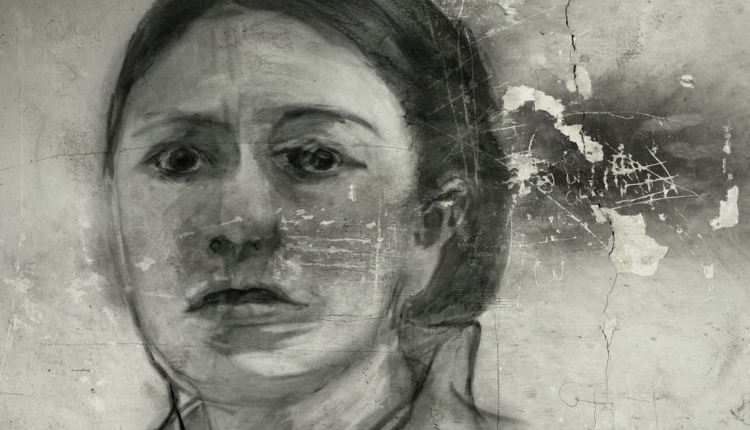

McAdam states she hopes Confinement makes viewers empathise with these ‘forgotten people’. Throughout the film, we see charcoal drawings of the faces of real patients taken from rare pre-1900 photographs.

“I went to the HSE and learned there were pictures of people admitted to the Grangegorman Asylum. These were very difficult to even get to see,” recalls McAdam. “But I showed the HSE some other drawings I did, and said I would like to draw them. I think that helped me break the taboo of them being seen in public. There’s still an element of shame associated with mental health issues.”

Strangers of Kindness

In order to depict Dublin’s evolution in Confinement, McAdam employs motion graphics to create a timespace map – one which we see change and grow over time. This is not the first time the writer-director has used technology like this. McAdam’s 2015 playful animated short film Strangers of Kindness revisits a past experience through Google Maps. While staying in Minneapolis in the 80s, the writer-director got into a precarious situation after entering into a car with a mysterious man who took her to an unusual location.

“It was really spooky looking at where I went all these years later on new technology that wasn’t invented at the time,” says McAdam. “On Google Maps you can go down to ground level. It’s a weird experience because you sometimes have to force the technology beyond where it wants to go. Occasionally it doesn’t want to go down certain routes. You have to go through bits of graphics to get where you want to. I really like the look of that – the distress of it.”

Luckily the situation with the stranger resolved itself peacefully. Speaking about what inspired her to depict in film the personal story, McAdam says: “When I tell people it, everyone tells me a tale back. It’s like a rite of passage to do something stupid like getting into a car with someone you shouldn’t.”

“I wanted to write a Me Too story, one about the negotiation that goes on between men and women. The experience didn’t stop me taking risks. I’m a risk taker in life. I always end up in these mad situations.”

Early Work

McAdam was inspired to become a filmmaker by her time living in New York. “In 79/80, I was in the East Village. There was a lot of artists holding a mirror up to their own environment. They would have exhibitions in their own apartments. I thought this was brilliant. I hadn’t been making films but it gave me the inspiration that I could based on just what was happening around me.”

Much of McAdam’s work – including her documentary What Am I Doing Here? (2008) about playwright Donal O’Kelly, her shorts about Chinese married couple Liu Xiaobo (2013) and Liu Xia (2015) and her feature debut Snakes and Ladders (1996) – centres on artists. While her first full-length movie was set in Ireland (starring the late Sean Hughes), she struggled to get it made in the country.

“I tried to get Snakes and Ladders off the ground in Ireland for a long time and couldn’t. It was only when I went to Berlin for six months and met producer Chris Sievernich (Paris, Texas) that it got made. It might feel very Irish but it’s shot in Dublin and Berlin and has international funding and an international crew.”

Following Snakes and Ladders, McAdam directed acclaimed three-part series Hoodwinked for RTE, focusing on women in Ireland since 1922. Following this, however, her output became more infrequent.

“After Hoodwinked, I got the rights to a book called The Crock of Gold by James Stephens. I wrote a script and the Irish Film Board developed it with me. It was very well received. Jim Sheridan was executive producer. David Collins was producing it. Neil Jordan was helping out. Johnny Depp had read it. It was on its way to being a feature. I don’t know how these things collapse but they can. That took about eight years. By the time I decided I couldn’t keep paying the rights for the book, I realised I hadn’t made anything in that period.”

Despite these struggles, McAdam loves the work. “People should only be filmmakers if they have a certain personality. I’ve had to do jobs in between movies – cleaning jobs, office jobs, teaching jobs. That’s stressful for me – the 9 to 5. It becomes very confined. I don’t find it stressful being a filmmaker. I love it.”

The End of Romance

Right now, the writer-director is working hard to get her passion project made. Entitled The End of Romance, it tells the story of WB Yeats’ relationship with Maud Gonne and her daughter, Iseult. “I have a great cast. The Irish Film Board are behind it. It was going to be made in 2017 and the finance fell out of place. What were trying to do is patch that back together again. I’m very hopeful.”

“I think it fits very much with the rest of my work. Yeats proposed to both Maud Gonne and her daughter. There’s that central female relationship – the dominant, political strong mother and the somewhat distressed younger daughter whose life has been destroyed by the World War I. I feel I’m the right person to make it and I’m ready.”

“In What Am I Doing Here?, Donal O’Kelly is elated after months of set-backs when his play Vive La sells out five nights. McAdam says she feels similarly on the eve of her IFI season. “It’s pleasing to see all you have done as a body of work, after constantly working on small films and trying to find places for them at festivals. When you put them together, they say more. That the Irish Film Institute would do this and that people would go to see them makes me very happy.”