Film Review | Breathe is a Story Worth Telling

One of mankind’s greatest achievements of the 20th century may have been the near eradication of the polio virus. An awful killer, the disease could be spread through the air and in some instances left its victims in a permanent state of paralysis from the neck down once it left their system. Not too many generations ago, the ghastly sight of rows of patients, left as husks in iron lung machines was a common one in most western nations. In the cases like this, life expectancy was mere months. Andy Serkis’ decent directorial debut Breathe is a story about an expectation that became the norm through sheer force of will.

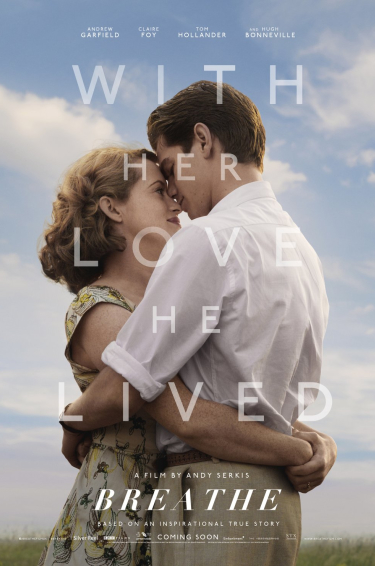

Andrew Garfield stars as real-life Robin Cavendish, who, in the late 1950s, contracted polio while working in Kenya at the age of 28. Cavendish ended up permanently immobilised from the neck down, and would rely on a mechanical respirator to keep him alive for the rest of his life. On returning to England with his wife Diana (a gutsy Claire Foy), he ends up in hospital, with a dire prognosis as it appears he will spend the rest of his limited days in a bed. Longing for death, he begs his peers and others to help assist in his suicide. Diana won’t hear of it and instead does everything she can to get him out of the dreary setting and into a new home they can share together.

It is in the first act that the emotional weight of the film is at its most forceful. Diana displays a superhuman devotion to Richard, with Foy being something of a doting and hyper-positive force of nature. Garfield too, once again, proves why he’s one of the best young actors of his generation. After coming off stellar but distinctly different turns in Hacksaw Ridge and Silence, his work is just as exemplary here. Robin Cavendish’s arc, from well-meaning toff, to suicidal invalid and then to inspiring advocate would be a tricky path for any actor, let alone for someone who can only use their facial features for about 90 percent of the runtime.

For his time, Cavendish was a medical marvel. It was unheard of that people with his condition would ever leave the care of the professional, hospital staff. There is, of course, the archetypal scene of a stuffy chief lambasting the couple in cartoonish fashion for the decision, but Cavendish doesn’t just end up bed-bound on a respirator, he was he first person with his disability who was able leave the confinement of one room due to a prototype wheelchair designed by close friend and inventor Teddy Hall (Hugh Bonneville). It’s strange to think that one act of ingenuity ended up having a profound effect of the lives of countless people who endured a similar fate.

The second and third acts are where the film starts straining to fill its narrative with happenings of note. There are certainly the standout moments of genuine heartache, with one sequence of Cavendish visiting a supposedly state of the art institution for dealing with the physically disabled being particularly moving. The German doctors, proud of imprisoning their patients into the walls of the hospital, are shocked to see a man of Cavendish’s condition moving so freely. But other asides, like a pointless family trip to Spain and lifeless garden parties feel more like runtime padding than anything else. Side characters are a mixed bag and generally underdeveloped too. Tom Hollander plays a nauseatingly pointless pair of twins that seem to exist only for cheap comic relief and to show off mostly unimpressive CGI work.

Director Andy Serkis is of course most well-known for his motion capture work and his direction here is workmanlike, without all that much fault or merit to speak of. To his credit, Foy and Garfield transcend any moments that might veer into stodgy sentimentality. While it’s not well explored prior to the illness, their relationship is still a sincere portrait of love at its most arduously earned.

Robin Cavendish’s life story is the kind that nobody knows but everybody really should. His tireless work in later life, campaigning for those like him, had an impact that few may have noticed but many would have seen. Breathe is an imperfect film, but it’s a tale worth telling and sometimes just telling that tale can be enough.