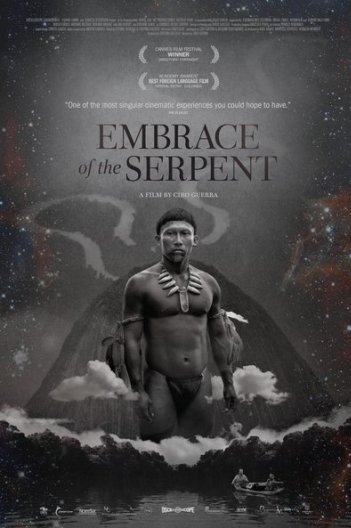

Film Review | Embrace of the Serpent is as Visually Stunning as it is Morally Important

While sitting in at the modestly attended critics screening of Ciro Guerra’s Amazonian odyssey Embrace of The Serpent, I couldn’t help but be reminded of two of cinema’s most enduring art film epics: Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now and Werner Herzog’s Aguirre, the Wrath of God. Guerra’s film, like those 70’s classics, features ‘heroes’ who make arduous, self-questioning and surreal journeys thorough the treacherous, environment of the never ending jungle river. All 3 works are of a seismic, singular ambition. What struck me, however, was not the similarities between this film and the others but rather the differences. There is no doubt that Coppola and Herzog gave us unquestionable masterworks, but in doing so they also marginalised the native people whose suffering they intended to document.

The local Vietnamese and Peruvians in those films are nothing more than sinister spear chuckers, silent slaves or easily manipulated victims, whose presence is often used to embody the menacing threat the landscape has in store for our protagonists. They are the savages on the side-lines, it is not their story. Embrace of the Serpent, Guerra’s spellbinding third feature, seeks out to upend this trend and reclaim the narrative in the name of the wrongly forgotten native populations who lived in the secluded depths of the Amazonian jungles. Like few features that I have ever seen, outside of documentaries, Embrace manages to inhibit itself in – and successfully realise – the hidden worlds that exist beyond our comprehension. Gurrea, himself a Colombian, displays a deeply profound sense of empathy that permeates every frame, line of dialogue and facial expression.

The binary plot of Embrace is a very, very loose adaptation of the diaries of two real life adventurer scientists of the early 20th century. Following German ethnologist Thomas Koch-Grunberg in 1909 and American botanist Richard Evan Schulte’s in 1940, the decades spanning narrative hops around between the two characters as they search for the yakruna, a sacred and possibly mythical plant that lies somewhere in the far flung reaches of the Colombian amazon. The two tales are bracketed by a fictions tribesman named Karamakate (one who tries), who accompanies both of the men in their travels through the beautiful and seemingly boundless Amazon River. The native isolate had secluded himself after the rest of his former tribe had apparently been wiped out, and only he remained.

As the old and admittedly hoary adage goes; it’s not about the destination, it’s about the journey. In a strange way, this is every bit the road movie as Thelma & Louise, except with complex mediations on the importance of community replacing the horrible women and pseudo-feminism. The journey in question is a revelatory experience for characters and audience alike. As our players make their way down the serpent itself, Guerra manages to compartmentalise the precarious but dogged existence of the inexcusably abused natives. The horrors endured, livelihoods and diverse cultural experiences are compressed into 2 hours of exquisitely shot exchanges.

Even if it only most plays out in the background, Guerra doesn’t shy away from acknowledging the irrepressible scars that arise from colonial trauma. In a chilling sequence, Grunberg and his young companion Makunda happen upon a mass grave of a recently thriving tribe, the shallow burial plots decorated with the latex their lives were expended for. A mutilated, one legged native begs to be euthanized. It’s haunting. The Amazon rubber boom left a devastating impact on the indigenous peoples of South America as the wealthy barons exploited the natives to make up for labour shortages. One such plantation of 50,000 Amerindians was left with only 8,000 by the time the killings were discovered. It’s not just the human cost; these are cultures that were being completely eviscerated. The bifurcated narrative serves a purpose in this respect, as the Schultes story exposes the consequences of the damage done thirty years prior. Grunbergs expedition overnights at a cruel, monk run monastery that is eager to convert the young “paganist cannibals”, but when Schultes arrives at the same spot in 1940, what remains is an remote community run by a fanatical zealot. Their faith is a disturbingly maligned version of Christianity, complete with a messiah complex for a leader, who calls himself Christ and “the redeemer of the Indians”.

Guerra, however, is not an unrelenting cynic and is eager to demonstrate that cross-cultural dialogue is not a wholly worthless enterprise. Elements from one another’s cultures like language, photographs, classical music and ritualistic dances can be shown to be shared without serious consequence. Karamakate is the films staunch moral compass. Guerra uses him a device to have us re-evaluate the position of “the noble savage” and realise that, contrary to thinking at the time, ignorance was far more pervasive amongst the white man than it was amongst the natives. The burden of understating, it would seem, lies not with the oppressed but with the oppressors.

Grunberg is deeply compassionate man, who is desperate to preserve the native the way of life, sometimes to a fault – he’s horrified when one tribe leader steals his compass and that they might discover how to use it. It’s Nilbio Torres, the actor who plays the young Karamakate, who stands apart as something of a revelation here. Torres, a native who never acted before, affords the character with a distrusting thousand yard stare that stays with the viewer long after the credits. It’s a mesmerising performance and one that feels anything but insincere. The character is a fascinating creation, who’s self-isolation speaks volumes about both the crippling loneliness of a life without a people but also of the sheer determination shown by indigenous peoples to preserve a fading way of life.

More than just a cerebral showpiece, Embrace of The serpent is also one of the most visually arresting films of the year. Like Herzog and Coppola, Guerra did it the hard way. Choosing to stick to 35mm film over digital in a gruelling environment, it pays dividends here. The decision to film in black and white also seems, at first glance, like a ludicrous one, considering the Amazonian rainforest is one of the most infamously colour-rich landscapes known to man. Guerra knows however, that these regions have been covered conventionally in cinema for years and the crystal clear, monochromatic imagery reignites the senses by giving the region a new kind of sparse, other worldly beauty. By the time we see the towering, quite stunning mounds of the Cerros De Mavecure at the film’s end, we start to see the mythic quality in the land feature the same way the natives do.

Embrace of the Serpent was nominated for the best foreign language feature at Academy Awards this year. It didn’t win. It’s quite fitting really. The film it lost out to be the equally great and deserving Son of Saul, a great picture about a much more recognised genocide; the holocaust. Like the indigenous peoples in this supreme piece of filmmaking, the movie finds itself not getting the attention is sorely deserves. Just before the credits roll, we learn it’s dedicated, unsurprisingly, to not only the tribes we know about but the ones we may never know about (Grunberg’s and Schultes’ writings are the only known records of many of these tribes). This is not just a great film because it provides a voice for the voiceless, but also because it acts a sobering reminder that some voices will never be heard.

Embrace of the Serpent is in selected cinemas from Friday June 10th. Check out the trailer below.

[youtube id=”4ff7TcnqHUc” align=”center” autoplay=”no” maxwidth=”750"]

Featured Image Credit