Christopher Nolan is Making the Wrong Movies

This is a rant. Yes, I’m swimming a bit against the stream here/maaaaybe borderline contrarian. Christopher Nolan is now the Oscar frontrunner and Dunkirk is universally acclaimed. Here’s the thing though – I believe he’s a strong director BUT with a specific set of talents, and he’s choosing to ignore those. Nolan is extremely talented at depicting psychological conflicts, keeping a convoluted plot centred on a core emotion, and directing tense confrontation scenes. He’s surprisingly poor at spectacle, action, and ‘big ideas’. Looking back, there’s a very obvious break point where he became convinced he was a great director of intellectual spectacle.

Early Nolan

Leading up to The Dark Knight trilogy, you can see a clear thematic spine in Nolan’s movies. Memento, Following, The Prestige and Insomnia all follow a protagonist and antagonist locked into an obsessive conflict, a psychological entanglement where the line is blurred as to who is actually generating the conflict. Let’s take another look at Memento – Leonard has made his mission to find his wife’s killer (John G) the centre of his life, but the world around him is constantly shifting due to his mental condition. As a result he sets up a system to bring order to it – polaroids, tattoos, and maps – and pursues that with a blinkered determination. Then the rug pull at the end – he’s already killed John G plenty of times, and he’s never remembered. There may not have even been a murder to begin with. The reason for the conflict isn’t because of John G, it’s because of Leonard. There’s a void inside Leonard, and to fill it he needs this conflict to give his life meaning. Otherwise he’s just an amnesiac doddering about, incapable of leading a full life.

Conflicts in Nolan’s early movies are never straightforward, and rather than being simply a thing the hero engages in, they’re more like a cursed narrative the hero becomes embroiled in due to a personal failing. Pacino’s inability to go public with his guilt in Insomnia, then lets a murderer off the hook. From that point on the two become tethered together in a kind of ‘endless dance’ of conflict. This dance of conflict is the centre of The Prestige, where Borden and Angier are locked into a rivalry that costs them happiness, love, and ultimately their lives. Their conflict is due to something irrational – a secret to a trick – that either can simply give up on at any point but the force of obsession compels them to continue. Nolan’s heroes are often unable to extricate themselves from the conflict because it means so much to their identity.

I recently re-watched The Prestige and was surprised by how – with the twist already known – it plays as a really heartbreaking drama detailing the cost of obsession. As Bale’s Borden says, he ‘lived half a full life’ in order to pull off his trick. His and Angier’s rivalry taints and destroys every one of their other relationships. Similarly with Memento, watching it again with full knowledge of the twists, it’s a haunting exploration of grief. In early Nolan there might be complicated plotting and time shifts, but at its centre – beneath all the tricks – there is a surprisingly strong emotional core.

When I was talking with a friend about Dunkirk she said something telling – ‘Ugh, I can just imagine him, like a boring Uncle, looking over a big map with little boats everywhere feeling so proud he knows where everything is at every time. With a fucking stopwatch in his hand’. Before Nolan was this planner who felt his intricate plans were valuable in and of themselves, he made interesting movies about such figures. Leonard with his tattoos, Angier with his Tesla plans, Dormer with his detective skills – all going to extreme lengths to wrestle a chaotic situation into order. The lengths they go to push them into morally dubious territory, and often beg the question – is their need for order not a little insane?

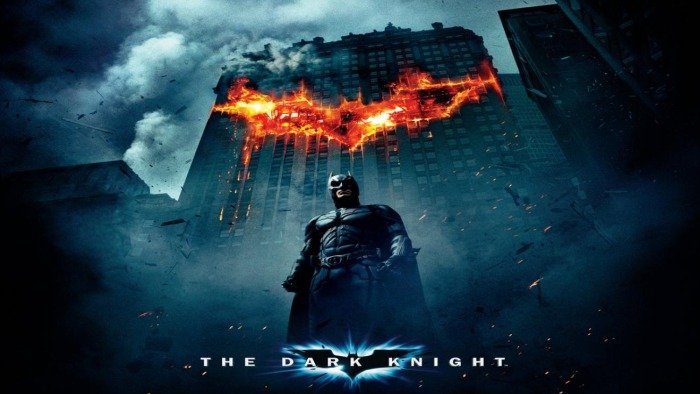

Of course, you can see where I’m going with this. With The Dark Knight, Nolan created another one of these movies, but on a far bigger scale. I think it succeeds as a distillation of Nolan’s early themes, not due to any particular flair for action or spectacle. The big problem in Nolan’s career has been that he took the film’s success as a validation of his ability to stage spectacular action scenes and wrestle with big ideas, and has lost track of the strengths that really enlivened the film.

I think the knot that holds TDK together is the central feeling of Batman as an obsessive planner. In the first movie he’s reordered himself internally to become a hero, and when TDK begins he’s almost completely ordered the world around him into coherence. For the first 30 minutes Gotham is so precisely locked down through his ominous presence, it’s like the world in The Lego Movie if the villain had succeeded in covering everything in Krazy Glue. Once the Joker begins to disrupt his plans, he doubles down on this precise planning – we have this wonderfully tense/silly escalation of planning – taking shattered bullets and reconstructing them, scanning the city for voice patterns, and finally hacking into private cellphones of every citizen. He’s like a little kid who organises a really structured birthday party and when it starts going wrong – when someone jumps on the bouncy castle before they were meant to – he runs around frantically trying to put everything back into order. Batman is a hero who typifies the idea of laconic order as a masculine ideal, and TDK sees that ideal being pushed to a deranged extreme.

The action scenes are routine/somewhat-incoherent (see this video for a full breakdown of one scene), but I’d argue they work because Nolan knows one vital thing – why an action scene happens is just as important as how it does: by aligning the audience with the clear motivations of the hero, the action stemming from them become more engaging. The real standout scenes, though, are the confrontations centred on psychological conflict. The interrogation scene between Batman and the Joker is the super-charged heart of the movie. All the ideas are laid bare but in a way that feels dramatic, not didactic – the worth of order, morality and justice are all brought into question, without coming off as pretentious waffle. Once more that sense of planning and control intensifying into hysteria is there. Joker’s lines could be said to any of the early Nolan heroes ‘you have all these rules and you think they’ll save you’. Commissioner Gordon watches and asserts ‘He’s in control’ as he and his police force watch the hero spiral out of control and brutally beat a prisoner.

Later Nolan

Since then, the movies have drifted further and further from these core elements, to diminishing returns. With Dark Knight Rises, Inception, Interstellar and (I promise) Dunkirk, Nolan has created movies that have an initial high impact critically and then are largely forgotten – start out 9/10 and end up feeling like a 6/10 two years down the line. There’s no lasting power in them because for all the dazzling complications of their plotting, there’s nothing interesting at their centre. Inception now plays like an overlong video game tutorial, before finishing on a third act spectacle that fails completely to capture any of the elements of actual dreams. It’s like a movie about dreams by someone who’s never had one. Somehow dreams stick to a grid system? And are emotionally continuous and whole? In about five minutes Inside Out gave us a much smarter depiction of dreaming than Inception did in its 2 1/2 hours. And Interstellar wants so desperately to be a Kubrick movie only to throw everything out the window because of ‘love’. For gods sake. And does anyone in that world know any other poem except ‘Do not go gentle’…

Which brings me on to Dunkirk. I’ll admit I saw it in a tiny theatre in Ohio, so maybe an IMAX viewing will change my mind, but it just felt so damn flat. The 3 time-frames technique came off as pretentious, needlessly confusing, and ultimately failed to have any resounding effect on me. Nolan, now sole writer, has completely stripped away the psychological centre of his movies, and replaced them with basic stick men who bring us through set pieces that are meant to be both spectacular and intimate. Tommy – the kid in the ‘mole’ plot – is less a character and more a handy device to bring us from one sinking ship to another. The style aims high – David Lean meets Terrence Malick – and falls between two stools. For 2/3 of the movie it’s dispassionately poetic, close and often handheld – simply following, not emotionally guiding you – and then suddenly the little boats are coming up the shoreline and it bursts into hand-on-heart patriotic & sentimental gloop. I don’t mind either style, but the shift from an extended Hans Zimmer music video to an emotional and jingoistic finale felt clunky.

I don’t think this is an isolated phenomenon – lots of incredible directors have spent large parts of their careers trying to make movies utterly unlike their strongest work. Woody Allen tries to make a Bergman movie at least once a decade. And while I love Hitchcock movies, I’d argue his later work (The Birds, Marnie) indulges in character drama psychobabble with overlong dialogue scenes, leaning on his weaknesses as a director, rather than his strengths of cinematic storytelling and suspense. More recently Ridley Scott shows an astonishing command of mood and atmosphere in Alien, Blade Runner and Gladiator, which he mistook for an ability to create epic films with spectacular special effects, leading to Alien Covenant, Kingdom of Heaven and Gods of Egypt. Of course, it’s good for an artist to challenge themselves – I think Scorsese’s created some of his best work running away from his image as a gangster movie director – but in Nolan’s case the returns have become less interesting with every new title.

Which begs the question – what should he be doing? I think the ideal Nolan movie isn’t a grand spectacle, but a close and intimate crime movie. If Heat hadn’t already been made that would be a perfect script for his talents. He clearly loves heists and film noir, they’ve all the main Nolan things – a planner! complicated plotting! murky morality! So if he happens to need advice, mine would be – just go back to basics, work with your genuinely-talented-writer brother again, and make an excellent movie for a change.