Film Review | Hungarian High Noon in 1945

In his latest film 1945, Hungarian director Ferenc Török poses the question: What happened when Jewish citizens returned to communities they were transported from during World War II?

On a hot summer’s day in a rural Hungarian town, preparations are underway for the wedding of the town clerk’s son and a local peasant girl. The town clerk (Péter Rudolf) is all slippery and officious bonhomie, while his laudanum-addicted wife (Eszter Nagy-Kálózy) is determined to talk her son (Bence Tasnadi) out of the nuptials and derail the plans of the grasping bride-to-be (Dóra Sztarenki), whose heart is still entangled with a former lover (Tamás Szabó Kimmel) while her eye is firmly fixed on the family’s thriving shop.

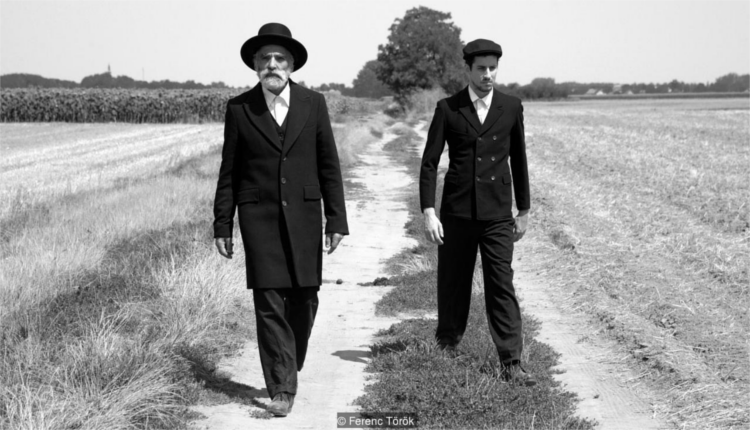

The occasion is disturbed by the arrival of a father and son at the nearby train station, (Iván Angelus and Marcell Nagy), along with two wooden crates. The stationmaster recognises them as Jewish, but they are not local – the town’s Jewish community was deported during the Nazi invasion in 1944. The purpose of their visit is unclear – do they bring goods to sell or have they come on behalf of the town’s former occupants? The stationmaster panics and rushes off to warn the town.

Thus, the scene is set. Who are the strangers? Why are they there? What does it mean for the townspeople and how will they react? While the strangers walk slowly behind the horse and cart carrying the mysterious crates, the news permeates, and the townspeople’s varying degrees of complicity in the expulsion of their Jewish neighbours is gradually revealed, to the countdown clip-clop of hoofbeats.

Filmed in high contrast black and white, the film draws heavily on the American western – the bride to be in her traditional wedding dress is a spit for Grace Kelly in High Noon, the townspeople shoot loaded glances with the rapidity of a Morricone stand-off. As in the recent Irish famine movie, Black 47, the western now appears to be the go-to genre for the ‘Behold the pain of my people’ film, a mechanism for exploring difficult times.

The idea of Jews returning to the homes they were expelled from, at the end of the war, exposing the collective sins of these communities, is one charged with tension – the idea was developed from a short story Homecoming by Gábor T. Szántó, who also co-wrote the script. Appropriation of Jewish property and belongings was widespread in Hungary, after the transportations to Auschwitz.

However, 1945 strangely misses the mark. It has such potential for psychological drama, yet it feels as if the reins were dropped too quickly and the resulting scenario is not as taut or as nerve-wracking as it might have been. Nonetheless, Péter Rudolf and real-life wife, Eszter Nagy-Kálózy are excellent as the town clerk and his scheming wife, and Sztarenki shines as the young bride caught between the brooding Russian ex-fiance and the financial stability of the clerk’s milksop son.

The real problem is that the Jewish strangers at the heart of the film are non-existent as characters (on IMDB, the son isn’t even named). They are ‘Bogeymen’, who the townspeople immediately identify as Jewish based on ‘a hat and a beard’, and whose phone calls announce, ‘They’re back!’, with no context or explanation.

They remain little more than generic symbols of their faith, ciphers, throughout – we learn nothing of them as human beings, what they’ve experienced or what this journey means to them. With the atrocities of the Holocaust based on dehumanising a race of people, behaviour that’s on the rise again around the world including Hungary, the film’s failure to portray its ‘outsiders’ as anything less than fully-rounded is disconcerting.

This absence could be emblematic of the fate the Jewish people in Hungary – only 25 per cent of Jews survived the Budapest Holocaust and one in three of those who died at Auschwitz were Hungarian. But 1945 doesn’t feel that clever in its intentions – when the final confrontation arrives, the strangers are literally surrounded by villagers with pitchforks.

Visually beautiful, 1945 lacks subtlety in its execution and fails to take an intriguing premise to the psychological climax it deserves.