Literature on Film | 14 | No Country for Old Men Brings Cormac McCarthy’s Bleak Modernist Realism to Cinematic Heights

A man I know often ponders the contradiction observed in a mutual friend, a writer. “Why does she write such sad books, and yet have such twinkly eyes?” he laments.

The author in question certainly does write very serious fiction. It’s grown-up material, beautifully constructed, and not without flashes of wit; but the basic theme is that life sucks, and sucks more as you grow older.

That may well be true, but sometimes we prefer, in the audience, to have a little light relief.

Well, you don’t get that in Cormac McCarthy novels, but you might in the films made from them. McCarthy’s novels are so unrelentingly bleak that seeing them enacted could be enough to empty the movie theatre, the distressed patrons heading like lemmings for the nearest cliff. The Road – not many laughs there; All the Pretty Horses, slash your wrists; but No Country for Old Men: sunlit, compelling, and terrifying.

Under discussion here in particular is No Country for Old Men. Winner of the Academy Award for Best Picture in 2007, it’s one of the great films of the 21st century, labelled “neo-western” or “desert noir” to give some sense of its genre-busting brilliance. At the same time, the original novel possesses the features of clean uncompromising drama – or, in a simpler description, bleak-as-fuck. It’s a gruelling if unputdownable read.

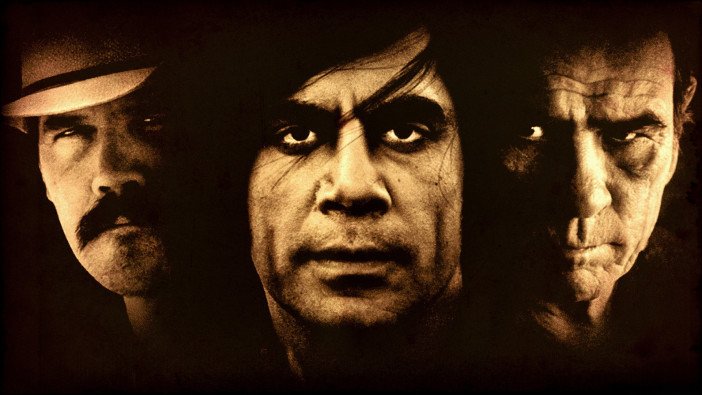

The story is set in Texas in 1980, hence featuring drug trade on a major scale because of proximity to Mexico, and the developing mega-fortunes to be made by the unscrupulous. The protagonists are an uneven trio, lawman Bell (Tommy Lee Jones in the film), poor man Moss (Josh Brolin) and nutjob Chigurh (Javier Bardem).

Moss comes across the aftermath of a violent stand-off between players in the trade, all dead – except for one poor soul who begs him for water. He belatedly responds to this request – and that seals his fate. For any readers who haven’t seen the film, that will be all the exposition here, save to say that the immediate pursuit of Moss, featuring very unfriendly dogs, will make your hair stand on end.

Meanwhile, a strapping fellow with the worst haircut since the Bee Gees is slowly and purposefully making his way around the state killing people with a bolt gun. In the book, Anton Chigurh is a bloodless, enigmatic figure. In the film he is certainly enigmatic and emotionless, but brilliantly realised, and underplayed, by an impassive Javier Bardem – this gained the actor the Best Supporting Oscar, a first for Spain.

The threads of the three men’s stories are drawn together simply and skilfully by McCarthy, a master craftsman of the everyday and the horrific combined. In the book there are regular passages which are Sheriff Bell’s internal monologue. For the film, directors the Coen brothers have eschewed the voice-over and turned these thoughts into conversations. It must have worked, for this customer, at least, as I didn’t find the sentiments expressed aloud jarring in the film. At one stage, Bell talks about an item he read in the newspaper, about a couple in California who had established a guest house for elderly people, then murdered the old people and continued to cash their social security cheques.

Bell just records this gruesome fact, as part of an account of how bad things have gotten in the world. His narrative style is laconic, low-key, the opposite of the emotional over-empathic style that is so much the fabric of modern discourse, fuelled by social media and the imperative to “share”. And in that it’s all the more attractive, especially when given voice by Tommy Lee Jones.

This is an unpretty gritty male world. Kelly McDonald’s portrayal of Moss’s wife succeeds in giving her character more heft than it has in the novel, but she is mostly incidental to the power play and pursuit involving the three main male characters. Into this mix comes Woody Harrelson, doing his shtick superbly, as hit man Wells – again, a character that is a noir delight in the movie, although somewhat a bit player in the novel.

If a choice had to be made between film and book, if you could only devote time to one, it would have to be the film. Yes, McCarthy’s dry-eyed account of evil in a down-home setting provides the material. And his oblique probing of existential questions gives the story depth. But the realisation, the cinematography, the lighting – and most of all the wonderful performances by the cast – make the film unmissable.

Quoted in The Guardian, the screenwriter of The Road, Joe Penhall, comments that the vicious, violent wider world in which we now live makes audiences more prepared to accept McCarthy’s dystopian vision:

“Post-9/11 we are frighteningly aware of what man is capable of. We’ve seen the randomness, the overheatedness, the irrationality of people’s vengefulness in Islamist terrorism, in American imperialism, in British foreign policy,” Penhall said. “People see these examples of extreme behaviour on the news every night and don’t know what to make of it, and McCarthy kind of does know what to make of it. By the time McCarthy’s stuff gets to the screen we’re not thinking, ‘What a radical, harsh vision’; we’re thinking, ‘Yep, that’s a world I recognise.‘”

Featured Image Credit