10 Years On | Is Funny Games A Soulless Exercise In Movie Violence?

*This article contains spoilers for Funny Games*

The original Funny Games debuted in 1997, generating a critical storm of both condemnation and adoration. Directed by arthouse darling Michael Haneke, the film acts as a contemplative thesis on the nature of consumable violence, particularly that which is expressed through the American slasher film. As an audience we are forced to question which strains of violence are permissible and which are simply tasteless, a challenge that proved too much for some filmgoers.

Haneke remade the film, beat for beat, with an American cast in 2007 (and released on this day in 2008). The act of remaking emphasises the director’s original critique – that through viewing the film once more we are satisfying our desire to witness repeat violence, and by transposing the setting from Austria to the United States, he brings the critique straight to the originator of cinema violence, Hollywood.

The plot of the film is thin by design. It is less concerned with narrative convention than it is by scrutinising filmic violence. Its goals are outlined clearly from the get-go. A well-to-do family venture to their lake house to vacation: Ann Farber (Naomi Watts), her husband George (Tim Roth) and their son Georgie (Devon Gearhart) travel along a tranquil country road listening to opera, and take turns guessing the composers of the tracks they are listening to. This supposed calmness is interrupted when the main titles appear, and a heavy metal song by US band Naked City plays over the dialogue, silencing the family, operatic score and the initial serenity of the scene. The comfort of the middle-class existence continues to be uprooted by the visit of two home invaders, Paul (Michael Pitt) and Peter (Brady Corbet), who torture the family with a series of sadistic games that ultimately result in their deaths.

Haneke has never shied away from class critique. In fact, it has become exemplary of his work. His 2005 psychological thriller Caché, for example, centres around the collective guilt of French colonialism and the country’s treatment of Algerians. Even his most recent film, Happy End (2017), features periphery commentary of the lived experience of immigrants in Calais. However, what these films contain, and what is missing in Funny Games, is backstory. The protagonist of Caché is punished for mistreating his adopted younger brother, an Algerian, in his youth; his experience acting as a metaphorical return of the repressed narrative for the French nation. The family in Happy End are embarrassed by a rogue contingent in their collective for ignoring the plight of migrants in France. Such narratives contain middle-to-upper class families who face their comeuppance for wilful prejudice.

Little is known about the family in Funny Games, save for that they maybe enjoy quinoa. Their characterisations are not just flat, but practically non-existent. We know that they listen to opera, own a boat, that they keep their house in pristine condition and have a fully stocked fridge, but there is no catalyst for the violence inflicted upon them. They are simply blank canvasses upon which Haneke can cast his experiment in torture porn.

The captors are not named consistently. Initially introduced as “Peter/Paul”, they refer to themselves throughout by a variety of pop culture double acts, such as “Tom/Jerry” and “Beavis/Butthead”. They also invent numerous inconsistent backstories, telling the family that they come from poverty, that they are simply bored rich kids, or that they are drug addicts who steal from wealthy families to feed their habit. Their names and backstories are not important. Much like Ann, George and Georgie, they lack traditional characterisation and act as omnipotent beings who seemingly know what is about to transpire before the audience does. They enact violence in a methodical, cool and collected way, making for some unnerving performances from Pitt and Corbet.

Despite its reputation, the film shows little explicit violence. Instead, the violence is simply implied by clever use of filmmaking techniques. When the captors force Ann to undress, Haneke does not give in to the sensationalist tendencies of Hollywood cinema, instead choosing to rest the camera on a close-up of Naomi Watts’ pained expression, and the reactions of her traumatised husband. We are therefore forced to imagine the violence in our minds, and question what it is we expected to see or, more bleakly, what some viewers might want to see.

[perfectpullquote align=”right” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”#F42A2A” class=”” size=”15"]Any indication that the family will escape their circumstances [�[…]re offered up and immediately crushed, quelled, quashed, and rejected by a film that takes every conceivable route to confuse and shock you into thought.[/[/perfectpullquote]p>

The film also contains what may be the most upsetting sequence I have seen in cinema, and again, the action immediately preceding it takes place offscreen. Broken and bound, the family are left helpless as Paul goes to the kitchen to make food. We watch him leave the room, open the fridge and proceed to make something to eat. Then, a loud bang is heard, followed by intermittent, animalistic screeching. This continues for some time as the audience is left puzzled as to what has happened.

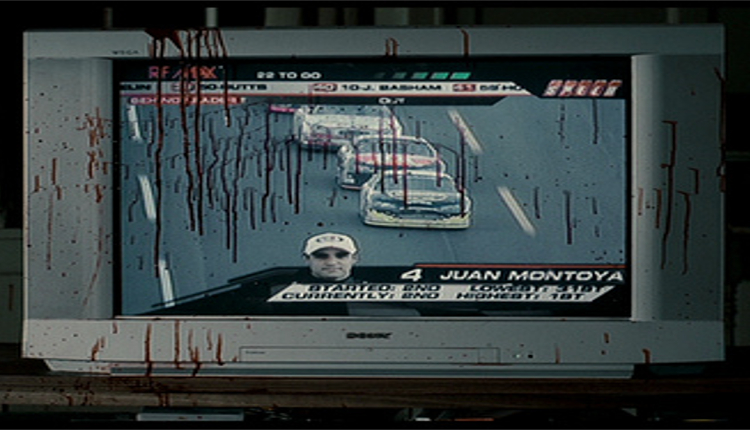

The following shot is of a blood-stained television, a staggering image that Haneke makes great pains to emphasise (because what more screams violence in American media than a bloody telly?) The invaders squabble among themselves while the film remains static on this shot, and eventually they leave. The following sequence reveals to us what has happened: Ann is seen in the background, hunched over, utterly speechless and dehumanised. In the foreground: the body of her now dead son, Georgie. He has been shot by Peter, his blood spewed over their once white walls and their television, the horror of home invasion made reality in their pristine middle-class lives.

The next ten minutes are shot as an excruciating single-take. We watch Ann struggle to get up, hobble offscreen, free herself of her bonds, and come to comfort her broken husband. The audience is made process the horror of what has happened in real time alongside the fictional family, and therefore made aware of the outcomes of the violence they so easily consume in mainstream cinema.

Throughout the piece, any indication that the family will escape their circumstances, any glimmer of hope offered to suggest we will soon follow traditional narrative standards, are offered up and immediately crushed, quelled, quashed, and rejected by a film that takes every conceivable route to confuse and shock you into thought.

Georgie’s death, for example, stems from Haneke’s rejection of narrative expectations. Prior to this we see Georgie break from his captors and escape the house. A set-up such as this conjures many suppositions: when a child breaks free in a horror or slasher film, it is expected that they are going to find help, from authorities or from a friend, á la The Shining for example. This does not happen. Georgie is found by Paul, who kidnaps him once more, takes him back, and this eventually leads to the boy’s murder.

Later, when Peter is shot by Ann, providing the audience with some much-needed catharsis following their litany of violent acts, Paul simply picks up a television remote and rewinds the scene, thereby preventing the action from having ever happened. Narrative convention is once more usurped, and we are left to question which modes of violence are acceptable (the death of an evil-doer) and which are not.

Regardless of what version you are watching, Funny Games is a painful watch, acting as a rather soulless one hour and fifty-minute essay in violence on screen and how we need to change our ways. It is one of the few films I have watched in my lifetime that actively positions itself against the viewer and takes every conceivable opportunity it can to anger you. Then again, maybe it was not supposed to be enjoyed in any conventional way, especially when taken for what it is: a filmic experiment into our enjoyment of violence and nothing more.