Literature on Film | Part 5 | Be It the Book or Film, Into The Wild is the Story of Living

“No man ever followed his genius till it misled him” – Henry David Thoreau (Walden or Life in the Woods)

Have you ever seen the film Into the Wild? If not then I implore you to do so; it is a beautifully crafted film and a celebration of not only life but of the joy that can be found in travel, exploration and (self) discovery. Have you ever read the book it is based upon, also called Into the Wild? If not then I implore you to do so; it is a painstakingly researched investigation into the life and tragic death of a young man whose disenchantment with society and all its trappings drove him to try find the joy in living he so jealously craved. Both film and book are concerned with the final years of Christopher Johnson McCandless, a person known more so by his tragic death at twenty-four as for his attempts at shedding the shackles of ownership, possession and career that he found so overwhelmingly stifling. Yet watching the film, directed by Sean Penn, and reading the book, written by Jon Krakauer are very different experiences. Based on fact, it is not their subject matter that is dissimilar; what sets them apart is the manner of their telling and it is this very reason why both Penn’s film and Krakauer’s book are so uplifting and distressing and absorbing, but not in equal measure.

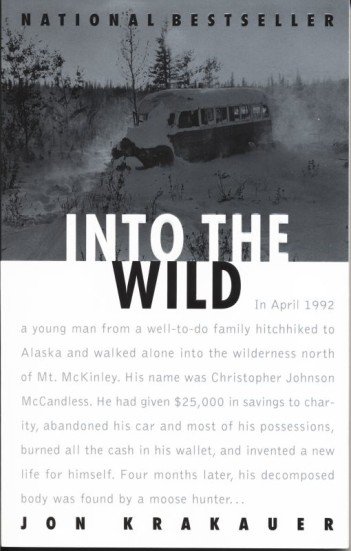

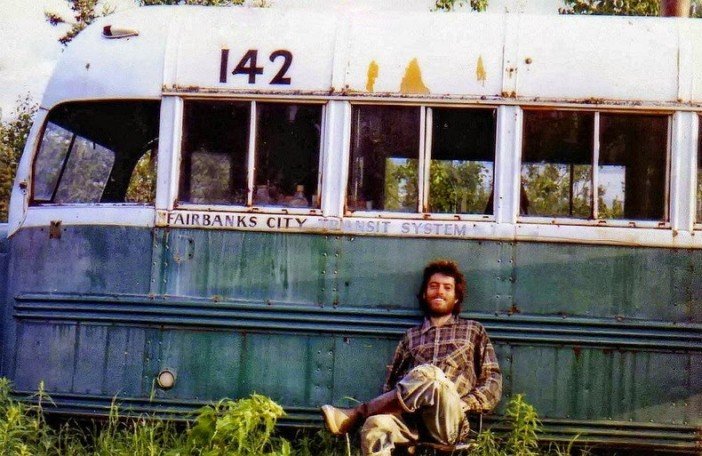

Krakauer’s book, a bestseller when published in 1996, was inspired by an article he wrote in 1993 for Outside Magazine about a young man, Christopher McCandless (otherwise known to everyone he met on the road as Alexander Supertramp), who in 1990 hiked across America for close to two years before trekking into the Alaskan wilderness. In August of 1992 his body was found in the rusting hulk of an abandoned Fairbanks City bus just off the Alaskan Stampede trail. Krakauer found himself drawn to McCandless and to his Alaskan story, as it could so very well have been his own. A dedicated mountain climber, Krakauer makes a little elbow room for himself in Into the Wild, shoe-horning an account of his own solo ascent of Alaska’s notorious mountain, The Devil’s Thumb. This is not an exercise in navel gazing, he uses his own personal experience here as a conduit for understanding and meaning, juxtaposing his own life against that of McCandless’. When news broke in the August of 1992 that McCandless had died, the initial reaction by many was complete puzzlement – no one really understood who McCandless was, what he aspired to be or how his actions could have lead to anything other than a premature death. Krakauer was not one of those people; he identified very clearly with McCandless as he ventured into the Alaskan wilds as a young man and very nearly did not return himself. Here lies the first major narrative difference between book and film, Krakauer’s own inclusions in the book is something that Sean Penn’s film makes no reference to. There is one main reason for this, where Krakauer’s book sought to explain the events of McCandless’ journey that lead to his death, Penn simply wishes to celebrate (and maybe someway romanticise) the journey that McCandless took and all the wonderful things he saw and experienced. Like Dickens in the opening lines of A Christmas Carol, the viewer/reader must understand this fundamental difference or nothing that follows in either book or film will seem wondrous.

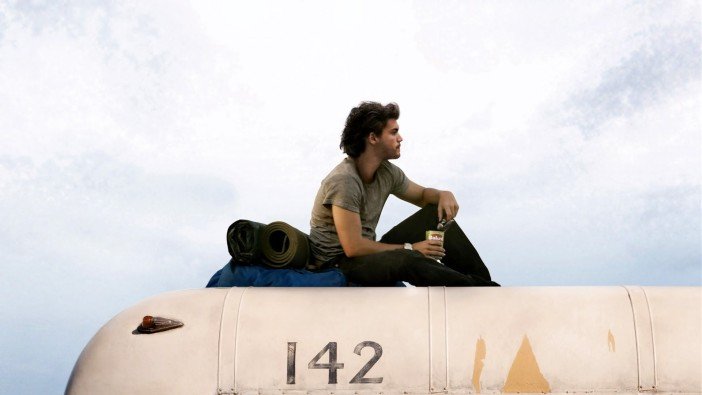

Who was Christopher Johnson McCandless? If you want to know that then you will have to read the book as Sean Penn’s film only covers the last two years of his life whereas Krakauer delves into his past to form a more rounded notion of the boy who became the man. Penn’s film presents McCandless as an idealistic dreamer, a young man rebelling against the system and authority, like all teenagers invariably do at some point. He crafts a man seeking truth, seeking honesty, who wishes to burst the bonds of society and all that is expected of middle class American suburbia – he doesn’t want a career, a new car, a large house and all that goes with it. He wants the joy of new experiences, the pursuit of truth; he wants the open road and a wealth of possibilities – you can almost feel the travelling itch that McCandless found impossible to repress in the opening 20 minutes of Penn’s film. Penn’s McCandless is someone easy to admire and easy to love. Krakauer’s account of McCandless is much different. McCandless, from an early age, raged against rules and fostered an antagonistic relationship with his parents, something that grew from adolescent embarrassment to virtual hatred as he graduated from college. The deep resentment he felt for his parents and their ideals (the American Dream) is surmised, in both Krakauer’s book and Sean Penn’s film, as the catalyst for McCandless’ odyssey across America. He wished to divorce himself from his family, but he didn’t want to just terminate a relationship, he wished to cause them pain; Krakauer’s Chris is, in places, quite unpalatable and almost completely at odds with the character that Sean Penn creates. In the film he is a bright, optimistic dreamer, care free and full of energy and enthusiasm for new experiences. In the book he is far more complex, far more emotionally agitated and in some ways cruel.

In Krakauer’s book, Chris explains to his younger sister, Carine, prior to his disappearance, what he intends to do,

“…for a few months after graduation I’m going to let them think they are right, I’m going to let them think that I’m ‘coming around to their side of things’ and that our relationship is stabilising. And then, once the time is right, with one abrupt, swift action I’m going to knock them out of my life…I’ll be through with them once and for all, forever.”

These are not the words of a young man who simply wished to unyoke himself from the dreams and expectation of his parents. He wished to inflict upon them emotional damage. These are also thoughts that would not make an audience sympathetic for a character’s plight so Penn jettisoned the deep anger and borderline hatred Chris felt for his parents. He moulded McCandless into a character that was far easier to digest and, possibly more importantly, feel great sympathy for. Penn does not shy away from the turmoil in the McCandless family, the threats of divorce and the sense that Chris’s parents never really understood him; he just doesn’t give much time to developing the strained family dynamic. Yet, as mentioned above, Penn’s film is not about why, it is not about explaining circumstances; his film is a celebration of life and one life in particular that ends in tragic circumstances. He didn’t want his audience feeling a sense of ambivalence towards its ending or central character, he needed the audience to love Chris. Krakauer did not feel this need, he presented Chris as remembered by friends, by his parents and sister and by those he met along the road and he allowed the reader the space to make up their own minds. Where Penn builds a character for the viewer, Krakauer allows his readers to build one themselves.

As mentioned earlier, Sean Penn’s film is a celebration of Chris’s life but it does not ignore the path he took which led eventually to his death. The common theory behind his death, shared by both book and film, is that McCandless ate, for a considerable period of time, a toxic plant mistakenly thinking it was edible and non-poisonous. This theory is based on diary entries that McCandless himself made, which suggests the root cause of his death was simply ignorance of the environment he was in. In the book (and in subsequent articles in Outside Magazine and the New Yorker) Krakauer voices opinions of those who believed that McCandless’ trek into Alaska was some sort of drawn out suicide bid. This is based on the opinion that if you intentionally spend a prolonged period of time in any place as unforgiving as Alaska without proper supplies, preparation and knowledge (McCandless was not an outdoorsman or a hunter, he didn’t own wet gear or Wellington boots before starting through the snow and did not even carry a map of the area before he set out on his adventure) then you cannot possibly expect to survive. Sean Penn’s film does not even touch on these thoughts; his film intimates that McCandless’ death was a tragic accident brought about by circumstance and ill luck – the film does not entertain the notion that Chris McCandless wanted to die. Krakauer’s final thesis also dismisses the idea that Chris committed suicide, but he does give breathing room to those who felt Chris did. In Penn’s film there is too much joy to even contemplate that Chris McCandless harboured any dark intention to end his life through reckless abandon. In a diary entry Chris made less that 6 months before he died he wrote,

“…the experiences, the memories, the great triumphant joy of living to the fullest extent in which real meaning is found. God it’s great to be alive. Thank you. Thank you.”

These few words almost perfectly encapsulate the Chris McCandless that Sean Penn brought to the screen and his maxim is itself echoed by the words of Chris’s parents; on a plaque located where his body was found, they wrote, “Chris, our beloved son and brother, died here during his adventurous travels in search of how he could best realize God’s great gift of life.” Throughout the film this is repeated and expounded, be that through the numerous friendships he forged or the wonderful things he saw. Penn hammers home the belief that Chris never intended to walk into the wild to never walk back out again.

Krakauer also believes that Chris never intended Alaska to be his end game, but he is able to draw on something that Penn does not and cannot – experience. In explaining McCandless’ motivations, he introduces the story behind his own Alaskan adventure. At twenty-three (one year younger than McCandless when he died), Krakauer was filled with a cock-sure, folliless sense of self-confidence necessary for anyone to achieve any burning ambition deemed by society, or commonsense, as lunacy. At this age he made an attempt on the then unclimbed southern face of the Devil’s Thumb in Alaska, and almost died in the process. But, like McCandless, Krakauer did not journey to Alaska to die, but to live. When he first wrote of Chris in his Outside Magazine article, Krakauer found someone who he could relate to, someone who understood the irresistible lure of placing your life in your own hands and the undeniable exhilaration of living only when you are closest to the edge. Yet for Krakauer, as he assumed was also the case with McCandless, death was never really an option or a factor that may have put the brakes on his plans. Explaining it, Krakauer wrote,

“Death remained as abstract a concept as non-Euclidean geometry… I couldn’t resist stealing up to the edge of doom and peering over the brink. The hint of what was concealed in those shadows terrified me, but I caught sight of something in the glimpse, some forbidden and elemental riddle…In my case – and I believe, in the case of Chris McCandless – that was a very different thing from wanting to die.”

This desire to live is constant throughout both Krakauer’s book and Sean Penn’s adaptation. One of McCandless’ earliest diary entries, as he set out into the Alaskan wilderness, reads,

“…I will live in the wild, away from civilisation and without money. Being alone without government control and the poisonous civilisation, I can truly live as a free spirit in the ultimate freedom. I now walk into the wild.”

Another entry, several weeks later, emphasises his contentment with his situation,

“I am now living life in its most natural and purest form. God it’s great to be alive.”

These few lines are proof that McCandless intended to live and continue living in the wild and out of it (Krakauer deduces, from his various diary entries and underlined passages in his books that Chris McCandless intended leaving the wild). These lines, and many more from McCandless’ diary pepper Penn’s film, beautifully transposed over the imagery in McCandless’s own handwriting. Further evidence of Candless’s desire to live is a note posted by McCandless, as the full extent of his predicament became apparent to him, it read

“Attention possible visitors S.O.S. I need your help. I am injured. Near death and too weak to hike out of here. I am all alone. This is no joke. In the name of God, please remain to save me…”

Couple that with this, another diary entry recorded by McCandless,

“Day 69: Rained in, river looks impassible. Lonely, Scared”

and we have an image of a man who, at all costs, did not want to die, validating the opinion that Chris McCandless’ death was not a suicide.

The telling of McCandless’ story also differs from book to film. Krakauer built a heavily investigated account of McCandless’s final years around multiple perspectives; of those Chris met along the way, of newspaper clippings and family interviews. Krakauer’s story is very much an after the fact account of Chris’s life whereas Sean Penn’s film tells Chris’s story entirely through Chris’s eyes. He uses a voiceover narration from Carine, Chris’s younger sister, to stitch together the various flashbacks and narrative digressions to Chris’s parents as they fruitlessly search for him, but the overall arch of the film is told almost exclusively from Chris’s point of view. He is the storyteller. This is one of the main deviations from Krakauer’s book as there is now only one central voice. Everything we see and hear is through his eyes in the film yet in the book we see very little of what Chris sees, save moments taken from his diary entries; the Chris of the book is built by those whose lives he touched. The film presents Chris without making real reference to his past or formative years (Carine does narrate an episode of domestic abuse they witnessed as children, but only a fleeting glimpse of what they grew up through) or indeed the future, Chris is mainly an idealistic young dreamer with a whole world to see.

One of the major omissions of material from book to film is easily the most heartbreaking and it is wisely left as the sole custody of the book – how close Chris came to saving himself. When Chris decided he had spent enough time in Alaska, he packed his belonging and walked back down the Stampede Trail, the route he had taken into Alaska. Several months previous he had crossed a slow flowing knee-deep river called the Teklanika, but on his attempt to walk out of the wild Chris came across a raging torrent of water, the Teklanika swollen with meltwater and well beyond crossing by even the strongest of swimmers. Here Chris makes the mistake that eventually costs him his life – he returns to the abandoned bus he had called home for the last three months. Krakauer informs the reader that if Chris had hiked half a mile down stream he would have come across a gauging station built by the U.S. Geographical Survey, with a cable and basket suspended about 15 feet above the river designed specifically for crossing the Teklanika when it was swollen beyond crossing by foot. Chris would have survived. Krakauer also explains that if Chris had turned the opposite direction and hiked upstream the raging Teklanika soon broke down into its tributary river branches, each of which would have been easily crossable by foot. Chris would have survived. He goes further again to say that within a day or two’s hike of Chris’s abandoned Fairbanks City bus were no fewer than three cabins, each stocked with a limited amount of food and medical supplies. Chris quite possibly would have survived. Further again is the knowledge that Chris was not in the great Alaskan wilderness at all, he set up camp on the very edge of Denali National Park, approximately 20 miles from a highway patrolled by park officials. If Chris had have walked either upstream or down or explored a little further into the wilderness he quite possibly would have found his salvation. If he had possessed a map of the area (which he didn’t) each of these means of saving himself would have become apparent to him as the cabins, the gauging station and the highway were all marked. Chris’s wish to live in isolation in the wild ultimately cost him his life, but these possible saviours are not accounted for in the film, Penn makes no mention of them as in doing so would almost negate the journey that Chris was on, it would almost make his life and his death seem futile. The tragedy of Chris McCandless is not that he died lost in the wild, but that he died trying to find himself in the wild.

There are other differences between the book and the film – the story behind the Fairbanks City bus is explained in detail in the book, but not in the film. The character of Tracey, the girl he meets in Slab City, is merely glanced over in the book whereas she is a major character, a love interest, in the film. In the book his parents go to great lengths to try find him, going as far as hiring a private detective. While this is briefly mentioned in the film, no great emphasis is placed on it. The film portrays Chris as a hero, whereas in the book he is neither hero nor victim, he is merely an unfortunate casualty of circumstance. In delineating the differences between film and book, it should also be noted that there are differences between the reality and the book and the film. While Chris kept a diary on his travels, his entries while in Alaska were sparse to say the least, so Krakauer, with a great deal of guesstimating and informed research, had to draw his own conclusions as to how Chris lived day-to-day. Penn in turn built his film around Krakauer’s narrative of how McCandless survived in Alaska. For a lot of what we see in the film and read in the book there is no hard evidence that these events occurred, or at least occurred as presented. Craig Medred, a writer with the Alaska Dispatch News, has tried to highlight the factual and fictional inconsistencies with Krakauer’s book on more than one occasion. In January of 2015 he wrote,

“In writing the book, Krakauer took an individual word or two from McCandless’ journal and around such entries created little stories. Where McCandless wrote the single word “caribou” at No. 105, Krakauer reported that “On August 10, he (McCandless) saw a caribou but didn’t get a shot off.” The date is a guess based on the numbers in McCandless’ so-called journal. There is not even that thin thread to support the observation that McCandless “saw a caribou, but didn’t get a shot off.”

This type of interpretation has led Medred, among others, to question the idea that the Alaskan element of McCandless’ life was “based on a true story.” In truth Krakauer surmised a great deal of McCandless’ final months but based his final conclusions on the material he had at hand, namely McCandless’ journal, his photographs, Krakauer’s research and his own first hand experience of living in Alaska. To call Krakauer’s book a work of fiction is not only an insult to Krakauer but also to the person Chris McCandless was, or at least wished to be.

Christopher Johnson McCandless died on August 18th, 1992. The final words he wrote in his journal were as follows;

I have had a happy life and thank the Lord. Goodbye and may God bless all.

In those final days and weeks he shed his alter ego of Alexander Supertramp and signed his final passages as Christopher Johnson McCandless. Inspired by the work of Boris Pasternak, he underlined the following passage in the book Doctor Zhivago:

“Lara walked along the tracks following a path worn by pilgrims and then turned into the fields….It was dearer to her than her kin, better than a lover, wiser than a book. For a moment she rediscovered the purpose of her life. She was here on earth to grasp the meaning of its wild enchantment and to call each thing by its right name….”

In death he may finally have been happy to be who he always was – Christopher Johnson McCandless. And while we will never fully know what his ambitions were and what he hoped to achieve after Alaska, using Krakauer’s book and Sean Penn’s film we are guaranteed one thing for certain – Christopher Johnson McCandless was a man full of life, of vigor and energy. A man who lived.

Featured Image Credit Source