Art Encounters | I Found Myself Within A Forest Dark

I found myself within a forest dark….

I cannot well repeat how there I entered,

So full was I of slumber at that moment,

Dante’s Inferno, Canto 1.

I’m lying on the bed in the converted attic of my new abode in the country; or at least ‘the country’ if we can call it this when in distance of a village. The last month has been chaotic: moving house at Xmas, with family in tow, is many of us’s idea of a nightmare. But I’m sure moving house in summer is still bad, and autumn, and spring. I now live in what’s technically, at least as far as it can be in Ireland, a ‘woods;’ the house is surrounded by trees, a series of hills that I like to think are mountains. My neighbour is an 88-year-old man who once played hurling with Christy Ring for Cork. It’s a world I’m not-too-familiar with, but one beginning to feel like home. And I’m unpacking art that I had put away in an attic fearing my kids would knock it off the wall. Time, however, has changed things and the kids, growing up as they do, prowl the home in different ways. Now that I feel safe to put stuff up, I’ve got three pictures of horses between my kitchen and sitting room; one ceramic plate, one print, and one photograph; and I don’t even know much about horses. I suppose there’s something ‘random’ about why we put things on walls.

Among the works (that lie in a corner of the sitting room) I have gathered is a large-scale silicon diamond mount photographic print titled Forest 1 that was given to me by my colleague and friend, the artist Lorraine Neeson. The work was a very generous gift in exchange for an unpublished catalogue essay I had once written for a solo show of Lorraine’s to which I had given the somewhat pretentious title ‘Deconstruction after Deconstruction.’ The photograph is a night scene of a wooded area, with only a small lit-up clearing visible against the pitch-black and an all consuming, impenetrable darkness. This little opening, which suggests a bright light has been shone on the space by the artist to make the clearing visible, and which – as a result – generates a certain curiosity about the actual making of the image itself, is like a light shining from, as Wittgenstein once said of Connemara, a pool of darkness. It’s a night scene in the very place we don’t expect to see one. And yet while the process involved in the making of the image brings forth an initial curiosity, it is curiosity that subsides, turning into contemplation, as the image in its ebullience wins us over. In darkness there is always light, the image seems to suggest. But this doesn’t really tell what the image does.

So what does the image do? Simply put, it prods us; and keeps prodding us. And perhaps this is precisely what a work of art is meant to do. Every time I look at Forest 1 – about to stand proud on my sitting room wall – I think of that great essay by Heidegger on the work of art, where he makes the distinction between earth and world. For Heidegger, a work of art should, at its most fundamental level, awaken us to the primordial division between earth and world. Only by prodding, and hence revealing this division as a ‘rift’ can the otherwise affective subtleties that art evokes come to pass. Only when the ‘rift’ reveals itself can the affect of the artwork work its magic. It is no surprise, then, that the metaphor Heidegger returns to over and over again in The Origin of the Work of Art, and many of his later essays, is the clearing in the forest. The clearing, as Heidegger reads it, is a manifestation of world, standing for our emergence out of the darkness of unknowingness into sense. When a clearing is made in the forest, we thus transform the earth into world.

This is a simplistic reduction of Heidegger’s thinking. But it does help us to think about Forest 1 as a work that orients us the viewer back to this primordial division, to prod and poke at feelings that might appear, like the forest, impenetrable in their darkness. In other words, the image isn’t just about a clearing, a light brought to bear on darkness that gives meaning to a more primordial division between earth and world, but the always ongoing process of making sense. We are always looking for a clearing, and this, unlike the image that records a moment in time, transcends any such moment. The never-ending process of making sense is the real constant of the world.

Hence, the origin of art is the rift that draws us in, compelling us to make sense of it. My sense of Forest 1 on Saturday the 14th of January, as I thought about hanging it in my new home, came out of these ruminations. I walked around the house, wondering where to hang the picture, thinking of one room after another; thinking of light and dark, crevices and openings. And then I did what most people do in the 21st century when they think they need a break – a short distraction from the now – I took out my phone. I begin scrolling down through Facebook, through the mindless fog of nothingness, until a post jumps out at me; a notification that had been shared that the author Mark Fisher has died. I’m dumbstruck; not because I knew Mark in person. I didn’t. In fact, I was only recently acquainted with his work, when a peer review for an article I submitted suggested his writings as references. Mark wrote the liner notes for the DVD release of John Akomfrah’s film The Stuart Hall Project, the subject of my own article. In the space of two weeks I devoured everything he had written, from his legendary K-Punk blog, to his edited collection of works on ‘hauntology’ and depression. It was a like a light in a pool of darkness.

The liner notes for The Stuart Hall Project begins with recall of an encounter with a sister project installation Akomfrah made about Stuart Hall, designed to be exhibited in galleries: The Unfinished Conversation. This latter work is presented on two screens, and engages in something of a life biography of the legendary public intellectual, Stuart Hall, based on archives taken from the BBC. Mark focuses on his emotional response to the work in the gallery, how he cried when he first saw it, not because it told a sad story, but because it harked back to a time before Thatcher, and before Neoliberalism, when there was still some semblance of a public, some semblance of belief that television should serve society. It’s a short, beautifully perceptive piece of criticism that marries insight to a genuine sense of compassion. Later, when turning to his other writings I was impressed by the reflections on his own life and struggles to make sense of art and politics, as a springboard for greater societal critique.

But as I sat there that day, caught between the picture and this news, I was taken aback. I recalled the personal detail that pervades Fisher’s writing; the fact that I knew from this he suffered from depression for most of his adult life. In fact, one of the things that made him so heroic in my eyes is that he articulated the experience of depression so well, and from the perspective of the increasing precarious of employment. His series of articles in The Guardian on depression and suicide in the economically and social disfranchised, helped explode a myth perpetuated in so many facets of ‘our’ media: that we should apprehend depression as a chemical imbalance, a learned negativity in apprehending the world, or childhood trauma resurfacing in the form of symptoms. Maybe we should see the affliction as the effect of a winner takes all society; market-oriented values making their presence felt in every facet of life. For those of us told that ‘depression’ is like a light turned on and off, a ‘natural’ change in the weather (like a woods we can sometimes find our way out of, and sometimes not), Mark, in his writings, offered a clearing, shone a light on the forest through which we all stumble.

Mark’s writing is relevant because, like a lot of young men, I suffered from depression in my early twenties – a time in young men’s lives when a seamless transition to adulthood is expected – which resulted in a three month stay in St. Pat’s psychiatric hospital in Dublin. I had just finished a Masters thesis, felt like I had been catapulted from the cocoon of academic pursuit into the unforgiving ‘real world’ in one fell swoop, and was overcome with debilitating self-doubt. I was propelled by a sense of worthlessness and relentless self-loathing, out of which my mind went askew and I spent a number of weeks patrolling a hospital corridor. I yearned, in the early stages, for a doctor to label me. More than anything I wanted a diagnosis of what was ‘wrong,’ blithely unaware that the assumption of guilt, of being wrong, is the not-so-silent voice in depression. Unlike Mark Fisher’s stirring reflections, I never wrote publicly about this experience, never saw it as a symptom of a wider problem of which I was a part. And so Mark’s purposeful, witty scrutiny of the affliction was an arm reaching out in solidarity: you are not alone.

I glance again at the picture, the cold inebriation of shock that comes before real sadness slowly passing, and I see the lit up clearing again, the rest of the frame blackened by the imperious darkness of night. I think of William Styron’s borrowing of the line ‘darkness visible’ from Paradise Lost to title his short but moving memoir about depression. Is it that same ‘darkness visible’ that Styron writes of, which takes the form of a dark forest, that Lorraine’s picture summons us to think about? The same woods that Mark Fisher, whose writing often took the form of a clearing, found himself lost in? I try to make sense of it all but I find myself making sense of a picture that stands before me to, somewhat paradoxically, make sense of it all. Sometimes art, this hard piece of matter that bears no emotion in it essentially, elicits the emotion in us, draws it out. We project on to the object in order to feel as subjects. And when all is said and done, to do this, is to know we are alive.

Later that day, I recall by chance a conversation I had with Lorraine about Mark Fisher’s writings on hauntology, forgetting that Lorraine’s work, and its consistent focus on light and darkness (or is it darkness penetrating light?) is in a kind of dialogue with Fisher’s writings all along: the part of Mark Fisher’s life that will continue to cast a very big shadow on the art world. And I leave wondering if connections are forming all the time, unbeknownst to perception. Only sometimes can we see out of the forest, when somebody’s light shines upon us.

In solidarity with Mark ‘K-Punk’ Fisher (1969-2017).

Current, a solo exhibition by Lorraine Neeson, opens in Sirius Arts Centre, Cobh, Co. Cork on January 21,st running until March 25th.

Featured Image: Forest 1, Lorraine Neeson.

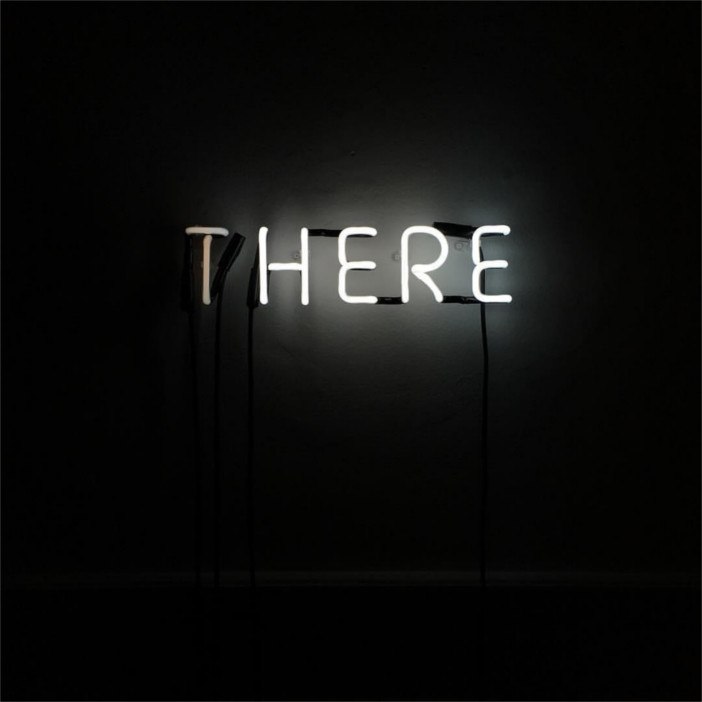

THERE: Medium: Neon, Electrical Cable, Flasher / Programmer

WHERE DO WE GO NOW BUT NOWHERE: Turntables, Vinyl Records, Wood, Speakers, Amplifiers, Electrical Cable, Filament Lightbulb, Programmer