Art Encounters | The Eyes of Dunkirk

Note: This piece contains spoilers for Dunkirk

It’s early August. I’m in the middle of trying to finish a load of writing projects, one of which is a book on film. I need a break, just to remind myself of why I’m doing what I do. I see somewhere that Christopher’s Nolan’s Dunkirk is opening in the cinema. My thing is cinema; I’m about to finish a book about film. My hero is a French filmmaker called Robert Bresson who very few people in English-speaking countries know of and much of this book I’m writing is about Bresson. But Dunkirk is opening, I need a break, and it’s on my doorstep. And yet even though I need a break the last thing I think I need when taking this break is a Christopher Nolan film; now, at this particular moment in time. Because I just don’t get Christopher Nolan. I get a lot of mainstream stuff. But I don’t get Christopher Nolan. But I still go to the cinema to see Dunkirk and begin thinking about Bresson and a set of eyes. And I start to think that maybe Nolan was thinking about Bresson as well when filming these eyes.

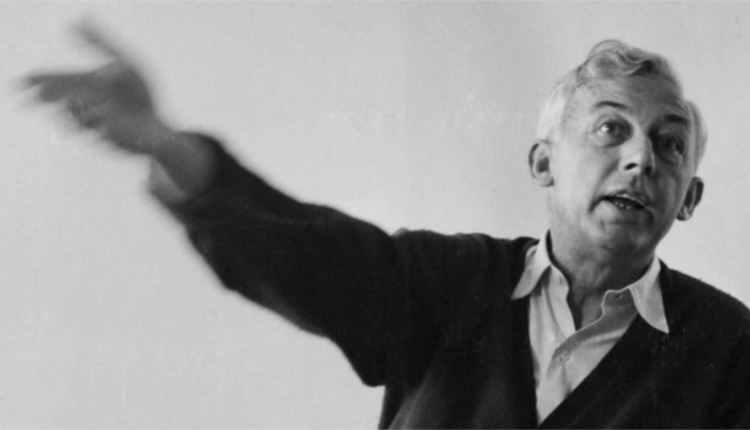

We need to go back in time a bit. I’m sitting in a pub in Dundee having spoken at a conference called Film-Philosophy that was populated mainly by academics. I leave a little weary and let down. But before leaving I stop off in the pub with a TV director who was attending the conference, when he tells me of his interest in Robert Bresson’s book Notes on Cinematography; a small little book of notes that Bresson took during his filmmaking career that was published in English for the first time in 1975. I knew of this book as someone who studied Film. You can’t not know of it. I also knew of Bresson as someone who made austere films that were hugely influential on the direction of European cinema from the 1950 onwards, but who not a lot of people in English speaking countries knew of. When I spoke with this TV director over a few pints, he told me that he had been obsessed with Bresson’s little book since going to film school and had gone to the conference hoping to learn more about this little book. He was disappointed with the conference. I was working on a book about cinema at the time that would use an image from Lynne Ramsay’s We Need To Talk About Kevin for its cover. I later found out that Lynne also spoke a lot about the influence Bresson’s little book had on her as a student. So, when I left Dundee that day I was intrigued. I wanted to know more. I went home to Ireland and bought a copy of Bresson’s Notes on Cinematography. I saw then it’s the second most influential book ever written on film; the outcome of a poll or other I found on-line.

The book began to obsess me. But the last thing I expected when I went to see Christopher Nolan’s Dunkirk was curiosity piqued regarding this book. It’s worth stressing that even though I found Nolan films irritating, I seemed to keep coming back to them. Maybe on some level I hoped for something. I had left The Dark Knight a few years before thinking it can’t get any worse. Memento had left me cold. Watching Inception I thought it tried too hard; I fell asleep half way through. I always got the impression from Christopher Nolan films that something needed tweaking; a more is less approach might benefit everyone. So when I went to see Dunkirk I expected good snooze material. You know the way a sleep at the cinema feels so good? It makes other power naps pale in comparison. But then I got something completely different: I found the little book where I least expected to find it.

What happened then? The truth is I found myself welling up with tears as a pilot whose eyes were all I could see throughout the majority of the film ran out of gas, and I became conscious of his impending death. I read later that Tom Hardy is one of the stars of the film, and was surprised, as I had no recollection of seeing Tom Hardy in Dunkirk. Tom Hardy – I learned – is the pilot whose eyes I saw on screen. As I sat in the cinema watching the plane glide through the air, the engine having gone dead, I found myself sobbing against my will. I began to question why I would cry about someone who is known to me as a pair of eyes on screen? How could something like this happen? And what was the link between this moment and Bresson?

Bresson stopped using professional actors at a later point in his career, when he matured as a filmmaker. He believed that professional actors distracted from the story. Professional actors had originated in the theatre and, according to Bresson, had perfected the art of being someone else. Bresson wanted the modèle, the term he devised for non-professional actors in his films, to just be themselves. Professional actors, he argued, take centre stage so we identify with them and how they feel. But the modèle, Bresson writes, is in the background; so we identify with the condition they find themselves in. Although Tom Hardy plays the pilot in Dunkirk the fact I never knew it’s him is important. I experienced his presence as a pair of eyes like I experience the presence of a modèle in Bresson’s films. It was if Tom Hardy wasn’t Tom Hardy at all. It was just eyes on screen that could have been anybody’s eyes on screen; a cipher of sorts. Notes on Cinematography, made up of short notes about acting and filming, challenges us to think about these aspects of film specifically. ‘See beings and things in their separate parts,’ Bresson writes in the text (as just one example from the book), and ‘render them independent in order to give them a new dependence.’

This is just one short example of what Bresson wants film to do, but it’s a short insight that helps us to understand why a pair of eyes could have been anyone’s eyes. In this note Bresson looks to capture the independence of beings on film, but so that a new dependence forms around them in the course of the film experience. No small feat I hear you say. But this, in my estimation, brings me back to the eyes of Dunkirk as I experienced them that day: the eyes of Tom Hardy that I didn’t know were the eyes of Tom Hardy. If I had known they were Tom Hardy’s eyes in advance, I wonder, would my experience have been altered? Would Dunkirk have been a story about a pilot played by Tom Hardy, and on some level understood as ‘just a film’ with Tom Hardy acting in it? And would I have been as affected by the eyes and everything that was around them?

The thing is I went to see Dunkirk in the cinema expecting to struggle with all these glitzy well-known actors and went away having not struggled with them at all. But because I was taken into the film via a set of abstracted eyes, I wondered if I had been sucked into the general plight of Dunkirk as opposed to the plight of one person. By identifying with a struggle, rather than obsessing over the role Tom Hardy was playing, the eyes of Tom Hardy – as opposed to Tom Hardy as a character – drew me in. I didn’t fantasize about being the character Tom Hardy plays. Unlike when I watch Clint Eastwood and feel a desire to be all macho, silent and uber-masculine like him, I didn’t fantasize about being Limerick’s answer to Tom Hardy. Certain films, I should add, attract me at the level of fantasy. I have no qualms in admitting I tune in to Game of Thrones to keep my fantasy that John Snow is a variation of me alive (I was christened John after all). I tune in every week for this precise reason. But the feeling of sadness when a character like John Snow dies results from my fantasy dying as well. It’s not because I feel affected by his plight. My fantasy alter-ego has come to an unnecessary end. But I experienced Dunkirk differently. I got all weepy for other reasons. I wasn’t sad because these were the eyes of someone facing imminent death. I was saddened because everything around these eyes was dependent on them. I felt – in this moment – I understood the new dependence Bresson writes about.

I reacted to the eyes of Dunkirk because they helped me feel a plight more generally: the fact a pilot had risked death to help others. As I left the cinema I began thinking of the pilot’s predicament as a microcosm for life. That just like the pilot in his own little portal as a set of eyes, I too am a set of eyes trying to navigate, trying not to crash, yet not knowing the extent my decisions will affect the others who depend on me. As the plane flew over Dunkirk, empty of fuel, and the mass evacuation had come to an end, I came to feel the plight as my own. I thought of the plane as standing in for my life; the set of eyes looking out at me as my own. But I also began to think of all the soldiers who had been evacuated from Dunkirk as having depended on these eyes from the plane, forming that kind of new dependency that Bresson writes about.

It was in a moment of wonder then, that moment when an artwork touches us in some way, that I began turning the lens in upon myself, letting my imagination run free in the moment. Suddenly I felt I like a pilot flying around in the sky, except those I have to save, and the things that are dependent on me, differ in kind. And this feeling would give birth to an image I remember clearly: I’m in an aircraft of my own, buoyed with the task of navigating all those who are dear to me to safety, when there is a blast of turbulence all around the plane. I wonder will I land safely? Should I risk everything for the people I love? It was only when awakening from this little daydream into the present that I saw the plane land on the beach on screen, I looked over at my son Anton sipping on the last drops of his Pepsi and I felt as if, almost magically, I had become the eyes I was watching on screen. The eyes of Dunkirk became – in that moment – my eyes. I had gone to the cinema that day thinking that I’d have the usual Christopher Nolan experience, let down by a feeling that things just aren’t right; that something isn’t quite right about the film. I didn’t expect to come away feeling so moved by a pair of eyes, looking out from a cockpit. But the reason I felt this way is I had imagined the eyes on screen to be my own, as my life became a cockpit, an individual thing, and I an individual being around which all new dependencies were forming. I didn’t fantasize about being Tom Hardy, heroically saving others. I felt momentarily that Tom Hardy’s eyes were actually my own.

Perhaps cinema is unique in activating such experiences. And this is the reason Susan Sontag, probably the greatest critic of the twentieth century, revered Bresson above all other filmmakers. Maybe it’s the reason Notes on Cinematography is a bible of sorts for film students. And maybe it is also the reason Bresson’s ideas aren’t easily enacted; it’s why the director I met that day in Dundee revered the little book and yet lamented the fact that he couldn’t draw from its principles that easily in making TV. He couldn’t make a TV program about a set of eyes. But if there is a moral, in my view, it’s that we are more often than not taken up with wanting to be someone else, which TV usually caters for. On rare occasions we get a fleeting glimpse of something otherwise: to experience another’s plight as our own. As opposed to just acquiring more things, these fleeting moments enable us to keep going, to keep flying our little plane in the sky. And it is these rare moments that are the real victories in life; when we hop out of our cockpit and into another’s and we get a sense of what it’s like to see from another’s point of view.

Dunkirk is in cinemas now. It is reviewed here.