Literature on Film | Part 9 | Peter Weir’s Master and Commander is an Authentic View of Patrick O’Brian’s Epic Seafaring Series

Australian director Peter Weir’s 2003 film Master & Commander: The Far Side of the World is noteworthy for being remarkably faithless to the letter of the novel on which it is based, The Far Side of the World, and yet admirably faithful to the spirit of the Aubrey/Maturin series of which that novel is the tenth instalment.

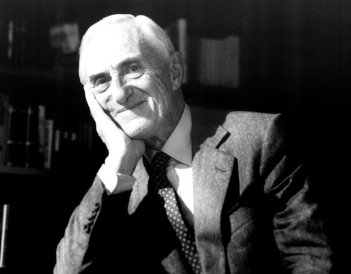

Author Patrick O’Brian was 55 when he created the characters for which he will be remembered: Captain ‘Lucky’ Jack Aubrey and Dr Stephen Maturin. To give O’Brian’s description of the pair’s friendship in The Far Side of the World, “although they were as unlike in nationality, education, religion, appearance and habit of mind as two men could well be, they were wholly at one when it came to improvising, working up variations on a theme, handing them to and fro’, on violin and ’cello.” Jack the gifted navigator and naval warrior is hopelessly naïve on land and permanently indebted, while Stephen the physician and natural scientist fluent in several languages, is a lubber at sea capable of falling between any two vessels. Yet their friendship, which begins badly with them edging towards a duel as they argue at a concert on their first meeting, is the prime mover of a saga of some twenty completed novels.

Weir and co-screenwriter John Collee bring this friendship to life by devising a largely original screen story focusing on Jack and Stephen. This is hardly surprising as The Far Side of the World, like every other entry in the series, is a picaresque affair. To be sure Jack is entrusted with a mission, but O’Brian was not one for driving plots. Weir, however, does take a number of elements directly from this book for the screenplay. The ineffectual officer Hollom is regarded as a Jonah, and the seaman Nagel does fail to make his duty to him, suffering two dozen lashes for his pains, but in the novel Hollom is having an affair with the gunner’s wife, and it is this which leads to his untimely end rather than suicide as a result of the pressure of the sailors’ superstition that he has cursed the ship. This is part and parcel of Weir’s decision to remove women from his movie to focus on the dynamics of the man of war as its own world, whereas in the book Jack lovingly writes his serial letter to wife Sophie, while Stephen agonises over an estrangement from his wife, the tigerish Diana Villiers.

Weir cherry-picks individual characters, like Mr Allen, the master, and Padeen, Stephen’s servant, who are both introduced in this novel, while dispensing with O’Brian’s introduction of members of the crew of the mutinous HMS Defender, who wreak havoc with HMS Surprise’s morale as Jack tries to integrate them. This is the subtext to the whipping of Nagel, which as a result seems far more par for the course in the movie, whereas Jack remarks to Stephen in the novel how he hates ordering lashing nearly as much as Stephen abhors the entire institution. Even more interesting is how he takes almost random moments from the novel and weaves them together consequentially for his screen story. Jack is squeamish about blood and operations, Stephen trepans a sailor’s skull while the ghoulish crew watch, Howard the marine shoots at many creatures, the surgeon’s mate Higgins is very uncomfortable with anything more advanced than teeth-pulling, a seaman falls overboard during a bad storm, there is an arm amputation, the weather turns when the true Jonah kills himself, pudding is served in the shape of the Galapagos, Jack and Stephen do have a furious row over not stopping at the Galapagos, Maturin, Padeen and young midshipman Calamy are rushed away from natural history business when a ship is spotted, Stephen does come a cropper when rushing around the ship to see a bird, and Jack does moor the ship and go ashore to save Stephen’s life: but none of these events in the novel have the weight that Weir gives them by stringing them together as a proper plot.

It is hard not to watch Weir’s film and be struck by how he is picking lines of dialogue and character moments from disparate books all across the series: one deleted scene alludes to the future laudanum addiction of a supporting character. One of the subtlest joys of the movie is the depiction of Jack dining with his officers, only on repeat viewings do you note definitively that all concerned are never entirely sober in any of these scenes; a consequence of the endless series of ‘A glass with you, sir’ toasts O’Brian presents. And so is presented in the best context the infamous weevil joke, “Do you not know that in the service, you must always choose the lesser of two weevils?” This is word for word as O’Brian wrote it, and Weir has Stephen riposte it with a quote from a different book – “He would that make a pun would pick a pocket.” Stephen critiques Jack’s corny wit in The Far Side of the World, with a quote applicable to all the officers across all the books, “Shakespeare’s clowns make quips of that bludgeoning, knock-me-down nature. You have only to add marry, come up, or go to.” And yet the humour of the books is based on solid research. Some of the peevish admirals Jack encounters in the novels recall Lord Chancellor Thurlow’s outburst at a deputation of Nonconformists, recorded in TH White’s The Age of Scandal, “I’m against you, by God. I am for the Established Church, damme! Not that I have any more regard for the Established Church than for any other Church, but because it is established. And if you can get your damned religion established, I’ll be for that too!“

“He will continue to respect historical accuracy and speak of the Royal Navy as it was, making use of contemporary documents” promised author Patrick O’Brian in his introduction to The Far Side of the World. And indeed not many pages pass before a reference is made to the late 18th century concept of ‘bottom’; which TH White defines as not just a precursor of the modern concept of ‘guts’, but also a marker of financial resources and emotional stoicism. But it is in rendering dialogue accurately that O’Brian is a marvel, men of the Napoleonic Wars speak as they would have done, of the things they would have spoken of, and with the gradations of class that would have inflected their dialect; so that when O’Brian describes the intake of the Defenders to the Surprise, the narration becomes coloured by the slang and sentence structure of the able seamen, “A few were striped Guernsey-frocked tarpaulin-hatted kinky-faced red-throated long-swinging-pigtailed men-of-war’s men, and judging by their answers as they were entered in the ship’s books some of these were right sea-lawyers too.” By hewing so closely to O’Brian’s dialogue, Weir adds usual authenticity to a Hollywood historical action adventure, from the cries of ‘Huzzay’ to Jack’s ‘Thankee, Killick’ to his servant.

It is time to talk of Killick. If the unlikely friendship of Jack and Stephen, developed over twenty novels, represents one of the finest achievements in recent literature, then the pairing of Jack and Killick must take its place among the list of masters who are positively tyrannised by their servants. “‘Put it on, sir,’ cried Killick angrily, hurrying after him and holding out a watchcoat with a hood, a Magellan jacket. ‘Put it on. Which I run it up a-purpose, ain’t I? Labouring all the bleeding night, stitch, stitch, snip, snip,’ – this in a discontented mutter. ‘Thankee Killick,’ said Jack absently, drawing the hood over his bare head” is one of Killick’s more dutiful moments in the novel, earlier he has been quite obviously ignoring Jack’s calls for dinner while he finishes an involved anecdote to a mate, before bursting in next door to attend to Jack as if he had run across the ship. Shameless star David Threlfall’s delivery of “Which it will be ready when it’s ready” while cooking in the film comes as close as bedamned to literalising this farcical relationship; if anyone else treated Jack the way Killick does they’d be hung from the yardarm.

To talk of Killick is to talk of nonsense. And to talk of nonsense in O’Brian is to note its almost total absence in Weir’s adaptation. Conventional wisdom has it that cinema audiences are unwilling to tolerate nonsense. So Marvel movies hold back from the madness of Mark Millar’s The Ultimates, while Vin Diesel drives cars through multiple skyscrapers yet keeps his audience onboard. Master & Commander: The Far Side of the World was always going to be a horrifically expensive undertaking given Weir’s commitment to authenticity, shooting on a Nelsonian replica ship in the tank that housed Titanic’s production, and using extensive CGI to add to the impact of storm sequences as HMS Surprise rounds the Cape. And so the utter nonsense that fills the novel got discarded; no skit on the King James Bible involving Admiral Ives causing hilarity in the fleet at Gibraltar, no unfortunate attempts at Shakespearean quotation by Jack forgetful that he was shipping not only able seaman Macbeth but also able seaman Macduff, no mention of how Barker of the Iris was attempting to get sailors whose surnames were colours to man his barge and dress in appropriate livery because he’d been told Iris meant rainbow in Greek, and above all no possibility of Jack and Stephen falling out the stern window of the Surprise while attempting to net fish and the absence of the ship’s captain and doctor not being noticed for many a long hour. And that mind is just the tenth novel in the series, throughout the series there are an endless series of farcical scenes including Jack pretending to be a dancing bear in France, and Stephen’s sloth eating Jack’s gold epaulettes in a provoking manner despite Jack’s entreaties (“Give it up sir! Give it up directly, d’you hear?!”).

To talk of Killick is to talk of nonsense. And to talk of nonsense in O’Brian is to note its almost total absence in Weir’s adaptation. Conventional wisdom has it that cinema audiences are unwilling to tolerate nonsense. So Marvel movies hold back from the madness of Mark Millar’s The Ultimates, while Vin Diesel drives cars through multiple skyscrapers yet keeps his audience onboard. Master & Commander: The Far Side of the World was always going to be a horrifically expensive undertaking given Weir’s commitment to authenticity, shooting on a Nelsonian replica ship in the tank that housed Titanic’s production, and using extensive CGI to add to the impact of storm sequences as HMS Surprise rounds the Cape. And so the utter nonsense that fills the novel got discarded; no skit on the King James Bible involving Admiral Ives causing hilarity in the fleet at Gibraltar, no unfortunate attempts at Shakespearean quotation by Jack forgetful that he was shipping not only able seaman Macbeth but also able seaman Macduff, no mention of how Barker of the Iris was attempting to get sailors whose surnames were colours to man his barge and dress in appropriate livery because he’d been told Iris meant rainbow in Greek, and above all no possibility of Jack and Stephen falling out the stern window of the Surprise while attempting to net fish and the absence of the ship’s captain and doctor not being noticed for many a long hour. And that mind is just the tenth novel in the series, throughout the series there are an endless series of farcical scenes including Jack pretending to be a dancing bear in France, and Stephen’s sloth eating Jack’s gold epaulettes in a provoking manner despite Jack’s entreaties (“Give it up sir! Give it up directly, d’you hear?!”).

The other glaring shortcoming is Stephen’s full character. Russell Crowe and Paul Bettany give note-perfect renditions of Jack and Stephen, but Bettany is playing only half the scale O’Brian gives Stephen. The Irish sentence structure that occasionally sneaks into Stephen’s dialogue, “Are we ever going to play our music now? It is the busy day I have tomorrow”, is banished from the film, as is Padeen’s conversing with Stephen entirely as Gaeilge; Padeen being from Clare, and his monoglot status and cleft palate the reason for his detention in a lunatic asylum until pressed into the Surprise. Jack and Maturin become firm friends even amid the tension caused by the presence in the first novel of Lieutenant James Dillon, a former colleague of Stephen in the United Irishmen, a past both must keep secret from the Jack whose speech on Nelson in the first book Weir could not pass up: ““someone had offered him a boat-cloak on a cold night and he had said no, he was quite warm – his zeal for his King and country kept him warm. It sounds absurd, as I tell it, does it not? …but with him you feel your bosom glow.” The exchange about informers and republicanism “Now you’re talking like an Irishman” “Well, I am an Irishman” is thus comic in the film, but by eliding Stephen’s heritage, and his role as a naval intelligence agent, the friendship with consummate Tory Jack is made perhaps less remarkable than it is.

But such are the choices of adaptation. Not everything can survive. Indeed Peter Weir in a DVD extra states that adaptation involves shaking a book so that its beautiful prose falls out and is replaced by equivalent visual metaphors. And when you see this passage, “With the idlers called and both watches on deck he packed them along the weather rail to make her stiffer still, set his mainroyal and stood there, braced against the sloop of the deck, soaked with flying spray, looking perfectly delighted”, rendered as a push-in over the water panning along the edge of the Surprise as it races along with the crew all hanging off the edge of their ship and damn near with their handkerchiefs out to get every last bit of good from the wind, you appreciate what Weir has achieved. Weir unusually used multiple cameras for action sequences providing him with choices galore in the editing bay. And while he whipped his cast into such a state of preparedness that they could probably have sailed a tall ship for real, he did not let this attention to historical detail get in the way of the action. Yes, when James D’Arcy stands on the quarterdeck as Lt. Pullings he is standing in the right place, but more importantly we care about Pullings as a character. Weir’s fidelity to O’Brian is absolute, though there be digressions in the film into Stephen anticipating Darwin with a discovery on the Galapagos, the tragedy of a Jonah tearing apart ship’s morale, and Jack displaying distinctly tyrannical qualities in his hunt for the phantom French ship Acheron, the true course is always attained – that of rip-roaring adventure.