Falling Into Different Places | David Toms In Conversation with Anamaría Crowe Serrano

It is a sign of the health and determination of the Irish poetry scene that a long-time stalwart like Southword magazine is making a return to the world of print, while new magazines like Gorse, Banshee, The Penny Dreadful, The Well Review and Tangerine are establishing themselves as mainstayers of the scene. The emergence of a new publisher of poetry in the shape of Turas Press is also a welcome development. Liz McSkeane’s press promises to be a bold publisher of new Irish work if the early output off the press is anything to go by. I first came across Turas Press online because they have published a new book by one of my favourite Irish poets, Anamaría Crowe Serrano.

My first encounter with Anamaría and her work was many years back at Soundeye. This was an annual poetry festival for Irish and international non-mainstream – innovative or experimental – poets and poetry that ran from 1997 until 2017. As well as a poet, she is a translator of novels and poetry and a teacher of Spanish. Her poetry is concerned with language and how we use it to create and shape meaning in our lives and through art. If her poetry isn’t well known in Ireland it is in part because her work is uncompromisingly different and demanding of the reader. It has a ludic quality to it but is still durable. She has published several chapbooks and collections, most recently onWords and upWords from Shearsman Books in 2017 and now Crunch from Turas Press this year.

Both books display the same dexterity with language that have marked Anamaría’s work since her first collection Femispheres, published in 2008 by Shearsman Books and chapbooks like one columbus leap, published by Corrupt Press. Language in the poetry of Crowe Serrano is not merely a vehicle or tool for self-expression, the words themselves get picked apart and stretched, sat side by side with other words that share sonic qualities as well as “meaning”. Font style in the same poems is used to convey multiple voices and presents opportunities for multiple readings.

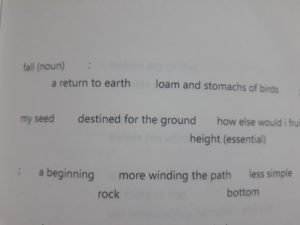

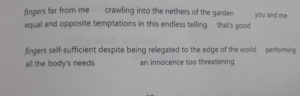

Classic stanzas are dispensed with in favour of using all of the page – this makes the white emptiness of margins all the starker.

The white spaces often offer punctuation of their own in the absence of standard forms. They offer a breath to be taken in what can be a breathless and exhilarating poetic experience. These are poems best enjoyed when read aloud. The challenge is to hear how they sound in order to catch what they mean as well as merely parsing the words and phrasing itself.

Crowe Serrano’s poetry works within the best of the experimental tradition of Irish and European modernism. Surprisingly however, this is in fact Crowe Serrano’s first time publishing a book with an Irish publisher. As she freely confesses herself this is because what she writes doesn’t obviously touch on “Irish themes”, even if there is at least some allusion in Crunch to that most famously experimental of all James Joyce’s’ work Finnegan’s Wake. Anamaría’s poetry challenges the reader to rethink what the function of the page is, what word choice does for all aspects of the poem and how we actually engage with the physical and tactile elements of the book. She is not the first or the only writer working in Ireland today who does this, but she is consistently one of the best poetic innovators working in Ireland at present. As someone who is both Spanish and Irish, her engagement with language is not monocultural but flits across borders. Her strong publication record as a writer of original work and a translator bears this out.

Crunch is in essence a rumination on one of the oldest stories we have: that of Adam, Eve and the apple in the Garden of Eden. Through a daring set of poetic practices she asks pertinent questions about the dynamics of nature and power and ourselves:

The poem opens with a short column poem – a kind of prayer that’s a take on Glory Be To The Father – that is swiftly followed by a concrete poem in colour of an apple. Immediately the reader is pushed to think in new ways about this oldest of stories. Not so much a collection of poems as a long sequence on the same theme, Crunch mixes language, image and numbers to create a rich experience on the page.

I recently caught up with Anamaría over the phone to talk more about Crunch and her process in writing it and what she hopes people will experience by reading the poem and what it means to tackle such a well-known story. One of the things we spent time talking about at length were the ways in which she pulls language apart and goes back to the dictionary to examine the meanings of words, to as she says “disrupt a dictionary entry” and “play to create something a little bit different.”

Anamaría argues that we have to think in a new way about the story of Eve and the Apple. Anamaría takes the view that: “transgression like that of Eve eating the apple isn’t always borne out of a need to rebel”, instead she thinks, “it can be about curiosity and exploration”. This exploratory element manifests itself in the poems by giving the apple agency and a voice: “I didn’t like that the apple was a passive thing, I gave it a witty voice, the apple is watching Eve”. In addition, in a section inspired by Jan Van Eyck’s depiction of Eve in the Ghent Altarpiece, which Crowe Serrano saw in person, she saw the apple in the painting as the artist, the one “choreographing the scene.” Anamaría tells me she was “struck by how Eve looks ridiculously bored in Van Eyck’s painting”, that despite her being naked and tempted it wasn’t “a sensuous scene”, and how she felt that a lot of how the story of Eve and the moralistic and religious views of women “were about stripping women of their sexuality and controlling it”. This sensuous element she in part restores when writing:

Given this, and the book’s distinct use of space, colour and textual play, I asked Anamaría what she hoped readers would get from the poems contained in Crunch. She tells me candidly that she hopes that people “approach something new with an open mind” and while she knows many readers “prefer the comfort of what they know in terms of stanzas and rhyme schemes” she hopes that people also learn through experiencing a poem like this that: “understanding isn’t the be-all and end-all of reading poetry. Like a lot of modern art, it’s also about absorbing the mood, getting something out of it, and letting something wash over you like you would with a piece of music.” She thinks readers new to her work should “be prepared to be surprised” by Crunch but “to enjoy it, and take something away from it, even if it’s only a word or a phrase.”

After our conversation, I returned to the poems to think about Eve and “the fruit / in her smile / saying it all.”

Submissions are open for all HeadStuff poetry categories, including Poem of The Week (Every Friday), Unbound (longer sequence of poems from a single poet), and New Voices (submissions from poets under the age of 30.) We accept both written, audio and video recorded poems as long as the quality of the audio and video is of a high standard.

Please see our Submissions page for more information.

Photo by Holly Mindrup on Unsplash