Keaton’s Batman Begins | Batman at 30

I’ve seen the future and it will be.

Batman 1989 turns thirty this week, and three decades in it remains as odd as it was when it was released – it’s been criticised as having been the ultimate studio product, pumped out with the greatest of committee-driven effort, a great big collage of different plotless ideas all vying for attention resulting in a mish-mash that is only accidentally watchable. Unlike its successor, Tim Burton didn’t have a say on how much of this film was produced, and a crippling writers’ strike led to on-the-fly rewrites. Nevertheless, its boldness set the tone for the blockbuster model forevermore (every Marvel and DC film today owes its beating heart to this film) and its inky black reinvention of Batman on screen cast the mould for every subsequent incarnation. While it’s still a riotously silly film, it has a psychological reality to it that lives beyond even the most ambitious contemporary superhero films. Combined with masterful production design, an iconic musical score and electrifying performances by the two leads, the film is both a timeless gothic opera and the ultimate pop snapshot of the decade in which it was made.

Enduring a decade in production hell, the film finally came to life under Burton (then just 29) who was fascinated by the strangeness of the core – a man being compelled to dress up as a bat to fight evil. While the marketing blitz desperately attempted to distance the film from the iconic 1966 series, it’s clear that Burton embraced it to some extent as well. The idea of the Joker trashing an art museum and fancying himself an artist comes directly from the Adam West show (as does the central plot of the Penguin running for mayor, which happened in the sequel).

The film isn’t Taxi Driver and it doesn’t claim to be. Burton still employs the righteous goofiness that makes so much of Batman’s world fun (themed goons in matching uniforms, gloopy vats of chemicals, bat-shaped gadgets and vehicles). But it’s all tempered by a feeling of oppression and hopelessness. Gotham City is no longer merely the NYC proxy of the comics, but a hateful noirish industrial nightmare. Angular, violent-looking buildings loom over the streets; thick plumes of steam crack through the concrete; grotesque pipes crawl and twist around buildings like bronze tendrils; lonesome leathery punks roam the streets alongside old-timey gangsters and sullen muggers. Batman and the Joker feel like natural by-products of a place so horrible. Production designer Anton Furst shaped the look of Gotham forevermore and his Academy Award-winning work remains unmatched.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VBI47SU-Oqo

While not the title character, Jack Nicholson’s star power gave him top billing and equal screentime to the Dark Knight himself. It’s terribly obvious why – he brings Burton’s signature blend of nightmarish schadenfreude to what could have been a very stuffy film. Admittedly more pantomime than his successors, Nicholson’s raw charisma carries his performance as he journeys from standard-Nicholson-mobster to insane clown on a self-serving crusade to attack vanity and consumerism in a way that’s only funny to him. And he has the best Joker laugh of them all (even better, I would argue, than Mark Hamill).

Kim Basinger plays the put-upon love interest as best she can (I love the movie, but it’s still from an era that wasn’t kind to female characters) injecting warmth and compassion to what could have been a very flat character. Robert Wuhl is annoying but fun as sleazy reporter Alexander Knox. The cadaverous Michael Gough (a Hammer horror veteran – Burton was a big fan) plays a weary, maternal Alfred desperate to facilitate his master’s escape from this burden he’s seemingly placed upon himself before it’s too late (“I do NOT wish to spend my few remaining years mourning the loss of old friends…or their sons.”). Billy Dee Williams sets the sequel stage with a delightfully cool Harvey Dent performance that was never capitalised on in future films (Joel Schumacher infamously swapped him out for Tommy Lee Jones six years later). Pat Hingle plays the most forgettable and inept version of Commissioner Gordon yet.

But the film’s masterstroke is its protagonist. The great paradox of Batman is that we are always told how mysterious he is and yet almost every incarnation shows a hero who wears his heart on his sleeve and is always shown as having wholly noble intentions. While other characters always call his motives and his actions into question, he is always justified by the framework of the story.

In Tim Burton’s Batman, however, it’s never made clear whether or not the film believes in what Michael Keaton’s tortured Bruce Wayne is doing. As Bruce, Keaton is soft spoken, only speaking when entirely necessary – personable and charming sure, but not entirely friendly. He paints the picture of a man so driven, he’s lost in his own world of crime fighting to the extent that he doesn’t really know how to be a normal person (leaving glasses of champagne on unsteady perches, fumbling his words, forgetting that he’s never set foot in palatial rooms in his own home and sporting a hairstyle so unnatural it looks as though it could be served as fairground confectionary). His bumbling weirdness belies a pitch black intensity.

When we see him in costume as Batman in the inky-black armour (eschewing the blue and grey spandex of the comics), he seems far more comfortable in his own skin. The mask appears perfectly molded around the features of his face, particularly his angular eyebrows. Despite the enormous discomfort it caused him, Keaton manages to speak volumes with subtle expressions and slight movements. The fight scenes are primitive to the point of being almost laughable in 2019. Yet, so imposing is Keaton in the suit that they are almost unnecessary. As Nicholson correctly assumed, the suit really does the work.

This is one of the most ruthless versions of the character and his motivations are never made clear. Is he doing this for justice or simply revenge? Is he trying to stop these criminals or does he really just want to hurt them, to make them afraid, to make them pay? Unlike other incarnations where Batman pushes his ethical boundaries over time, this Batman seems to have crossed a line from the outset. In fact, we’re told that he may have dropped a low level crook four storeys to his death. Meanwhile, in another early scene, we see Bruce Wayne using hidden security cameras to spy on the guests of his party via the computer in the Batcave.

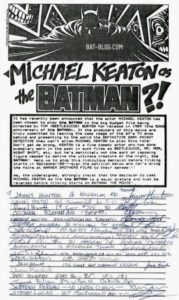

There’s no struggle for this Dark Knight, no turmoil, no humanity – this is how it is. It’s not a perfect world. For all of Christopher Nolan‘s talk of realism and for all of Zack Snyder’s ranting about coolness, there is not one scene filmed by any other actor, not a single one, where Batman is better or more real than he was as played by Michael Keaton. There should be no greater irony than the fact that when Keaton was cast, 35,000 idiots petitioned against it. Google “Michael Keaton Batman petition” in 2019 and instead you’ll find an assortment of change.org petitions wholeheartedly pleading for his return.

The film is far from perfect. Stodgy pacing and ramshackled rewrites result in a midsection that is occasionally confusing and sometimes teetering on boring. An ambitious but ridiculous chase scene involving Batman on a horse and Joker killing Robin’s parents was understandably omitted. But as a result the second act of the film is lacking blockbuster cred.

Prince’s tie-in soundtrack is so omnipresent that it pollutes the film as often as it enhances it. As wonderful as Nicholson is, he’s given about five minutes too much screentime leaving the viewer wishing we could get back to the other characters. And while Keaton’s Batman is wonderful, it would have been nice to see him (or a Batsuited stuntperson) engage in some slightly more ambitious fight scenes. The film’s Burton-fu sees him just sort of hobbling around with his hands in the air.

The film also begins the Caped Crusader’s troubled relationship with onscreen murder. While a lack of bloodshed is one of the hallmarks of the character’s code of conduct in the comics, almost every live action appearance starting with this film sees him permanently dispatching a dastardly foe or twelve. While the murderizing is nowhere near as gleeful as it appears to be in the subsequent film (or the recent Zack Snyder rubbish) it’s never an easy pill to swallow.

Still none of these flaws ever entirely detract from the enjoyment of the weird adventure. From the performances to the production design to the music and the cinematography, Batman is a film so rich that even having watched it 75,000 times I spot amazing new details every time – from the ‘Axis’ sign being just about visible on the breathtaking exterior of the chemical plant to Nic’s shark-tooth earring to the ‘avoid pickpockets’ sign behind Vicki as she exits her car.

I’ve seen the movie so many times over the past 30 years that I can quote every single line of dialogue. It’s become less of a film to me at all and more of a living entity that grows and evolves as I do – it’s fitting that it and I are the same age. It’s sensationally flawed. There are better Batman movies. There are even better Tim Burton films. But it is undoubtedly and unavoidably my favourite movie ever made. I’ve been watching it for 30 years and I’ll watch it for 30 more. I’ve seen the future and it will be. I’ve seen the future and it works.